The „king of the goat tribe“ H. L. Haughton called the Markhor in 1913: „His very looks and bearing are regal.“ [7] For Schaller (1977) it is simply the „most distinctive goat“. [10] The vertically spiralling horns and long, shaggy hair on the front of the neck, brisket, shoulder of males are characters unique to this goat species. In fact the Markhor is the most anatomically dissimilar species of the genus Capra. And it has the greatest variation in horn configuration of all wild Capra. [7]

Names

English common names: Markhor

German: Markhor, Schraubenziege

French: Markhor

Spanish: Marjor

Russian: Винторогий козёл

Persian: مارخور Mārchor

Chinese: 捻角山羊

How the Markhor got its name

The name „Markhor“ could be a corruption of the Pashto language „mar“ = snake and „akhur“ = horn – an apt description of its serpentine horns. [1] Another meaning is snake donkey („mar“ = snake and „khar“ = donkey), hence a donkey with horns shaped like a snake. [7] Some authors believe the name to be derived from the Farsi (persian language) meaning snake eater (mar = snake; khor = eater). But no reports have been found of the animals actually eating snakes. [1]

Markhor cud foam: a remedy for snake bites

Nevertheless according to Pakistani folklore Markhor have the ability to kill snakes and eat it. Thereafter, while chewing the cud, a foam-like substance comes out of their mouth, which drops on the ground and dries. This foam-like substance is sought after and collected by locals e.g. from Gilgit Baltistan and Kohistan at the Markhor resting sites. The locals believe that the cud foam is useful in extracting snake poison from snake bitten wounds. [Explanation by Shah Zaman Gorgani from Punjab, army officer with a keen interest in wildlife – pers. comm. via facebook, 2016-10.]

Allegedly sought after by Pakistani locals for extracting snake poison: the foam-like substance that is produced while chewing cud. Photo taken at Wilhelma / Zoo Stuttgart, Germany

Taxonomy

Aegoceros (Capra) falconeri (Wagner, 1839)

Type locality: Kashmir

The genetic distance seperating Markhor from other Capra species is small. Phylogenetic analysis based on mitochondrial genome fragments reveal that Markhor and Wild Goat (C. aegagrus) belong to one clade.

Geographic variation in the horn twist and horn flare have been the principal characters used to designate subspecies. However there is no constancy in these characters within a population. [7] Hence the horn variation is overrated, which has lead to a confusing naming. [6] Today, most authors recognise three subspecies [3, 7, 5].

Subspecies

Three subspecies are recognized (Grubb 2005):

Straight-horned Markhor (C. f. megaceros (Hutton, 1842)

Flare-horned Markhor (C. f. falconeri (Wagner, 1839)

Heptner’s Markhor (C. f. heptneri, Zalkin, 1945)

The Flare-horned Markhor (C. f. falconeri) was formerly split into Astor Markhor (C. f. falconeri) and Kashmir Markhor (C. f. cashmiriensis). Schaller and Khan (1975) lumped the two.

The Straight-horned Markhor (C. f. megaceros) was formerly split into Kabul Markhor (C. f. megaceros) and Suleiman Markhor (C. f. jerdoni).

The three essential subspecies of Markhor basically defined by the shape of their horns (f.l.t.r.): Straight-horned Markhor, Flare-horned Markhor and Heptner’s Markhor. Left photo: Alain Smith (altered); centre photo: Imran Schah; right photo: Ralf Bürglin

| Name | Distribution | Other names / synonyms |

|

Heptner’s Markhor (C. f. heptneri) Zalkin, 1945

|

S Tajikistan, SE Turkmenistan, SW Uzbekistan, N Afghanistan |

– Bukhara, Bukharan or Bokharan Markhor (C. f. heptneri) – Tajik Markhor (C. f. heptneri) – Turkmen Markhor (C. f. ognevi) – Uzbek Markhor (C. f. ognevi) |

|

(C. f. falconeri) Wagner, 1839 |

NE Afghanistan, N Pakistan, and NW India |

– Astore or Astor Markhor (C. f. falconeri) – Gilgit Markhor – Hazara Markhor – Kashmir Markhor (C. f cashmiriensis) – Pir Panjal-Markhor (C. f cashmiriensis) – Kaj-i-nag Markhor (C. f cashmiriensis) |

| Straight-horned Markhor (C. f. megaceros) Hutton, 1842 | WC Pakistan, E Afghanistan |

– Kabul-Markhor (C. f. megaceros) – Suleiman or Sulaiman Markhor (C. f. jerdoni) |

Goat or Markhor?

