The Nilgiri Thar is the only member of the tribe Caprini that lives in the tropics (3), or south of the Himalayas in India respectively. (1)

Names

English: Nilgiri Tahr (1). The Nilgiris (meaning: Blue Mountains) form part of the Western Ghats, a mountain range in the Southwest of India. The word „tahr“ comes from the Nepali language and was first used in English writing in 1835. (5)

French: Tahr de Nilgiri (1), Mouflon des Nilgiri (3), Mouflon des Nilgiris (Wolfgang Dreier – pers. comm.)

German: Nilgiri Tahr (3), Nilgiritahr (1)

Malayalam: Varayadu (1)

Russian: Нилгирийский тар (1)

Spanish: Tahr del Nilgiri (3), Tahr de Nilgiri (1)

Tamil: varai ad, varai adoo (meaning: cliff goat) (1)

Taxonomy

Kemas hylocrius Ogilby, 1838

Type locality: Nilgiri Hills, South India (3)

Formerly classified in the genus Hemitragus (the genus of the Himalayan Tahr), Ropiquet and Hassanin (2005) placed the Nilgiri Tahr in the monotypic genus Nilgiritragus, based on analyses of four molecular markers. (1) Nilgiritragus is a sister-group of Ovis, the genus of the sheep. (3, 4) No subspecies are recognized. (2)

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

Kemas hylocrius Ogilby, 1838; (1)

Capra (Kemas) warryato, Gray 1842, 1852; „Warryato“ is an anglicized rendition of the Tamil term „varai adoo“ for the Nilgiri tahr. (1)

Hemitragus hylocrius, Blyth 1859 (1)

The interesting tangle of the Nilgiri Tahr’s names

Ogilby based his species name hylocrius on the understanding that its local name was „jungle sheep“ (jungle or wood corresponding to the root hyla and the Greek krios, which means ram). However, amongst the English speaking community in the High Range, „jungle sheep“ referred to the barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), wheras „ibex“ was the longstanding name for the Nilgiri Tahr. (1)

Rice (1984) meant that Gray’s warryato (an anglicized rendition of the Tamil term „varai adoo“ – meaning „cliff goat“) was a much more appropriate name (1), but Rice couldn’t change it, because of the rule of precedence. Therefore Ogilby’s hylocrius remained as the standard name.

Then in 2005 Ropiquet and Hassanin placed the Nilgiri Tahr in the monotypic genus Nilgiritragus, based on analyses of four molecular markers (1) and it was ascertained that the Nilgiri Tahr is related to Ovis – the genus of the sheep. (3) Therefore Ogilby at the beginning with his hylocrius = „jungle sheep“ couldn’t have choosen a more appropriate name for a beast that is sheeplike and lives close to the jungle, but is not quite enough a sheep to be included in Ovis, the genus of the „real“ sheep.

Similar species

It has to be made clear again: Even though the name „Tahr“ suggests a closer relationship between the three tahr species, the Nilgiri Tahr is a separate lineage. Nevertheless the tahr species feature similarities. These are the distinctions:

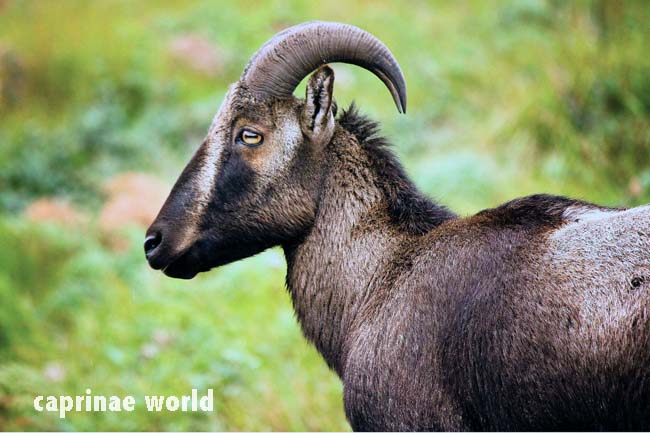

The Nilgiri Tahr is the largest of the Tahrs, being just slightly larger than the Himalayan Tahr. (5) Also the horns of the Nilgiri Tahr are larger than those of the Himalayan Tahr. (1) Unlike the coat of the Himalayan Tahr, the coat of the Nilgiri Tahr is short, probably as an adaption to the wet climate this species inhabits. The horns also lack the ridged keel seen in Himalayan Tahr. Females have two nipples, unlike the two other species of Tahr, which have four. (5)

Distribution

Southwest India in the Western Ghats range along the border with the two Indian states Kerala and Tamil Nadu. (3) The present distribution of the Nilgiri Tahr is limited to approximately 5 percent of the Western Ghats, although not along the border between these two states. At the beginning of the 20. century the range of tahr probably extended northward at least to the Brahmagiri Hills of southern Karnataka. (2) Today its range extends still over 400 km north to south. (1)

