I have been asked many times: Why ibex? Why do you travel around the world for wild sheep and goats? Here are my 10 top reasons.

1. beauty, 2. exeptional biology, 3. wildness of their habitat, 4. adventure, 5. the encouraging conservation success story of the alpine ibex, 6. people I met while researching, 7. the inscrutability of many caprinae species, 8. my personal success based on the species, 9. the lack of photos, 10. astrology – no, not really.

First encounter: It was in 1987 on a trip to Gran Paradiso National Park, Italy, when I experienced for the first time how observing an animal can actually thrill you, overwhelm you, make you think you are the happiest person on earth.

It was my first trip on my own with the intention to observe wild animals in the National Parks of Italy. I had travelled by public transport to Aosta and was waiting for a bus to get to Cogne, one of the starting points for hikers to get into the park. While I was waiting, I came to know a school class from France with its teacher. We had a nice conversation and eventually the teacher gave me a huge water melon as a farewell gift.

I love water melons, especially on hot summer days. But melons are not exactly the kind of snack you are looking for, when you plan to go hiking. Never mind! Eventually I ended up on the trail with my already huge backpack including a tripod, camera and a telelense – and a water melon, that I somehow managed to get attached on top of it.

I hadn’t really come far and was still in the valley bottom, when I realised that I had to do something against that weight. So I chose a nice spot, unpacked my melon, butchered it and started eating. I knew it was very ambitious to eat a middle-sized water melon all by myself, but what options did I have? So I began slurping slice by slice. As I mentioned before, I like water melons and the one I had was delicious, so in the beginning it was no problem. But with the first slices of the second half my stomach started to complain, but I kept going and eventually was back on the trail.

I never liked physics, but after a while on the trail I realised, that there was a case of applied physics, I had to deal with. My basic assumption had been: Get rid of the weight and thereby save energy. What I miscalculated was, that the weight reduction was not a true one, since the weight of the melon was just translocated from my back to my belly. Eventually I realised: If you don’t want to explode, you have to give up. So I chose the next nice spot between some rocks, laid down and called it a day.

After I had recovered a little bit, I took my binoculars to scan the surrounding area – still lying on my back. I detected some alpine chamois peacefully grazing on a slope and I began to like the place. After my first semester at the University of Munich I also started to feel wild and free again, here in one of the last wildernesses of Europe. I looked at my map and made plans for the following day. Light had gone from the valley bottom and I prepared to sleep between the rocks. Once again I checked the landscape for anything alive. My looks went higher and higher and eventually reached the opposite upper edge of the valley.

