The Mishmi Takin is one of four subspecies of Budorcas – the „ox-gazelle“. The species name taxicolor refers to the coat colour of the American Badger (Taxidea taxus). The type specimen was collected in the Mishmi Hills of India.

Names

Burmese: Tha Min [2]

Chinese: gāo lí gàng; gòng líng niú [2]

English: Mishmi Takin [2]

French: Takin de Mishmi [2]

German: Mishmi Takin [2]

Russian: Бирманский такин [Wikipedia]

Spanish: Mishmi Takin [2]

Tibetan: Ri-ka, Ye-more, Shing-Na [2]

Taxonomy

Budorcas taxicolor Hodgson, 1850, Mishmi Hills, East Himalayas [16]

diploid chromosome number: 42 [16], 52 [2] – contradicting!

Similar species / subspecies

The Mishmi Takin is similar to the Bhutan Takin. Their range boundaries are not clear. From the northerly subspecies – Sichuan and Golden Takin – it can be differentiated by its darker pelage.

Distribution

by country and state: Northeast India (Mishmi Hills, Arunachal Pradesh); South China (South Xizang [Tibet], Northwest Yunnan); northern Myanmar [16]

The Mishmi Hills in India is the region that gave the Mishmi Takin its name. (Editor’s note: The name „Hills“ is misleading. The Mishmi Hills are a southward extension of the Himalayas with an average elevation of 4.500 metres. [2] The „hills“ are actually mountains.) Further southeast along the border with China and Myanmar, as far as Namdapha National Park, the subspecies prevails as well in this country.

In China it occurs south of Medog County at the lower branch of the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River on the mountain slopes on the border with Arunachal Pradesh (India). In northern Yunnan Province, Mishmi Takin inhabit the Gaoligong Shan. These mountains are between the west side of the Salween (Nujiang) River and the Sino Myanmar border. This eastern section of its distribution range extends south from around Gongshan Derung and Nu Autonomous County, to include Fugong, Lushui, Tenchong, Baoshan, and at least as far as Longling (Feng et al. 1986, Wu et al. 1987). [2]

In Myanmar Mishmi Takin occupy the high mountain slopes above 2.800 metres in Kachin State in the north of the country at the border with China (Blower 1985, Salter 1997). This area is north of Putao (the northernmost town of Kachin State) and west of the Ayeyarwady-Salween divide (Cuffe 1914, Hla Aung 1967). The Mishmi Takin is common in the mountain forests of the Hkhakabo-Razi Protected Area (Rabinowitz et al. 1998). [2] ((editor’s note: still is?))

The great bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) River is thought to delineate the western boundary of the Mishmi Takin’s range in Xizang (Tibet). [2] But if the Brahmaputra in India can be seen as the southern extension of that boundary is questionable. East of the Brahmaputra are the Mishmi Hills, and it is here and in adjacent areas, where the geographic ranges of Mishmi and Bhutan Takin meet. Overlap and intergradation is thought to occur. [2]

Description

general appearance: Takins in general have large, bovine-like bodies, a shaggy coat including long hair on the side and under the jaws, stout legs, prominent dew claws, and are taller at the shoulder than the hip. [16]

According to other Mishmi Takin accounts, descriptions of the body size are not consistent: Damm and Franco (2014) write that body size of the Mishmi Takin is approximate to the Sichuan Takin but larger than bedfordi and taxicolor subspecies.“ [2] ((Editor’s note: There is no quote for this statement, which would have been important, because other authors make different statements – see below. And „taxicolor“ must be a misspelling since this name refers to the Mishmi Takin. The authors probably meant whitei)).

Matschei, Christian (2012) writes that the Mishmi Takin is smaller than Sichuan and Golden. Castelló (2016) notes that Mishmi is similar to Bhutan, but smaller than Sichuan and Golden. Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) do not see any differences in body sizes. The following measurements are theirs and probably refer to Takins in general [16]:

body length: 170-220 cm – males are significantly larger than females [16]

shoulder height: 107-140 cm; [16]

weight: 150-350 kg [16]

tail: 10-22 cm [16]

longevity: 16-18 years but mortality in wild populations is unknown. [16]

Colouration / pelage

Accounts on pelage colour are likewise not consistent. None of the authors mentioned here distinguishes between sexes, summer or winter coats. Inconsistencies could also be attributed to regional differences. Damm and Franco (2014) write: Herds appear to vary in colour, more reddish in one district and more brownish in another a few miles distant. [2] ((citation needed!))

Damm and Franco (2014) note that the Mishmi Takin’s coat is dark brownish or reddish brown suffused with grayish-yellow, apparently somewhat lighter than the pelage of Bhutan Takin. The body colour tends to be of lighter tones, whereas extremities including head, neck, tail and legs are dark, almost black. [2]

Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) write that the upper body parts of mature Mishmi Takins are pale yellow, with a brindled (german: gestromt / gestreift) area between the upper body and the lower dark areas. Lower flanks, haunches (german: Gesäß), belly, legs, lower neck, and entire face are black. [16]

Mishmi Takin male in summer coat. Saddle and esxpecially upper neck are bright orange. Photo: Richard C. Dowers / Paignton-Zoo / 2017-8-28

7-year-old male in winter coat (November). With this specimen one can comprehend why the species name taxicolor was choosen. It refers to the pepper-and-salt coloured coat of the American Badger (Taxidea taxus). The yellowish hairs are still remains from the summer coat. Photo: Bürglin / Tierpark Hellabrunn, Munich

14-year-old Mishmi Takin female in November. Note the almost uniform brown body without lighter-coloured saddle, converging horns, relatively large gap between horns. Photo: Bürglin / Tierpark Hellabrunn, Munich

According to ISIS the Mishmi Takin is a widespread subspecies in zoos around the world (2017: 68 institutions). All animals are descendants of wild animals caught in Myanmar – and not the Mishmi Hills, India (ISIS, pers. comm.). A high percentage of these animals has reddish haunches and hindlegs. 7-year-old male. Photo: Bürglin / Tierpark Hellabrunn, Munich

Mishmi Takin female from the Mishmi Hills near Mayodia Pass. Note the entirely black head, extensive light area over the back; hind leg shows no red. Photo: Bürglin / Mishmi Hills, 2017-10-27

Sex determination in Mishmi Takins is sometimes challenging. Note the extensive bright area over the back, light forehead, massive horns without gap, but with converging horn tips. Photo: Bürglin / Mishmi Hills, 2017-10-27

Juveniles, up to about 6 months of age: light brown; black extends with age. [4] Young calves are rather dark in colouration. [2] These descriptions seem to contradict, but they make sense, when you look at the following photographs:

When you compare this photo of a young with the photo of a mature male below, you see that the overall tone is „darker“, but the dark parts, especially the haunches are lighter (brownish instead of black). Juvenile Mishmi Takin from Chomutov in February. Photo: Bürglin

… accordingly in this male the lighter parts – saddle, upper neck, forhead – are lighter than in the juvenile. And the darker parts – haunches, legs, muzzle – are „darker“ (black instead of brown). Male from Chomutov in February. Photo: Bürglin

Mishmi Takin female and young in the Mishmi Hills. Besides the size the pelage colour pattern could be an identification hint for age classes. Note the young on the right side is darker compared to the leading mother. Photo: Bürglin

dorsal stripe: dark; may be apparent; hairs on each side of the dorsal stripe are quite light coloured, contrasting sharply with the darkish hair further down the flanks and haunches. [2]

Mishmi Takin female from Mishmi Hills. Note the dark dorsal line, extensive light area over the back; relatively massive, but converging horns. Photo: Bürglin / Mishmi Hills, 2017-10-27

ventral surfaces: usually darker than dorsal surfaces [2]

Forehead: The area below the horns may be of lighter colour shades, but there are specimens with an entirely black face too [2]; 7-year-old male in November. Photo: Bürglin / Hellabrunn

Rump: The tail in this specimen is accentuated by a light, heart-shaped rump patch. 14-year-old female at the end of November. Photo: Bürglin / Hellabrunn

Horns

As in all Takin subspecies horns grow slightly upward, and then turn outward and backward with the horn tips upward.

Males have larger horns than females. Male horn measurements are similar to those of the Sichuan Takin. [16]

In Mishmi Takin males horn tips often diverge. Note the protruding horn base. 7-year-old in November. Photo: Bürglin / Hellabrunn

In Mishmi Takin females horn tips often converge. Note the comparatively larger gap between horns. 14-year-old in November. Photo: Bürglin / Hellabrunn

For Damm and Franco (2014) it looks like the horns of Mishmi Takins are generally larger and more massive than those of the Bhutan Takin: Rowland Ward (2006) has only 18 historic entries (1891 and 1934) for this subspecies. A trophy from 1902 measures 63,5 cm in length and the horn has a circumference at base of 33 cm. The median horn length is 54,9 cm. All heads have also been measured for tip-to-tip spread and these measurements indicate a fairly equal spread of ca. 30,3 cm. (Due to small sample size no assessment can be made for Sichuan and Golden Takin.) [2]

Habitat

This species is found in eastern Himalayan pine shrub, subtropical forest, and possibly temperate forest in Myanmar (Than Zaw pers. comm. 2006). [14]

Mishmi Takins occur at elevations of 1.200 to 3.000 metres but may occupy higher elevations in the summer to reach alpine meadows. They also inhabit mixed coniferous and broad-leafed deciduous forests where forage can be seasonally more available. They also often occur in steep, densely vegetated areas where they may be difficult to see. They are most vulnerable to human disturbance at lower elevations, although livestock grazing is practiced at all elevations where they occur [16]. On the other hand Takins in the Mishmi Hills also use old growth forests, where livestock is not a critical factor (own observation).

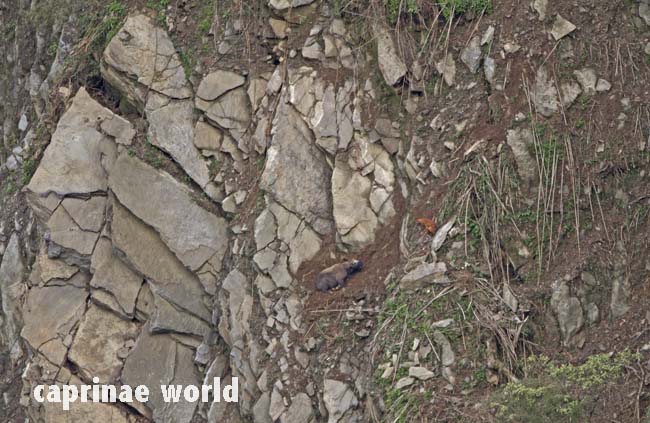

Six Mishmi Takins at a steep, forested hillside at 2100 metres asl at the end of October. Photo: Bürglin

In this landslide area below Mayodia Pass, Mishmi Hills, Takins have been seen during the winter. Photo: Bürglin

Wu and Zhang (2006) studied habitat selection of Mishmi Takin in Cibagou Nature Reserve, Tibet, China. The Takins had different habitat preferences during the seasons. In winter they actively selected for Rhododendron-coniferous forest, Fargesia-coniferous forests and Theropencedrymion. In spring they choosed Fargesia-coniferous forests and Theropencedrymion. In summer Alpine meadow-shrubs and Rhododendron-coniferous forests were preferred habitats. It was suggested that food might play a key role on vertical migration of takin, whereas salt might also influence takin movements in summer. [17]

Food and feeding

Detailed studies of food habits have not been conducted. Takins are primarily browsers, feeding on shrubs and tree species, but forage preferences can vary seasonally. Forbs are an important forage in spring. Takins are able to bend or break smaller trees to feed on leaves. They also rear on their hindlimbs to reach higher vegetation. Salt licks are favoured sites. [16]

Takins are primarily browsers. They rear to reach higher vegetation. Female in June. Photo: Bürglin / Tierpark Berlin

Mortality / Predators

Larger predators probably do not cause significant mortality because they are rare. [16] In the Mishmi Hills Tigers, Dholes (Cuon alpinus – german: Rothund) and Asiatic Blacks Bears (Ursus thibetanus) are present.

Dhole attacking Takin female and young. In this picture where the female Takin lies (young huddled up against the mother) and the Dhlole sits, the Dhole’s line of attack seems to become clear: It just waits until the mother becomes inattentive … Photo: Dhritiman Mukherjee, Mishmi Hills, 2011-05-20

… and then lunges. It is not reported how this particular attack ended. Dholes also hunt in packs. Chances of subduing their prey is than of course much higher. Note sizes of the Dhole and the calf behind the mother. The Dhole has been described as combining the physical characteristics of the Gray Wolf and the Red Fox. Photo: Dhritiman Mukherjee, Mishmi Hills, 2011-05-20

Breeding

first mating: at 3,5 years of age; but males probably do not participate in mating until they are several years older. Older males probably do most of the mating. [16]

rutting season: probably August to September [16]

lambing season: March and April [16]

behaviour: females probably do not leave female herds to give birth.

young per birth: one [16];

Activity pattern

Takins in general are usually most active in early morning and late afternoon but in winter they may feed intermittently throughout the day. [16]

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

Detailed studies are lacking. Takins in general make seasonal movements from alpine meadows in summer to lower-elevation forested habitats in winter. Herds that exceed 100 animals form in spring, but large herds break up into small groups of 10 to 40 animals by autumn. Single males or two males together are common. [16]

Status

IUCN classifies the species as „vulnerable“. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [14]

China: No rigorous estimate has been made of the total Chinese population, but Wang (1998) estimated about 3.500, mostly in Tibet.

Myanmar: Populations are decreasing because of hunting for bushmeat (by trapping and crossbow), and is now rare (Than Zaw pers comm. 2006). [14]

India: no estimates available

Threats

In general illegal hunting, habitat loss due to deforestation, and habitat degradation due to livestock use of forage resources are major threats. [16]

A Mithun, the domesticated form of a Gaur, at Mishmi Hills. There owners let them freely roam in the forests. According to local guide Drama Mekola they tend to stay close to the road. Photo: Bürglin

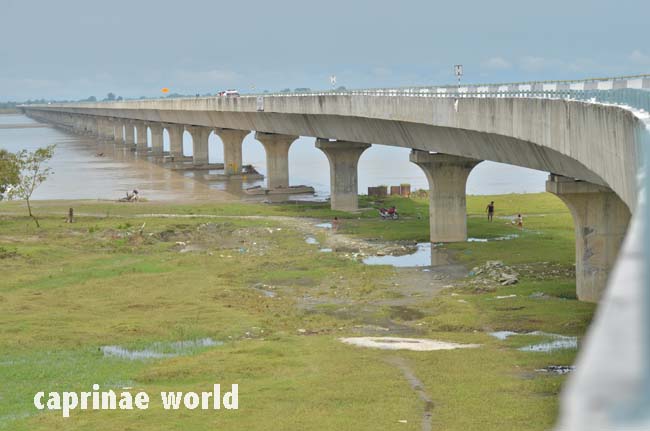

The Dhola-Sadia bridge – India’s biggest – opened 2017. It is an important piece of the puzzle making the Northeast of India more accessible. The planners in Delhi want to construct 160 dams in the area … Photo: Bürglin

In Tibet illegal hunting is the main threat, but habitat destruction caused by deforestation is also serious (Wang et al. 1997, Wang 1998). [14]

In Myanmar populations are threatened by trapping and crossbow hunting for bushmeat (Salter 1997). [14]

Conservation

In China, all subspecies are protected from direct exploitation by their inclusion under Category I of the National Wildlife Law of 1988, although a small number are taken yearly in trophy hunts. In the remote areas where this subspecies lives in China, local people may not be aware of its legal status. [14]

In China Mishmi Takin occur in the following reserves:

- Nujiang Nature Reserve, North Yunnan (established in 1981; herds of greater than 100 animals have been seen here (Lu, 1987).

- Gaoligongshan, Yunnan

- Cibagou Nature Reserve, Tibet (Wu and Zhang 2006)

- Dong Jiu Nature Reserve, Tibet (MacKinnon et al. 1996) [14]

In India the Mishmi Takin is classified in schedule I of the Wildlife Protection Act of India. [16] In India and Bhutan they are not legally hunted. In India, Arunachel Pradesh, the subspecies occurs in the following reserves:

- Namdapha National Park

- Mouling National Park

- Dibang Willdife Sanctuary,

- Kamlang Wildlife Sanctuary

- Dihang-Dibang Biosphere Reserve (Singh 2002). [14]

In Myanmar the legal status of Mishmi Takin is uncertain. They occur mainly within protected areas (Than Zaw, pers comm. 2006). [14]

Conservation measures proposed are:

1) Complete a population census of the Mishmi Takin;

2) develop a co-operative program between Chinese and Myanmar authorities to strictly forbid hunting of this animal;

3) locate potential protected areas. [14]

Recreational Hunting

not a factor

Ecotourism

Sightings of Mishmi Takins are very rare. Some have been made at Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, Nyingchi, Xizahg/China. Some sightings are reported from the Mayodia Pass, Mishmi Hills, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Here is my own Mishmi Hills trip report

Literature cited

[1] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[14] Song, Y.-L., Smith, A.T. & MacKinnon, J. 2008. Budorcas taxicolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3160A9643719. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3160A9643719.en. Downloaded on 20 February 2019.

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[17] Wu, P. and Zhang, E., 2006: Habitat selection of takin (Budorcas taxicolor) in Cibagou Nature Reserve of Tibet, China. Acta Theriologica Sinica 26(2):152-158