General description

length / head-body: males 150 cm, females 110 cm (1)

shoulder height: 80-100 cm (3); females: 80 cm; males: 100-110 cm (1)

weight: 50-100 kg (3); females: 50 kg; males: 100 kg (1)

A male Nilgiri Tahr. Note the overall dark colour and the lighter saddle patch. Photo: T. Anil Kumar

pelage color males:

- overall: dark brown to blue-slack (3), dark yellowish-brown to a deep chocolate brown (1)

- saddle: tan, off-white, white, silvery – depending on age (1); Rice (1989) described saddle back classes (1):

- about 6 years: saddle is off-white or tan; there is black coloration on the legs but shoulders and neck are dark brown

- at 7 years: the saddle may be silvery with the black coloration of the legs extending onto the shoulders, but not the withers

- over 8 year-old males: show a silvery saddle with the black coloration extending to withers and neck

Presumably well over-8-year-old male. Note: Not only are saddle patch, area around carpal joints and facial stripe almost white, also back of neck and shoulders are very light-colored. Black extends to the withers. Photo: Wolfgang Dreier

- face: the dark muzzle is separated from the dark cheek by a pale stripe, (3) which drops from the forehead towards the corners of the mouth (1), no beard (5)

- particulary dark body parts in males: shoulder, sides of abdomen, front of legs, sides of face and front of the muzzle (1), mane and dorsal stripe

- light / white body parts: throat, abdomen, carpal joints (3), facial stripe, saddle (1)

- mane: dark, short and stiff on the back of the neck and withers (1)

pelage color females:

- overall: In contrast to the striking pelage of the male lighter in colour (1), dusky-brown (3), yellowish brown to gray (5)

- carpal patch: black (1)

- facial markings: present, but only faintly (1)

- area around eys and cheek below it: brown (1) or orangey

in both sexes:

- underparts: paler (1)

- mid-dorsal band: dark, extending the length of the back (3), less conspicuous in females (1)

- mane: dark, less conspicuous in females (1)

- sides of the neck: sometimes lighter (1)

Pelage development

Nilgiri Tahr show particular stages in pelage development, which diverge between the sexes as they mature. At birth, both sexes have a generally gray coat with no facial markings or carpal patches. At 10 to 14 weeks they grow a fluffy tan coat, which is shed at about 20 weeks. After shedding the tan coat, they are again gray overall with black carpal patches, an indistinct light-colored facial stripe and dorsal stripe. Females never lose this pelage. Adult males, however, develop a completely distinct pelage as described above. (1)

horns (males): length 28-44,5 cm (3), ewes: 26 cm, males: about 44 cm; mean: 39,1 cm (1); basal girth 12,7-25 cm (3); mean: 21,4 cm (1)

sexual dimorphism: pronounced (1)

longevity: at least 9 years (2)

diploid chromosome number: 58 (3)

Horns

The horns in both sexes curve uniformly back. They are almost in contact at their bases. (1) The keel of the horn is confined to the inner edge. (3) The outside and inside curves are constant except for the last few centimeters. The tips diverge slightly due to the plane of the horn being divergent from the body axis posteriorly, and tilted slightly so as to converge dorsally or as Rice (1984, 1989) explained it: „There is no twist or flare to the horns, but their axis is about 20° off that of the skull, so the tips diverge moderately.“ (1)

The inside horn surface is nearly flat, and the back and outside are rounded. Promiment annular growth rings stand out amidst transverse wrinkles, which cover approximately two thirds of the horn surface; the tips are smooth. The horns of males are heavier and longer than those of females, due to the males‘ high initial horn-gowth rates through their second and third years (Riche 1989). Males reach maximum horn lenghts of about 44 cm and ewes‘ horns attain about 26 cm. Mean tip-to-tip spread in 19 specimens was 14,6 cm. On average horns of the Nilgiri Tahr are larger than those of the Himalayan Tahr. (1)

Presumably female. Note how the keels are confined to the inner edge of the horns. Photo: Sankara Subramanian

Habitat

The Nilgiri Thar is the only member of the tribe Caprini that lives in the tropics. Annual temperature fluctuations are not pronounced at elevations of 1200-2600 m in the Western Ghats, where they occur. (3) Populations as low as 900 m may or may not represent pre-human extent of occurrence in elevation. (2) They live near cliffs and steep slopes; rolling grasslands provide their preferred forage. Some areas receive an average annual rainfall of 4000 mm, mostly from June to August, during the monsoon. The grasslands are on steep slopes below cliffs and among rock slabs, interspersed with shrubs and forested deep valleys; trees in the thar’s habitat rarely exceed ten meters in height. (3)

The associated stunted, evergreen forests are locally known as „shola“. Rice (1984) noted that Nilgiri Tahr infrequently use these shola forests, mostly along their margins. However, observations of male groups in the Rajamalai area during their times of sexual segregation indicated that males often fed within large shola-forest patches. (1)

Cliffs, which provide security, are a limiting factor for the distribution of the thar. Nilgiri Tahrs are distributed in subpopulations, some with limited exchance of individuals. (3)

Mortality / Predators

Leopard (Panthera pardus), Dhole (Cuon alpinus) (3)

Food and feeding

Primarily grazers, with grasses comprising a much greater volume than forbs, shrubs, and trees. During the dry season, browse consumption increases. In drier, lowland habitats, they are probably primarily browsers. They occasionally feed at the edges of forest patches. (3)

Males and females have different habitat preferences. Areas used exclusively by males apparently contain greater amounts of the preferred grass than is available in habitats used by females. This may be related to a trade-off – of foraging opportunities for offspring security – in the selection of habitats closer to cliffs, where the lambs and ewes are more secure from predation. (1)

Breeding

mating: July-August – during the monsoon season. Unlike temperate caprins, whose mating season occurs during the end of the period of decreasing daylength, Nilgiri Tahrs mate during the period of increasing daylength. (3) As the rut approaches, males are thought to move extensively in search of estrous females but after the rut they move very little (Madhusudan 1995), probably in order to regain physical condition lost during vigorous rutting. (1)

gestation: 175-185 days (3); for about 180 days (2); 174-201 days (1)

births: Most births occur in January-February – during the period of least thermal stress. Usually Nilgiri Tahr have single offspring, twins are extremely rare. Some females whose offspring die at an early age conceive twice in one year and hence can have two young per year. Second births occur during the monsoon, during which period newborns are subject to thermal stress, that is, they are exposed to wet, cold, windy weather and have a higher mortality than those born during January and February. (3)

weaning: 4 to 6 months (5)

sexual maturity: at around three years of age (2)

Activity patterns

Most tahrs feed in the early morning until about 8 am. From 10.30 am to 2.30 pm about half are inactive. A second feeding peak occurs after 4 pm (3)

Movements, home range and social organisation

Basic social units consist of mixed groups and male groups. (3)

Mixed groups (females, offspring, subadults, and during the rut, adult males) average 42 (2-150) animals.

Male groups form during the non-mating season and have an average of three (2-20) animals, but solitary males are common.

Populations in two areas consisted of the following sex and age groups:

adult males: 13,4 % and 15,2 %

subadult males: 7,9 % and 4,2 %

females: 34,2 % and 33,6 %

yearlings: 18,9 % and 17,3 %

young: 25,6 % and 29,6 %

Density increases with the increase in cliff area. The population in the Eravikulam National Park had a mean density of 6,27 ind/km² in April, the highest tahr density recorded throughout their range. Females comprised about 40-45 % of the combined subpopulations.

The ration of young-of-the-year to adult females was 30-90:100.

The yearling ration was 20-55:100 females.

The sex ratio varied from 53,7 to 66,7 males:100 females, with a mean of 59,7 males:100 females.

Annual mortaliy within the park was 44-52 % for young, 31-37 % for yearlings and 17-25 % for adults. At birth, life expectancy was 3-3,5 years.

Herds continually change members between groups. Especially older males are rarely permanent members of mixed herds, but rather continually enter and leave mixed herds.

Social behaviours include butting horns, but most encounters involve body contact and displays. (3)

Population

Total numbers were estimated at between 2.000 and 2.500 individuals in the 1970s-1980s, and were thought to be stable (Davidar, 1978; Rice, 1988a, 1990). More recently Daniels et al. (2008) estimated the total population at no more than 1,800-2,000 individuals. An overall decline in the species was suggested by Daniels et al. (2008), although some populations appear to have remained stable in recent decades (Mishra and Johnsingh 1998). (2)

A workshop held in Coimbatore identified previously unknown, isolated populations (Easa et al. 2010). The population figure arrived at ranges between 2.617 (minimum confidence limit) and 4.232 (maximum conficence limit). However except for areas like Eravikulam and some others, there are no fully reliable estimates. The conclusions pertaining to these new areas need to be further confirmed by detailed fieldwork. (1)

The species current subpopulations

(as estimated by the Nilgiri Tahr Trust – retrieved 02 January 2007).

18 localities are known to support populations. Significant numbers occur in the hill areas around Anamundi (highest peak in India south of the Himalayas). The most southern population – at Ponmundi Hills – is almost at India’s southern tip. (1)

Nilgiri Tahr subpopulations

| Eravikulam National Park | 760-1000 |

| Nilgiri hills | 450, though now reduced to 75-100 |

| Grass Hills of Anamala | 250 |

| Swamaimala | 130 |

| Eastern Slopes of Ananmala | 125 |

| Top Slip and Parambikulam | 120 |

| Highwavy mountains | 100 |

| Vellakaltheri | 90 |

| Ashambu Hills | 70 |

| Mudaliar oothu | 70 |

| Elival Mala | 60 |

| Palani Hills | 60 |

| Thiruvannamalai peak | 40 |

| High Range | 30 |

| Nelliampathi Hills | 30 |

| Silent Valley | 30 |

| Siruveni Hills | 20 |

Major Threats

Principal threats are habitat loss (mainly from domestic livestock and spread of invasive plants) and poaching (Daniels et al. 2008). The general trends of decline even in the best managed Tahr habitats indicate that the total population of the species does not exceed 2000 at present and a conservative estimate would place the numbers within the 1.800-2.000 range (Daniels et al., 2006).

Currently, the only populations with more than 200 individuals are in Eravikulam National Park and in the Grass Hills in Anamala. The most recent information from the Nilgiri hills (Mukurti Wildlife Sanctuary), which previously had more than 300 tahr (Davidar, 1978; Rice, 1984; Schaller, 1971), indicates that only between 75 and 100 individuals remain. Wattle (Acacia mearnsii) plantations and cattle apparently no longer threaten the Mukurti population, so their decline is probably due solely to illegal hunting. The status of the other smaller populations (many of which are less than 100 individuals), which are also subject to continued illegal hunting, can be considered precarious. Similar population decreases and threats to the species were reported in a survey in Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (Rai and Johnsingh, 1992). (2)

Populations of these animals are small and isolated, making them vulnerable to local extinction. Habitat patches for Nilgiri Tahr are naturally discontinuous, but some habitat fragmentation may have anthropogenic causes (C. Rice pers. comm., 2008). The species faces competition from domestic livestock, whose overgrazing has allowed for the invasion of graze-resistant weedy species into preferred meadows, thus in competition with the native grasses that tahr prefer (Mishra and Johnsingh, 1998). Continued conversion of tahr habitat to agricultural land has resulted in a present distribution that is about one-tenth of its historical range (Mishra and Johnsingh, 1998; Kannery, 2002; IUCN, 2004). (2)

Conservation Status

The Nilgiri tahr is fully protected (Schedule I) by the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972, although this protection is rarely enforced and illegal hunting is a major threat (Kannery, 2002; IUCN, 2004). (2)

The following areas offer an important degree of protection to the Nilgiri Tahr:

- Eravikulam National Park (NP),

- Silent Valley NP,

- Mukurti, Anamalai, and Parambikulam Wildlife Sanctuaries,

- Srivilliputhur Grizzled Giant Squirrel Sanctuary,

- Kalakadu-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve (2)

- Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve – including Bandipur, Nagarhole and Silent Valley National Parks, the Mudumalai, Mukurti and Wynad Wildlife Sanctuaries, the Bolampatti Reserved Forest and the proposed Karipuzha National Park (M. Alembath, pers. com.)

The following institutions are active in promoting Nilgiri Tahr conservation:

- Nilgiri Wildlife Association,

- High Range Wildlife Association,

- Ramnad District Wildlife Association,

- Kerala Forest Research Institute,

- Bombay Natural History Society,

- Wildlife Institute of India, (2)

- Mohan Alembath / www.nilgiritahrinfo.info

Proposed conservation measures :

The Nilgiri tahr requires continuous study and monitoring, because its small and isolated populations are extremely vulnerable.

With proper conservation, including habitat maintenance and minimising mortality due to hunting, it is possible that with time, the species could be considered no longer threatened, if the following are accomplished:

1) Enact management proposals that include the systematic monitoring of tahr populations, as well as possible re-introductions (Rice, 1988a, 1990; Rai and Johnsingh, 1992). There is good potential for re-introductions in areas such as the Kalakadu-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve where several highlands had small populations of tahr some 20 to 40 years ago, but today are very small or non-existent (Rai and Johnsingh, 1992).

2) Consider low impact recreational use (e.g. trekking, fishing) of suitable areas, especially where such activities would benefit (and compensate) the local economy for restrictions on traditional activities such as hunting by local inhabitants.

3) Co-ordinate Nilgiri tahr with other wildlife and habitat conservation efforts, because the Western Ghats are one of India’s major wildlife areas. (2)

Trophy Hunting

not a factor

Ecotourism

According to eraviculam.org Eravikulam National Park is „the most sought after destination in Munnar“. The slogan of this park is „Home of Nilgiri Tahr“. It is therefore well conceivable that the species has a bearing as a visitor magnet.

Literature cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Alempath, M. & Rice, C. 2008. Nilgiritragus hylocrius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T9917A13026736. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T9917A13026736.en. Downloaded on 19 September 2017.

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princton University Press.

(6) Simpson, J. A., and E. S. C. Weiner. The Oxford English Dictionary. 20 vols. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.