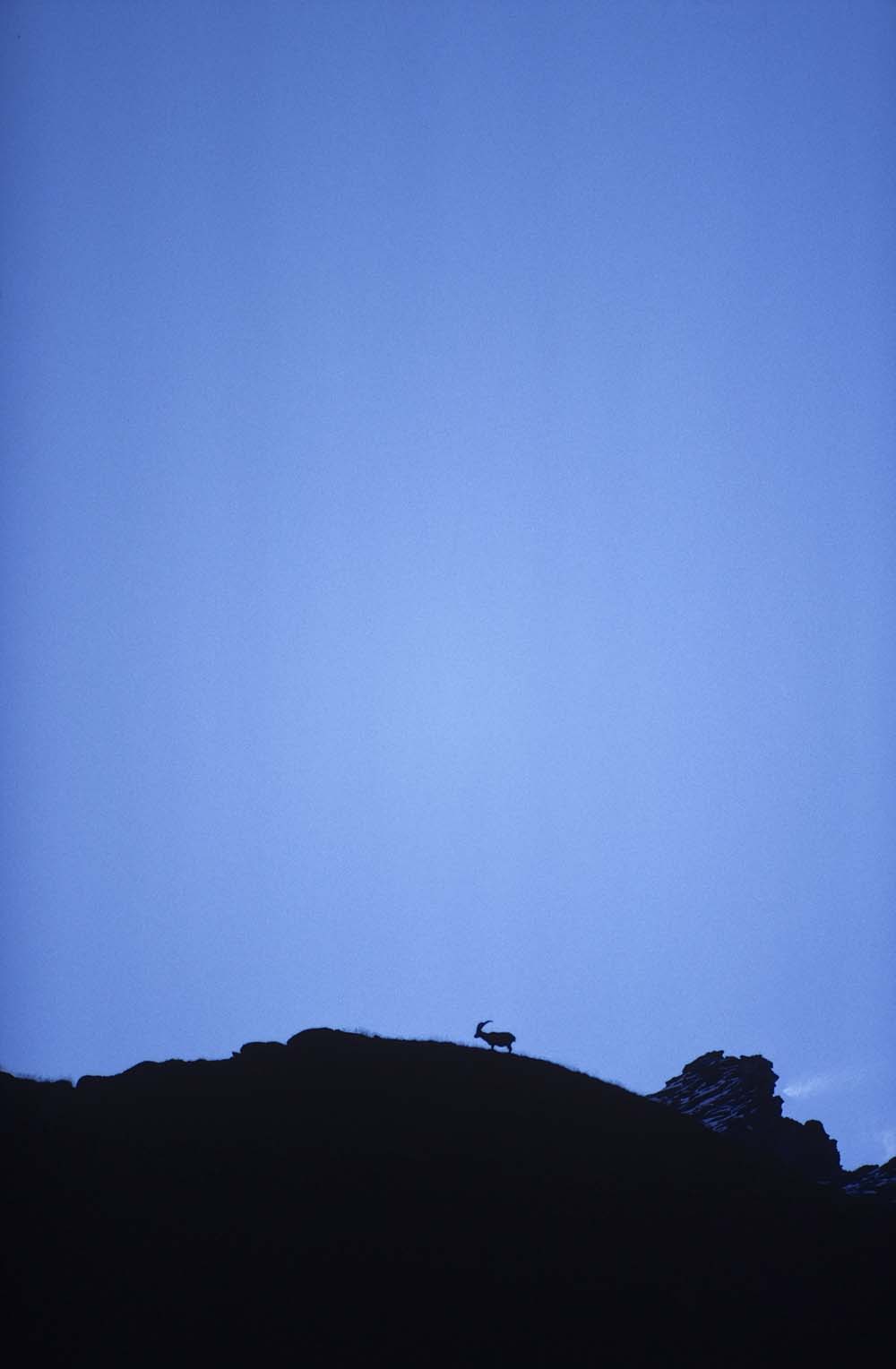

My first ibex: reason enough to become overwhelmed

And there it stood: a lone, male ibex, majestically, like a statue, contrasting the still blue sky, the first ibex of my life. I was overwhelmed and couldn’t wait to get up to him – which I did the next day and then stayed for several days to have a close look at this charismatic species.

At Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, one of my professors, Wolf Schröder, told me about an article he had made with GEO on alpine ibex. I got the edition – „Nr. 3/März 1979“. At that time Professor Schröder kept a tame ibex named Nepomuk. To demonstrate it’s climbing abilities he made it zigzagging – vertically! – through a canyon with walls, a few meters apart from each other. In a succession of eight photos the article shows how the ibex starts jumping from the left hand side of the canyon, flying across to the right hand side, thereby loosing height, using centrifugal force to cling for a split second to the vertical wall, at the same time twisting its body, then catapulting itself to the lefthand side of the canyon, again loosing hight. Then doing the same cling-twist-jump once more and finally landing at the bottom of the canyon. Within two seconds the ibex had covered several vertical meters. Phenomenal! So far I have not nearly managed to get similar photos. I guess you really need a tame animal.

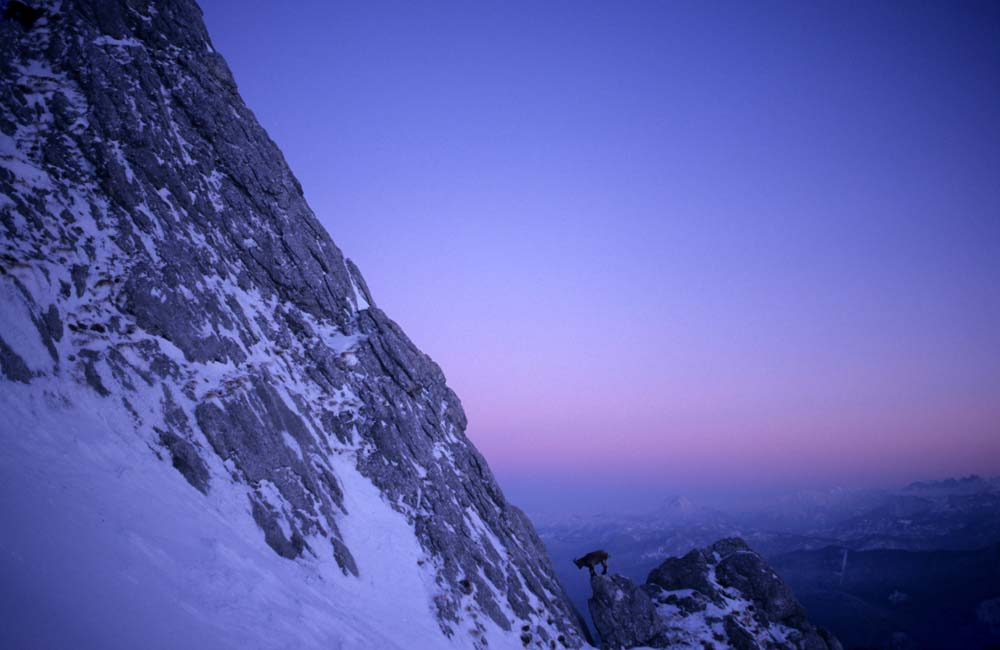

The climbing abilities of the ibex: reason enough to watch them for hours

After two semesters at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada, I travelled through the Rocky Mountains to find the „beast the color of winter“, the mountain goat, which you could call the North American counterpart to the ibex in the Alps, although the two species are not closely related.

