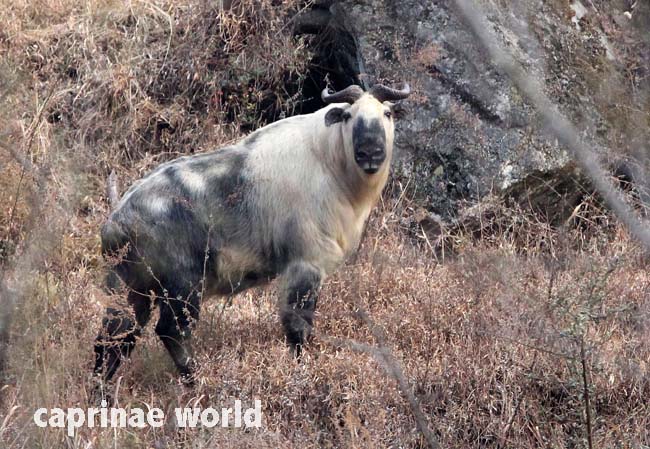

The Sichuan Takin is the neighbour of the Golden Takin to the west. Blotches of grey appear on its otherwise golden yellow pelage.

Names

Chinese: líng niú sì chuān yà; líng niú qín lĭng yà [2] – ((editor’s note: the second name obviously refers to the Qinling Mountains, which is home of the Golden Takin))

English: Sichuan Takin [2]

French: Takin de Sichuan [16]

German: Sichuan-Takin [16], Szechuan Takin [2] – ((Editor’s note: outdated))

Russian: Сычуаньский такин [2]

Spanish: Takin de Sichuan [2, 16], Takin del Tibet [2]

The subspecific name tibetana is based on mistaken geographic information (Lydekker 1908). [2]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

Budorcas taxicola [sic] tibetana, Milne-Edwards, 1874, Moupin, Sichuan, China [16]

Budorcas t. tibetana, Milne-Edwards, 1874; W Sichuan, S Gansu [13]

Budorcas taxicolor sinesis, Lydekker 1907 [2]

Budorcas taxicolor mitchelli, Lydekker 1908 [2]

Budorcas taxicolor tibetanus, Lydekker 1908 [2]

Taxonomy

Some authors see the Sichuan Takin as a full species (Budorcas tibetana) [1, 4, 16], others prefer to separate it as a subspecies (Budorcas taxicolor tibetana) [2, 6, 13].

diploid chromosome number: 52 [2]

Similar species / subspecies

The Sichuan Takin is in terms of pelage colour similar to the Golden Takin, but the trunk of males is often a mix of orange and grey or tawny and grey, instead of the pure tawny or orange coloured pelage of the Golden Takin. Compared to Mishmi and Bhutan Takin the coat of the Sichuan Takin is overall lighter.

Distribution

by country / state: China / West Sichuan, South Gansu [6, 16], Yunnan, Xizang [2]

The Sichuan Takin is found (largely [2]) along the eastern margin of the Tibetan plateau. Here, its distribution runs from the Min Mountains along the Sichuan-Gansu provincial border, south through the Qionglai Mountains west of Chengdu to the border with Yunnan Province. Records of this Takin have been found from more than 50 counties in Minshan in the north, Xianling in the west, as well as in the Qionglai Shan in the centre, and the Liang Shan in the south. [6] The distribution range appears to extend west into northeastern Xizang AR (Tibet) in deep river valleys (i.e. Ngawa, Drukchu). It also covers a small portion of northern Yunnan province adjacent to Liangshan Autonomous Prefecture in Sichuan Province. [2]

Description

general appearance

Takins have large, bovine-like bodies, a shaggy coat including long hair on the side and under the jaws, stout legs, prominent dew claws, and are taller at the shoulder than the hip. [16]

Descriptions of the body sizes are not consistent: Damm and Franco (2014) state that the Sichuan Takin is larger than Golden and Bhutan Takin. Matschei (2012) writes that Sichuan and Golden Takin are bigger than the Mishmi Takin. Castelló (2016) notes that the Sichuan Takin is the largest Takin. Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) do not see any differences in body sizes. The following measurements of Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) probably refer to Takins in general [16]:

body length: 170-220 cm – males are significantly larger than females [16]

shoulder height: 107-140 cm [16]

weight: 150-350 kg [16]

tail: 10-22 cm [16], often hidden beneath shaggy fur

The main varying scull character in Takin species / subspecies in the view of Groves and Grubb (2011) concerns the nasals, which are, on average, most arched in the Sichuan Takin („Pal nas ht“ i.e., the height of the most convex part of the nasals above the palate) [4]. In simple words that means that the Sichuan Takin has the most distinct roman nose. But the number of specimens examined (n=5) does not meet the basic requirements of statistics. Nevertheless the profile of the female on the photo below is very impressive. More research is needed.

Sichuan Takin female with impressive roman nose (see paragraph above). Photo: Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu, Tangjiahe, 2016-04-04

Colouration / pelage

Accounts on pelage colour are not consistent. At this place we mostly highlight the descriptions of Damm and Franco (2014), which are most comprehensible.

pelage in general: light yellow grey or straw coloured; blotches of dark grey appear on its back, legs and rump; some specimens show fore quarters with orangey, reddish-brown to yellow colour, with the hindquarters predominantly darker and greyer. [2]

summer coat: richer golden yellow [2]

Sichuan Takin male during the breeding season. Note the intensly coloured head and neck. A black muzzle is missing in this specimen. Photo: Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu, Tangjiahe, 2015-07-15

winter coat: more greyish; progressing to iron grey or blackish on limbs and hindquarters through the winter [2]

Sichuan Takin young. All young of the different Takin subspecies are rather hard to differentiate. They all appear more or less uniformly brown with somewhat darker limbs and a lighter back. Photo: Bürglin, Tierpark Berlin, 2016-06-06

„Golden“ Sichuan Takin?

From the number of Sichuan Takin photos available, it seems that specimens with blotches are typical. But there are also specimens occurring without darker patches on their pelages. Damm and Franco (2014, Vol. II, page 11) show a photo of such a Sichuan Takin, that they do not further comment. It shows a purely yellowish bull that looks rather than a Golden Takin. On the two photos below there are two more specimens without blotches.

The Sichuan Takin’s range borders that of the Golden Takin (There is a gap between the two ranges, but it is likely that – at least in former times – there was some exchange between the populations. It is therefore easily comprehensible that individuals within the range of the Sichuan Takin show physical characteristics of the neighbouring subspecies – and vice versa. More research is needed.

Sichuan Takin male with uniform body colour. Photo: Coke Smith/Tangijahe Nature Reserve, Sichuan, China

Sichuan Takin female during the breeding season. Note the absence of dark blotches on the trunk. Photo: Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu, Tangjiahe, 2015-08-29

lower limbs: in some almost black [2]

darkish parts on head: ears, a ring around the eyes, and the front of the lower part of the face, as well as the tip of the chin, appear darkish, sometimes almost black [2]

Black nose – indicator of age: becoming extremely conspicuous in older specimens; moreover in winter dark areas become more blackish, than in summer [4]. Sichuan Takin male. Photo: Bürglin, Tierpark Berlin, 2008-10-25

Male with allegedly typical pelage pattern. Where is the saddle? (see paragraph above). Photo: Coke Smith, Tangjiahe, 2013-03-09

beard / mane: a shortish fringe of longer hair behind the chin extends a little way down the neck like a beard or bib; with lighter hair, more in some individuals than in others [2]; present in adults [4]

mid dorsal stripe: from tail to withers [2]

young calves: more brownish all over, whereas subadults approach the colour of the adults [2]

Horns

As in all Takins horns grow slightly upward, and then turn outward and backward with the horn tips upward. Males have larger horns than females. [16] The horns of Sichuan Takin may be somewhat more slender than those of Mishmi Takin (Lydekker 1908), and appear, in some cases at least, more arched and more distinctly ridged at base than in the typical species ((editor’s note: the Mishmi Takin?)). [2]

Rowland Ward (RW) has only three entries for Sichuan Takin, the longest horns from Tai-pei Shan (1921) attaining 54 cm in length and 20,5 cm in basal circumference, the other two trophies from 1921 and 1902 respectively are only slightly smaller. Two tip-to-tip spreads are recorded (34 cm and 29,8 cm). Safari Club International (SCI) lists 15 heads (taken between 1994 and 2005): the median length of both horns measured across the boss stands at 82,2 cm and the median boss with (measured across the base of the horns) at 29,5 cm. The individual measurements of RW and SCI are not comparable. [2]

Hornless Takin – presumably due to an accident or an illness. Photo: Coke Smith, Tangjiahe Nature Reserve, Sichuan, China

Habitat

Sichuan Takins usually inhabit elevations at 1.500 to 3.000 metres. [16] They can be found at the uppermost limits of the tree line, reaching elevations ranging from 1.200 to 4.000 metres while in winter they find shelter and forage in the valleys. [2]

Like all Takins the Sichuan Takin moves with ease in steep terrain – sometimes causing little landslides. Photo: Coke Smith/Tangijahe Nature Reserve, Sichuan, China

In the Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve in Sichuan, there are four principal vegetation zones, ranging from timberline above 3.200 to 3.300 metres to mixed coniferous and broadleafed deciduous forest at 1.700 to 2.100 metres; rhododendron and bamboos form an understory component at lower elevations. Vegetation communities below 2.200 metres have been modified by human activity. [16]

Takins readily utilize secondary growth in the reserves where lumbering is no longer allowed and, in such areas, numbers may be increasing (Schaller et al. 1986). [2]

Food and feeding

Sichuan Takins are known to feed on 130 plant species, including 70 shrub and tree species. They are primarily browsers, but forbs are an important forage component in spring. They also frequent salt licks. Their tall bodies allow them to reach browse unavailable to smaller ungulates and their broad, flexible lips enable efficient and selective foraging. Takins may push over or break smaller trees to obtain browse. The also rear up on their hindlegs to reach browse up to 2,5 metres above the ground. [16]

Mortality / Predators

Leopards (Panthera pardus) and Dholes (Cuon alpinus) feed on takins, but these predators are scarce. [16]

Breeding

sexual maturity: ca. at 3,5 years [16]

rutting season: late July to August [7]; probably August to September [16]

gestation: 210 days [16]

lambing season: March and April [16]

young per birth: only one [16]

Rare event: Sichuan Takin female with two young. Photo: Smithsonian Institution, www.si.edu, Tangjiahe, 2016-04-21

Activity pattern

Takins in general are usually most active in early morning and late afternoon but in winter they may feed intermittently throughout the day. [16]

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

Takins in general make seasonal movements from alpine meadows in summer to lower-elevation forested habitats in winter. One Sichuan Takin male was observed to cover about 6 kilometres when foraging along a valley in autumn and winter. Based on 51 herds observed in the Tangjiahe National Nature Reserve, mean herd size was 39,6 animals with most herds composed of 10 to 45 animals. Estimated density of Takins was 1,2 to 1,3 ind/km². [16]

In another study of group composition and herd size in the same area, 85,7 per cent of the males were solitary, 8,3 per cent were groups of two males, and 4,2 per cent consisted of three males. Most mixed herds, made up of females, young, subadults, and adult males, consisted of 10 to 35 individuals; one herd of 93 to 112 Takins was recorded. Larger herds form in May after parturition and split into smaller groups by autumn. Young and yearlings each comprised 20 per cent of the population in May and November, indicating low mortality in these age groups. The sex ratio was 50 males:100 females. [16]

Status

IUCN classifies the species as „vulnerable“. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [6]

No total population for the Sichuan Takin (Budorcas taxicolor tibetana) estimate in China has been made, but several thousand animals are believed to inhabit the Qionglai and Min Mountains [6], where Schaller (1985) estimated highest densities. Damm and Franco (2014) assume that Sichuan Takins are the most numerous of the Takin subspecies. [2]

A survey of Sichuan Takin populations carried out in 1975 in the Wolong and Tangjiahe Nature Reserves (Qingchuan county), estimated 191 (Wu et al., 1987) and 370 to 410 (Ge et al., 1989) animals, respectively. Large herds numbering as many as 45 to 100 individuals have been seen occasionally in Tianguan, Baoxing, Pingwu and Qingchuan. Other population observations estimate the young to account for 17,8 per cent, the sub-adults for 13,3 per cent and the adults 68,9 per cent, while the adult male to female sex ratio is 2:1 (Wu et al., 1990; see also Schaller et al., 1986). [6, 12]

Threats

Overhunting (Poaching) has resulted in local extirpation of this takin in some areas of its range, and recovery has been slow despite legal protection measures. Habitat loss and disturbance from tourism are also significant threats. [6]

Conservation

The Sichuan Takin is considered a national treasure in China and has been named a „First Order Priority Species“, giving it the highest level of legal protection. [2] Between 1963 and 1978, a total of 10 nature reserves were established in Sichuan to protect endangered animals. Most of them also provided protection for the Sichuan Takin. [6]

Protected areas with this subspecies include [6]:

Baishuijiang (Gansu), Baihe, Fengtongzhai, Jiuzhaigou, Labahe, Mabian Dafending, Tangjiahe, Wanglong, Wolong, Xiaozhaizigou (Sichuan)

Since that time, the nature reserve system with habitat for the Takin has continued to expand, including:

Huanglongsi and Meigudanfengding (Sichuan), Jianshan and Tou’ersantan (Gansu) [6]

In the course of the Smithsonian Institution’s Giant Panda projects, the camera traps have also delivered photos of Sichuan Takin, which can be viewed at the Smithsonian Wild website. These projects are helping to establish a comprehensive mammal monitoring system in the area. [2] In respect of Takins one has to consider that a study, that aims to shine a light on forest dwelling Giant Pandas, is only restrictedly suitable for Takins, which move temporarily outside the Panda’s habitat, e.g. above tree line during the summer.

The primary conservation measure proposed is further scientific study on the ecology and management of this subspecies is necessary for its long term conservation. [6]

Captive breeding has been carried out in Chengdu Zoo since 1978 (Hu et al. 1984). [6]

Recreational Hunting

not a factor

Ecotourism

Mammal watchers have reported sightings from Tangjiahe and Wolong National Nature Reserves, whereas most sightings are probably made at Tangjiahe.

In Tangjiahe Nature Reserve Sichuan Takin can be seen along the road in autumn. Photo: Christopher R. Scharf, 2014-11-08

Literature cited

[1] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[6] Song, Y.-L., Smith, A.T. & MacKinnon, J. 2008. Budorcas taxicolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3160A9643719. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3160A9643719.en. Downloaded on 25 February 2019.

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[12] Shackleton, D. M (ed.) and the IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 1997: Wild Sheep and Goats and their Relatives. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 390 + vii pp

[13] Smith, Andrew T. and Xie, Yan, 2008: A guide to the mammals of China. Princeton University Press

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.