Lydekker also included the Chiltan Wild Goat, which he thought to be already extinct, under Markhor as C. f. chialtanensis, subsp. nov. Contrary to Lydekker’s assumption, the Chiltan Wild Goat was not extinct and was reclassified by Schaller and Khan (1975) and Schaller (1980) as C. aegagrus chialtanensis. [1]

Should the dumped subspecies still be taken into account?

Damm and Franco (2014) make a very interesting point by indicating that conservation and sustainable use options for five phenotypes – Heptner’s, Astore, Kashmir, Kabul and Suleiman – differ within the local socioeconomic context, but also that the core distribution ranges of the five types are now completely separated. They believe that best-possible Markhor conservation outcomes are conditional on this split. On the other hand they emphasize, that in principle they agree with Schaller’s cited arguments; the individual description of the five phenotypes in terms of pelage and horn geometry remains fraught with difficulty. [1]

Distribution

by country/state: Afghanistan (northeastern), India (southwest Jammu and Kashmir), Pakistan (northern and central ), Tajikistan (southern), Turkmenistan (southwestern ), Uzbekistan (southern) – (Grubb 2005). [5]

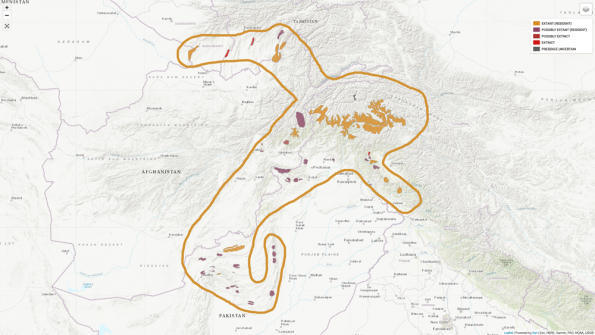

The entire historic distribution range has roughly the form of the lower case letter „t“ [1] – with the vertical axis starting around Quetta in the South running in a roughly north-easterly direction all the way into the Karakoram Range. The horizontal axis runs from Turkmenistan’s Kugitang Mountains in the Northwest to India’s Pir Panjal Range in the East. The bend at the lower part of the „t“ follows down the Sulaiman Range, turns west towards Quetta and than north.

The Markhor distribution range-„t“. Explanation: see text above. Source: IUCN red list distribution map for Markhor (altered)

Today most of the remaining Markhor populations of the Straight-horned and Flare-horned subspecies roam the mountains in Pakistan. Population numbers in the neighboring range countries (Afghanistan, India) are far lower. The range states for the Heptner’s Markhor are Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, with Tajikistan having by far the largest populations. [1] Bordering Tajikistan, there is also a small subpopulation in in the Darwaz region, in the north of Afghanistan. [8]

Distribution by phenotypes [1]

Astore Markhor: endemic to Gilgit-Baltistan Province, Pakistan

Kashmir Markhor: Pir Panjal Ranges and Kaj-i-nag Ranges in Indias Jammu and Kashmir State; crosses Pakistan in the North through Azad Kashmir and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa Provinces; reaches into Hindu Kush in the Afghan provinces of Kunar and Nuristan.

Kabul Markhor: in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA); Murghazar Hills, Khanori Hills, the Sakra Range in the northeast of Mardan, the Safed Koh (Spin Ghar) Range / upper Kurram Valley, and in the Kohi Safi region / Afghan Parwan Province.

Suleiman Markhor: relatively widespread in the mountain complexes of west-central Pakistan; Suleiman Coniferous Forest (aka Suleiman Chilgoza Pine Forest) north of Zhob; on all major mountain ranges around Quetta; greatest concentration: in Pashtun tribal areas within Qilla Saifullah District – presumably extending into Afghanistan (Paktika and Zabol).

Heptner’s Markhor: in two segregated population units – 1: Southeastern Tajikistan and adjacent parts of Badakhshan Province in Afghanistan; 2: Kugitang Mountains on the border of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan

For a detailed description of the subspecies range, see the respective chapters.

General description

Sizes, ruffs, horns: the Markhor cline

Schaller (1977) writes: „The Markhor in Pakistan represent a cline: The smallest animals with the shortest ruffs and straightest and most twisted horns are in the south, and the largest ones with the longest ruffs and most flaring and open-spiralling horns are in the north. Intermediate forms exist, which is not surprising since the ranges of some forms, such as the Kabul and Kashmir Markhor, almost touch. Local populations are often isolated, and it ist therefore surprising not that variation exists but that there is so little of it.“ [10]

length / head-body: 155-170 cm (males) [3]

shoulder height: 65-104 cm [3]; average around 90 cm [1]; with an increase in size from south to north [6]; the Flare-horned Markhor includes the largest specimens. Straight-horned Markhor from arid southern Pakistan are smaller. [7]

tail length: 10-20 cm [3]; dark, not as bushy as that of ibexes [7]

weight: males 80-108 kg [3] / 70 – 110 kg [1]; 32-50 kg (females) [3, 1] Flare-horned Markhor includes the heaviest specimens. [7]

horn length: 80-165 cm (males); 35 cm – rarely longer in females [3]

horn basal circumference: 15-34 cm (males) [3]

beard: long and dark, continuous with the lighter hair of the cheeks; most females also have one [3]; only females of southern Balochistan are often without beard. [1]

life expectancy in the wild: up to 12-13 years [5]; rarely more than 12 years (males) [3]; 11-13 years [1]

diploid chromosome number: 58 [1], 60 [3] – contradicting!

Colouration / pelage

General body color is reddish-gray, but with more yellow-buff tones in the summer coat of both genders and more gray in the winter coat. In males, a darker crest of longer hair extends from the withers down the spine. Long, white or gray shaggy hair develops on older males on the front of the neck, brisket, shoulder, upper part of the forelegs, and upper front of hindlegs. The long hair on the sides of the cheeks is continuous with the long, dark hair that forms the beard. The legs and belly are creamy, except for the front of the shanks, which are darker. A callosity surrounded by white hairs on the „knee“ breaks the dark pattern on the front legs. The rump patch is small and whitish. [7]

The black beard is extremely long. It is is continuous with the long hair on the sides of the cheeks and the neck (Heptner’s Markhor). On the front of the „knee“ there is a lighter carpal patch or callosity. [1] Photo taken at Wilhelma / Zoo Stuttgart, Germany

Females have beards too (Heptner’s Markhor). But it is said that females of southern Balochistan are often without beard. [1]

The small, white rump patch descends down the upper legs. The tail, which is naked on the ventral surface, is short and sparsely covered with long black hairs. [1] Photo taken at Zoo Augsburg, Germany

Dorsal stripe: In general both sexes have a darkish mid-dorsal stripe extending from the shoulder to the base of the tail. However Kashmir Markhor have been documented with a whitish dorsal stribe. [1]

Narrow, dark dorsal stripe in a female Heptner’s Markhor. Photo taken at Wilhelma / Zoo Stuttgart, Germany

Black-and-white markings on the metacarpi of a 3,5 year old male Heptner’s Markhor. Photo taken at Tierpark Berlin

belly: creamy white [1]

Horns

There is great variation in the horn flare and the tightness of the horn twist. Actually Markhor have the most diverse horns of all wild Capra. [3] The horns are highly sexually dimorphic. [1]

Horns of rams are corkscrew-like and massive, with the frontal keel always twisting outward and spiraling upward in a heteronymous twist (the left horn forms a right-hand spiral and the right horn a left-handed one). The horns are closely approximate at the base, laterally compressed and show distinct keels (front and back), both of which twist around the axis of the horn. [1]

Females horns are short (rarely exceed 36 cm). [7] Horns of females of the northern races usually have horns with one-and-a-quarter twists near the tip, diverging outwards. Females of the southern populations have horns with only one twist. [1]

Varieties of the open-spiraled horn type can be found in any one locality. That means: In areas where a certain horn type is typical, also expect to find the „wrong“ type of spiral. Then again certain horn types/subspecies can be „overwhelmingly separated“. [4]

The extreme horn forms are the open spiral, out-flaring Astore type horns usually with one-and-a-half twists to the spiral, where the horn axes lie in the centre of the open space between the twists, and the tightly twisted (up to 4 turns!), straight horns of the Suleiman type, where the horn axes go through the centre of the horn in its entire length.

Straight-horned Markhor (C. f. megaceros): Horns are spear- [6] or screw-like and V-shaped – straight with a very tight spiral (two ore more complete spirals) – some almost reminding of a narwhal tusk. These horns rarely exceed 91 cm. [7]

Flare-horned Markhor (C. f. falconeri): Horns are lyre-shaped [6] or Y-shaped. First both horns go straight up, standing closely toghether for a short length, then they flare. The spiral is open, the tips highly divergent. The horns of the Flare-horned Markhor exhibit the greatest means in horn length, basal circumference, and tip to tip spread (133 cm). [7]

Heptner’s Markhor (C. f. heptneri): Horns are corkscrew-like [7] and V-shaped [6]. The spiral is of an intermediate type: „tight“ compared to Flare-horned Markhor, „open“ compared to Straight-horned Markhor. They flare with the tips highly divergent [3], but less then the Flare-horned Markhor.

Typical for Markhor: The insertion at the horn base is not in one plane – highlighted here through white line and arrow.

The horn of Markhors usually grow lifelong – like in all Bovidae species. But horns can accidentally break off.

The listings of Markhor trophies in the Rowland Ward and SCI databases are problematic to interpret. Separating the entries according to the phenotype categories and distribution ranges would be fraught with difficulty and would not serve any purpose, especially since most of the larger trophies have been taken many decades, if not more than hundred years ago. Furthermore, some of the older entries in Rowland Ward had the horn measured in a straight line instead of the newer method of measuring length around the spiral. Significantly, several authors noted already in the early 1900s that excellent heads had become scarce, with over-hunting by British civil and military sportsmen cited as the main cause. [1]

Table 1: Horn measurements in the different Markhor phenotypes

| horn length (cm) | basal circum-ference (cm) | tip-to-tip-spread (cm) | harvest date | |

| Kashmir [1] | 165 | 33,7 (mean: 27,9) | 62,2 cm to 120,7; median: 87,9 (n=35) | second part of the 19th and early 20th centuries |

| 158, 8 | 1984 | |||

| Astore [1] | 154,3 | 35,6; mean: 27,9 (n=48) | 44,5 cm to 132,1; median: 91,4 (n=39) | harvested more than a century ago |

| Kabul [1] | probably > 110 | 96,5 | past | |

| 99,7; median: 77,2) | more recently | |||

| Suleiman [1](or Kabul) | 133 | 25,7 | 49,5 | 1969 |

| 111,8 | 23,2 | 1968 | ||

| Heptner’s [1] | 108 | 25,1 | 48,9 | 2000, Uzbekistan |

| [4b] | 124 | 2016, Tajikistan |

Habitat

Capra falconeri is adapted to mountainous terrain with steep cliffs, between 600 and 3.600 m elevation. [5] In northern areas of its range it occurs at higher elevations. [3] Markhor rarely use the high mountain zone above the tree line. [5]

The species is typically found in areas with open woodlands, scrublands and light forests. [5] But they tolerate diverse vegetation types: in the southern ranges, as well as those along the upper Indus, Markhor inhabit arid, desolate hills, almost devoid of trees, whereas many of those in Chitral frequent stands of fir and paths of evergrean oak, and still others, those in Pir Panjal, may be found in dense pine and birch forests. [1]

Temperatures in Markhor habitat may vary from 45°C or more in the southern ranges, down to -15°C in the northern mountains. Tough Markhor seem to prefer fairly dry habitats, with an average annual rainfall of 100 cm or less.

Habitat preference by sexes: Females use open, steeper resting sites than males. In Turkmenistan, adult males occured at elevations higher than 1800 m and females generally occured below 1800 m in large rugged canyons. [3]

In Pakistan and India the habitat vegetation is made up primarily of oaks (e.g. Quercus ilex), pines (e.g. Pinus gerardiana), junipers (e.g. Juniperus macropoda) and Deodar Cedar (Cedrus deodora) as well as spruce (Picea smithiana) and fir (Abies spectabilis, A. pindrow) in certain areas. [5]

In Tajikistan the vegetation in the lower parts consists of open woodland and shrub communities with Pistachio (Pistacia vera), Redbud (Cercis griffithii) and Almond (Amygdalus bucharica); with increasing elevation juniper trees (Juniperus seravschanica), (J. semiglobosa), mixed with shrubs of maple (Acer regelii, A. turkestanicum), rose (Rosa kokanica), honeysuckle (Lonicera nummulariifolia) and Cotoneaster spp. [5]

Markhor have several habitat requirements:

- presence of cliffs into which to retreat in case of danger

- absence of deep snow

- suitable terrain below an altitude of about 2.200 m, where temperatures are moderate in winter

These requirements lead to seasonal altitudinal migrations. [1]

Where Markohr and Asiatic Ibex share the same area, Markhor usually stay at lower elevation [pers. observation, Darwaz region, Tajikistan]

Mortality / Predators

Predators include Wolf (Canis lupus), Snow Leopard (Panthera uncia), Lynx (Lynx lynx). Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) prey on kinds. [5] Wolves and Snow Leopards are the major predators. [3]

Food and feeding

Markhors eat equal proportions of grases and forbs (26 per cent each) and 48 per cent browse. They prefer grases and forbs in summer and browse in winter. In northern Pakistan, oak leaves constituted 88 per cent of their winter food. They also actively seek oak acorns. In Tajikistan, adult females consumed 7-11 kg and kids 2,4-4 kg of forage per day. Markhor actively climb trees to browse on leaves and twigs during winter (see also „Funky Biology“). In some regions, trees are not a major habitat component. Instead they spend considerable time feeding on steep slopes and cliffs. [3]

Leaves can constitute up to 88 per cent of Markhor’s winter food. Photo taken at Wilhelma / Zoo Stuttgart, Germany

The chipmunks amongst wild goats

In one puplished obervation, 27 out of a group of 40 Markhors were feeding in trees. Females in northern Pakistan spent 37 per cent of their total feeding time foraging in trees, usually at a hight of 1-5 m, but up to 9 m. They are agile climbers, capable of jumping from limb to limb. Males older than three years of age do not climb trees because of their weight and the hinderance of their horns. Instead they feed on the ground, benefitting from others, which are foraging above in the trees and let things fall down. [3]

Breeding

sexual maturity reached: at 18-30 months [5]; females at age 2-3 [3]; female Straight-horned: 30-36 months (Roberts, 1977); Flare-horned: 24 month (Aleem and Malik, 1977) [1]; older males do most of the mating. [3]

mating: mid-December to early January (northern Pakistan); in southern megaceros-populations in October-November. [3]

gestation: 165-175 days [3]; 160-170 days [1]; 135-170 days [5]

parturition: from late April to early June [3]

young per birth: typically 1-2 kids [5]; 1 most common in females younger than five years; twins are common in older females [1]

Flehming Heptner’s Markhor male. Photo taken at Zoo Augsburg

Activity patterns

In undisturbed habitat markhor are largely dirurnal. [1] Moving and feeding are most common in the morning and late afternoon. Resting is common at noon and early afternoon. [3] In winter they feed intermittently throughout the day. [1] Markhors prefer southern slopes in summer and winter. During winter, at midday, after valley bottoms warm, Markhors descend and forage on the slopes until after dark. [3]

Movements, home range and social organisation

Markhors move around considerably during the course of a year. Distance between winter and summer range can be 10-15 km. Total annual range is 80 km². In northern Pakistan, in a population of about 100 Markhors 31 per cent were adult females, 8,5 per cent yearling females, 40 per cent young, and 20,5 per cent males. Of the males 7,9 per cent were yearlings, 2,4 per cent were 2,5 years old, 4,2 per cent were 3,5 years old, and 6,1 per cent 4,5 years old or older. The sex ratio was about 1 male: 2 females. Female herds consisted of 2-18 individuals, with a mean of nine. In Tajikistan, in a population of about 50 Markhors, 26 per cent were adult females, 40 per cent were kids, 24 per cent were yearlings, and 10 per cent were adult males. In a strictly controlled hunted population in west-central Pakistan, 14 per cent of males were six or more years old. [3]

Conservation Status

According to IUCN this species is assessed as „near threatened“: it nearly qualifies as Vulnerable under criterion C2a(i) as there are less than 10.000 mature individuals (estimated 5.808, based on data from 2011-2013) and each subpopulation, except one, has less than 1.000 mature individuals. The largest subpopulation had an estimated 1.697 mature individuals in 2011. There is no observed, estimated, projected or inferred continuing decline of the total population. However, stable and increasing subpopulations are restricted to areas with sustainable hunting management and protected areas. Were these conservation activities to cease in the future, poaching would likely increase, possibly changing positive trajectories in these areas downward, and the species would then qualify as Vulnerable. [5]

The previous (2008) assessment of Endangered appears erroneous. The data available would have qualified the taxon for the category Vulnerable based on criterion C with <10.000 mature individuals, because the most recent estimates cited by Valdez (2008) ranged from 5.080 to 5.630 (mean 5.355) individuals, of which 60% or 3.213 would have been mature animals. Further, there had been an inferred continuous decline (C1), and in the largest subpopulation in the Torghar Hills there were an estimated 1.600 individuals, of which 960 (60%) would be assumed to be mature, just meeting the threshold of criterion C2a(i) for the category Vulnerable. [5]

The reason for the change from category Vulnerable (the corrected 2008 assessment) to Near Threatened is genuine (recent, since assessments 1994, 1996 and 2008). Available data show that the earlier population decline had ceased for more than five years due to effective conservation measures. This has led to the stabilization of key subpopulations and increase in parts of the species range. Since 2002, the largest subpopulation has been estimated at >1,000 mature individuals for a number of years. Thus, criteria C1 and C2a(i) for Vulnerable have not been met for five or more years. [5]

Threats

Within Afghanistan, Markhor have traditionally been hunted in Nuristan and Laghman, and this may have intensified during the Afghan wars since 1979. According to surveys by WCS in Nuristan during 2006-2007 and 2008 (WCS 2008), Markhor continue to be the most important game for local hunters (despite a nominal nationwide ban on hunting). Petocz and Larsson (1977) wrote that rangelands and forests were likely capable of supporting a higher Markhor population than that observed. They assumed that impact of livestock grazing on habitat conditions was limited because the number of domestic animals was restricted by the area’s capacity to produce and store winter fodder, as heavy snowfall prevents winter grazing. Recent numbers of livestock are unknown for Nuristan, but recent increases associated with an expanding human population may create competition for forage (WCS 2008). According to a study using recent satellite imagery (Delattre and Rahmani 2007) no large-scale deforestation of the coniferous forests was observed in Markhor habitat in Afghanistan. However, the extent of deforestation for the last five years in a region affected by war and largely out of state control is unknown. [5]

In India, all Markhor populations are small (usually < 50) and fragmented. The largest population, in Kajinag, may have potential for long-term survival if immediate conservation measures can be implemented. Key threats to the Markhor’s range are insurgency-related effects, intensified local resource use, poaching, and large-scale development. Poaching by professional hunters may have been the primary cause of decimation of Markhor in the past, but communal hunting during winter was practised until recently. Armed conflicts may have increased poaching by both the military and militants, while poaching by local people may have declined due to confiscation of arms and restriction on human movements. Other pressures come from habitat encroachment by camps of Gujjars and the armed forces, excessive livestock grazing by local and nomadic Bakkarwal herders in parts of the range, and collection of timber and other forest products. Large scale development includes the proposed Mughal road connecting the state capital Srinagar with Rajouri, which passes through the Hirpura Wildlife Sanctuary, and limestone and gypsum mining around Limbar and Lacchipora Wildlife Sanctuaries. The Indian Government has fenced the entire Line of Control with multi-layered barbed wire. This may have caused further fragmentation of populations of Markhor (Bhatnagar et al. 2009). [5]

In Pakistan, control of poaching in Chitral Gol National Park and in several community-based conservancies has been successful. There, the population is stable or increasing. However, many subpopulations of Flare-horned Markhor are still small (< 100) and the level of connectivity between them is unknown. The major threat outside established conservancies is poaching. [5]

Trophy hunting Markhor

Pakistan and Tajikistan are the only range states where local communities have successfully been involved in Markhor conservation/trophy hunting. [1] In Pakistan this has generated more than US $ 2 million for community development. Markhors are protected by local game wardens paid by funds generated through sport-hunting programs; populations are periodically monitored and have increased. Of the trophy fee charged per Markhor, 20 % goes to the government and 80 % to the local community. [3] In 2013 the trophy price for Markhor has reached about US $ 80.000-100.000. [5]

Tajikistan started its community based trophy hunting program in late 2013. [1]

Areas with community-controlled, sustainable Markhor hunting: [1]

Astore Markhor (Flare-horned Markhor)

– Skoyo-Karabathang-Basingo (SKB) in Skardu Conservancy

– Hushey CCHA and the Shahi Khyber Imamabad Welfare Organization (SKIWO)

– Bunji Community Conservation Area (BCCA), Diamir District

– Dashkin-Mushkin-Turbiling (DMT)

Kashmir Markhor (Flare-horned Markhor) – areas open or under planning process

– Tooshi-Shasha Conservancy (Chitral)

– Gehrait-Goleen Conservancy (Chitral)

– Mankial Valley Conservancy (Swat)

– Kaigah Nullah Conservancy (Kohistan)

Suleiman Markhor (Straight-horned Markhor )

– Torghar Conservation Project (TCP), Torghar Hills

– Takatu Conservation Area, Quetta and Pishin districts

Heptner’s Markhor – only in Tajikistan

– Markhor conservancy near Sarichashma

– Muhofiz conservancy near Khirmanjo

– M-Sayod near Zighar

Best example of best practices of sustainable use

Robert Hepworth, executive secretary of the United Nations Environment Program – Convention on Migratory Species (UNEP CMS) Secretariat, said at the first CIC Markhor Award presentation in Bonn in 2008 that: „…the Convention on Biological Diversity refers to the Torghar project [for the conservation of Markhor and Afghan Urial through hunting] in Pakistan as the single best example of best practices of sustainable use.“ [1]

In India, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan Markhor may not be hunted legally.

How to hunt Markhor: In individual populations of polygamous species such as the Markhor, the removal of too many large prime-age males through trophy hunting can have an effect on the herd’s reproductive capacity and a long-term genetic effect. Hence, Markhor conservation strategies should dictate that the trophy-hunting harvest does not exceed 2 per cent of the total male population of a given area to safeguard both long-term population viability and genetic diversity. Horn length should not be the only criterion for the hunter. Selection on horn length alone increases the danger of the removal of disproportionate numbers of fast-growing and genetically superior males at a relatively young age. Younger large-horned males should be given the chance to spend a couple of years at the top of the breeding hierarchy. [1]

Markhor and Snow Leopard: If community-based trophy hunting programs are just tailored to preserve single ungulate species, rather than entire ecosystems, these programs bear the risk that incentives gained through trophy-hunting may be worsening human-carnivore conflicts. Attitudes of the communities towards snow leopards – and wolf – may become negative. On the other hand, increasing mountain ungulate populations lead naturally to an increase in predator populations. [1]

In the last years numbers of Markhor have risen through sustainable trophy hunting programs. Photo taken at Zoo Augsburg

Ecotourism

In Tajikistan the Association of Nature Conservation Organizations of Tajikistan (ANCOT) offers tours to watch Markhor in the Darwaz region. However as of 2020-02 the income for locals through wildlife watching compared to hunting is neglectable (Khalil Karimov, pers. comm.).

In Pakistan www.terichmirtravel.com reportedly also offers tours.

Only a few people dare to venture independently to the realms of the Markhor. Accordingly trip reports are rare: Alain Guillemont went to Kashmir – see his trip report. Jon Hall went to Thushi reserve/Pakistan for the purpose of seeing Markhor in the wild – trip report. Ralf Bürglin went to the Darwaz region of Tajikistan in 2020 – trip report.

For most of the Markhor’s range safety is a big concern – and it already was, when Stockley (1936) travelled the area: „My last four trips have had to be carried out with an escort of forty rifles.“ [11]

Literature Cited

[1] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

[2] Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.),1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

[3] Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

[4b] Jagen Weltweit 2016-02-03: Tadschikistan – Weltrekord Buchara Markhor von österreichischem Jäger erlegt: https://jww.de/tadschikistan-weltrekord-buchara-markhor-von-oesterreichischem-jaeger-erlegt-2829/. Downloaded:2020-05-11.

[5] Michel, S. & Rosen Michel, T. 2015. Capra falconeri (errata version published in 2016). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T3787A97218336. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T3787A82028427.en. Downloaded on 06 May 2020.

[6] Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern

[7] Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the Pinnacles – Wild Goats of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.

[8] Moheb, Zalmai et al., 2018: Markhor and Siberian ibex occurrence and conservation in northern Afghanistan. Caprinae News 2018 (1)

[10] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain Monarchs – wild sheep and goats of the Himalaya. The University of Chicago Press

[11] Stockley, C., 1936: Stalking in the Himalayas and Northern India. London: Herbert Jenkins.