The wildness of their habitat: another reason to deal with caprinae species, like the mountain goat in the Canadian Rocky Mountains

Again I was absolutely fascinated to experience this species – be it for its ability to survive the extremes of its harsh environment, the skill to climb the steepest cliffs or for the fact that mountain goats literally carve out sculptures while digging for mineral rich soil.

Great biology: Mountain goats become landscape sculptors while digging for minerals.

I contacted „Kosmos“, at that time one of Germany’s leading magazines for nature and wildlife – and got the job for the cover story. It was a door opener in my career as a journalist and later helped me to get in touch with the editors of GEO.

For „Kosmos“ I made the cover story on mountain goats: Today I feel like I owe these animals something.

While still researching on the mountain goats I came across Douglas H. Chadwicks’s book, the title I have already mentionend above: „A beast the color of winter“ (1983), which I still can recommend, if you were interested in mountain goats or wanted to become a wildlife biologist in the mountains. On page 31 I read about its relatives like goral, serow and takin, which I had never heard of. I checked „Grzimeks Enzyklopädie, Säugetiere, Volume 5“, released in 1988, which at that time was the only comprehensive handbook on mammals in german. Gorals and serows are given three pages. One goral species and one serow species are presented. Two photos and the relating caption are mixed up. This is 27 years ago.

Today (2016) IUCN acknowledges four goral and six serow species. What a progress in less then three decades! But even today, even reliable sources fail to visualise the species they are describing at all or correctly. There are just no photos or they are mixed up! – IUCN, arkive.org or Wikipedia are not much help.

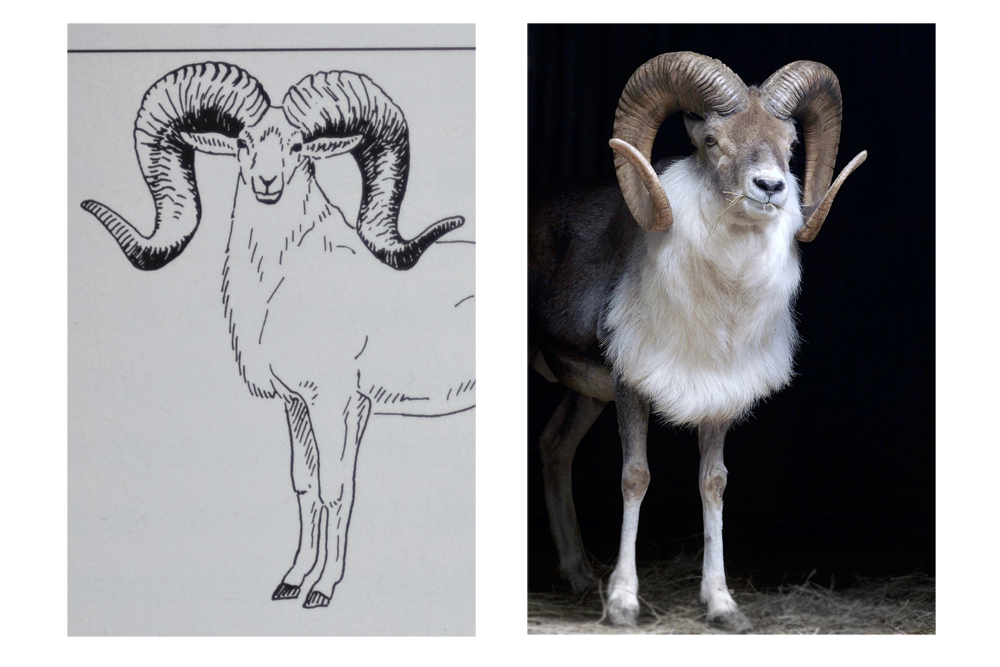

On page 550 of „Grzimeks mammals“ I stumbled across another species, that I was not familiar with: the Argali, the biggest sheep in the world. The chapter is accompanied by two paintings and one pencil sketch.

Pencil sketch of an argali as depicted in „Grzimeks Enzyklopädie – Säugetiere“ (left); photo of an argali from the Beijing Zoo (right). Note the difference in proportion regarding size in scull, horns and neck ruff. Inaccuracies like this made me want to get more into detail.

I looked at the sketch and asked myself: „Can this be true? We live in the 20. century, is this the way we have to present our fellow creatures? And besides the means of depiction, is this scetch drawn realistically? Is it possible that the diameter of a horn is bigger than the width of the coresponding scull on which the horns sit on? A photograph would have helped, but apparently at that time there was no photo of an argali available.

Impressive biology: Ibex fight for hours if they become really serious.

But before I started looking for „missing“ caprinae species, I made an article on ibex for GEO. Therefore I contacted locals in the Bavarian Alps and after a long process I got permission to use a mountain cabin close to an ibex population during the winter.

Great adventure with my friend Arni: exploring the hidden world of ibexes

Not only did I observe an ibex life and death fight for four hours and managed to find caves, where ibex die, I also had a great time in my little mountain hut, that I sometimes had to dig out of the snow, where I celebrated birthday and new year and baked the best bread ever.

Romantic life: my „ibex retreat“ in the Bavarian Alps

Romantic life II: Never mind, the dough sticking to the baking dish.

For the research of my article I also went to „Tierpark Peter and Paul“, a little animal park in St. Gallen, Switzerland, which played an important role in the conservation of the ibex: When the world population of the alpine ibex had shrunken to around 50 animals in the 19. century, it was people from St. Gallen who payed locals in Italy to steal live ibex kids from the Italian king Vittorio Emanuele II., the person in charge for the last wild roaming ibexes. The lambs that survived the smuggling tours across the Alps where then raised at „Tierpark Peter and Paul“ and eventually released in other parts of the Alps, where the new population prospered. The numbers rose within a century from 50 to over 40.000 – one of the greatest success stories in animal conservation.

Great conservation success story: Joseph Berard with ibex kids, he had stolen form the Italian king. The kids were raised in Switzerland and then reintroduced in other parts of the Alps.

At „Tierpark Peter and Paul“ I was not only welcomed by the zookeepers, Mr. and Mrs. Signer, who treated me like a lost son (I will never forget these delicious strawberries for desert!), the two also helped me to be in place, when two little ibexes were born.

Cute!: two minutes old ibex kid

Great sight: huge mixed herd of ibex and chamois in Gran Paradiso Nationalpark

And of course I had to go back to Gran Paradiso, the place, where you can observe big mixed herds of chamois and ibex numbering up to 80. And what I also definitely wanted to see was the castle of king Vittorio Emanuele II. Not only was he the guardian of the last remaining ibexes, he was also a passionate hunter. Meile et al. (2003) states that Vittorio Emanuele II and guests in his hunting parties shot 100 to 120 ibexes annually.

Home of passion: Castello di Sarre near Aosta

Many of the trophies were used to decorate the interior of the kings castle, castello di Sarre. Even if you have no use for trophies, this place is worth it for its – let’s say – architectural insanity. Or to put it in other words: At castello di Sarre you get a notion how close passion can get to ingenuity on the one side and lunacy on the other.

Ingenuity or lunacy? Hundreds of chamois and ibex trophies were used to decorate the interior of Castello di Sarre.

Even if you have no use for trophies, one has to admit how tastefully the interior architect has done his job.

With my first proper job as an editor I still kept my interest for ibex and related species. I used to get to work by train and therefore purchased season tickets, which meant that I could use the train in my spare time for free. I used it to travel all over Germany and neighbouring countries to visit zoos with caprinae species. In 2009 I started to go additionally on long-distance trips, also with the intention of documenting exotic caprinae species in their natural habitat.

Path to more adventure: We were hiking along this ridge in the Qinling Mountains of China to look for goral.

Why do I deal with caprinae species? I hope by reading the above text you get a notion: It is simply a lot of fun! Furthermore: Many caprinae species are dwindling. And most people don’t realise it. They don’t have a chance to realise it, because we don’t know these species. We sophisticated humans were so far just not interested or able to document them properly and show each other what fabulous fallow creatures we share our planet with. Certain beasts – even though they are big mammals the size of a goat – never show up in our world. Not in zoos. Not in books. Not in documentaries. Not in the world wide web. I hope my work will eventually help to narrow that gap.

At last, let me refer to point 10 of my introducing list above: I am a capricorn.

The world of the ibex is pure beauty.

The world of other caprinae species is colourful and worth to be discovered!

Literature cited

Chadwick, Douglas H., 1983: A Beast the Color of Winter – The Mountain Goat observed. Sierra Club Books

Grzimek, Bernhard (Editor), 1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie, Säugetiere, Volume 5. Kindler, München

Meile, Peter et al, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag