The Chartreuse Chamois is seen as a subspecies of the Alpine Chamois. It has a very small and isolated distribution range in the Chartreuse massif at the western edge of the French Alps.

Names

English common names: Chartreuse Chamois [1], Carthusian Chamois – not common, but justified according to Carthusian Pink (Dianthus carthusianorum)

Dutch: Chartreusegems [Wikipedia]

French: Chamois Chartreuse [1, 5]

German: Chartreuse Gams [1], Chartreuse-Gämse [5], Kartäusergämse – not common, but justified according to Kartäusernelke (Dianthus carthusianorum) or Kartäuserkatze

Italian: Camoscio della Chartreuse [Wikipedia]

Spanish: Rebeco de la Cartuja [1, 5]

The name Chartreuse most likely derives from or grew in popularity with the Carthusian Order (french: L’Ordre des Chartreux). The order and Grande Chartreuse – the head monastery of the Carthusian order – were founded in 1084 by Bruno of Cologne. The monastery is located in the hard of the Chartreuse Mountains, near the commune of Saint-Pierre-de-Chartreuse.

Monastery „Grande Chartreuse“: The name „Chartreuse“ most likely derives from the Carthusian Order. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Taxonomy / similar subpecies

Rupicapra rupicapra cartusiana

Couturier, 1938 [1]

Looking at physical characteristics:

For Couturier it was all very obvious. In 1938 he wrote in „Le Chamois“, page 349:

„Depuis plusieurs années, chaque automne, en allant au Muséum de Grenoble, parmi les nombreuses têtes de Chamois apportées au préparateur, je reconnaissais toujours à l’aspect, à la physionomie, ·au milieu de tous les autres, les sujets provenant de Chartreuse. Je me mis à étudier cette forme spéciale; les résultats m’obligèrent à en faire une nouvelle sous-espèce.“

Every fall he went to the Natural History Museum in Grenoble. Among the many Chamois heads in the collection he „always“ recognized the ones from the Chartreuse massif. So he just „was compelled to make a new subspecies“. – This is what he found:

- dimensions above average („Le chamois de Chartreuse est d’un format au-dessus de la moyenne.“)

- heavy weight; heavier than the Alpine form („Un tel animal est inévitablement lourd. Les mâles adultes ont un poids variant de 40 à 50 kilos. Mais ces chiffres peuvent être depasses. Les femelles sont plus lourdes aussi de quelques kilos que celles de la forme type des Alpes.“)

- very dark winter pelage without brown or red hair as seen in Alpine Chamois („La livrée d’hiver est bien mieux caractérisée: elle est entièrement noire“ … On n’observe pas ici ces poils marrons ou roux qu’on voit disséminés dans la toison du Chamois des Alpes.“)

- horn curl insignificant („Le crochet est très peu marqué; en un mot, la corne se recourbe en arrière d’une facon insignifiante“)

- the transversal horn diameter at base is compressed („Bien souvent, le diamètre antéro-postérieur à l’origine du crochet est de 0,020, alors que le diamètre transverse est de 0,010. Je fais de ce signe un caractère de premier ordre. J’ai exceptionnellement remarqué une ébauche d’aplatissement chez des spécimens provenant d’autres massifs des Alpes; d’ailleurs, cette compression transversale n’est jamais aussi nette que dans la forme cartusienne.“)

- general scull measures are bigger than those from the Alpine form („Les dimensions générales du crâne, principalement les 3 longueurs, sont fortes et au-dessus des moyennes observées chez le Chamois des Alpes.“)

- nasal bones are broader („Les os nasaux sont

plus larges (0,018 à 0,019)“) - row of molars longer („Ce qui frappe à l’examen, c’est la grande longueur des rangées des molaires supérieures et inférieures.“)

- exceptionell size of molars and premolars – only surpassed be the Carpathian Chamois („D’une facon générale, la dentition est puissante et chacune des prémolaires ou des molaires a des dimensions (surtout la largeur) supérieures a celles de la forme alpine. … De plus, la longueur de la M3 inférieure se trouve comprise entre 0,017 et 0,020. … Pour cette dent, j’ai vu ces chiffres atteints ou depassés seulement par le Chamois des Carpates.“)

With all these findings no wonder Couturier concluded that the isolation of the Chartreuse Chamois is „exceptional“ („Dans l’aire générale de distribution géographique, il est exceptionnel de rencontrer un isolement, une insularisation aussi parfaits que dans le massif de la Chartreuse.“)

Unfortunately for Couturier other authors consider these quantitative and qualitative characteristics alone as insufficient to justify subspecific status. [1] Groves and Grubb (2011) do not confirm Couturier’s findings at all: „The Chartreuse Chamois overlaps in all described character states with chamois from the Alps, even if they are somewhat different on average.“

Damm and Franco (2014) indicate to quote Couturier with an average body mass of around 30 kg for males, 22 kg for females. This would be substantially lighter than the Alpine form. But Couturier (1938) actually indicates 40 to 50 kg and more for adult males.

The same authors mention „a few intermediate characteristics which place it (Chartreuse Chamois) as a link between the pyrenaica and rupicapra species.“ Unfortunately they don’t specify what characteristics are meant. They do mention a „cream colored neck patch“, but it becomes not clear if this is one of these characteristics (see below: colouration / pelage / neck).

Looking at genetics:

Pemperton et al. (1989) investigated the genetic variation in 53 individuals representing 6 Alpine Chamois (R. rupicapra) populations by starch gel electrophoresis, in order to determine the extent to which the Chartreuse Chamois (R. r. cartusiana) differs from R. r. rupicapra.

Across all populations studied 10 to 55 loci screened were polymorphic and average heterozygosity was typical for a mammal but high for a large mammal. As measured by Nei genetic distances, the cartusiana population was the most distinct, but no loci displaying fixed differences between populations were detected. [5] The genetic distances between the two phenotypes were found to be similar to the genetic distances between various Red Deer subspecies. [1]

Unfortunately, when Pemperton et al. carried out their study, individuals from the Alpine population had already been introduced into the Massif de Chartreuse. [4]

In summary, one can say that the justification for a separation into a subspecies on the basis of physical characteristics still remains doubtful. Nevertheless in view of the clear geographic separation and the genetic differences, the classification into a distinct subspecies seems justified.

Distribution

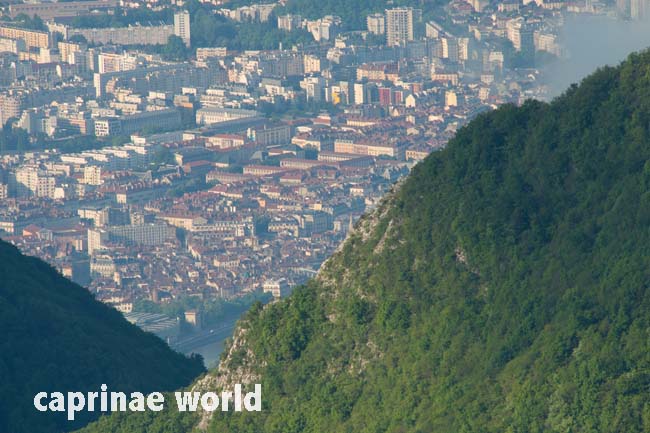

The Chartreuse Chamois is endemic to the Chartreuse Mountains in France, an isolated limestone massif at the western edge of the Alps between the cities of Chambéry and Grenoble. Eastwards and around the southern tip, the Chartreuse mountain system is isolated by the broad valley of the river Isère. In the north around Chambéry there is also a depression that connects the Isère with the Rhône valley. To the west the mountains level off to reach heights around 400 metres asl.

About 70 percent of the massif is covered by mixed conifer and decidious forests. [1] A smaller fraction of the area lies within the alpine zone. The highest mountain is Chamechaude (2082 m asl).

General description.

length / head-body: 115-125 cm [5]

shoulder height: 75-90 cm [1, 5]

weight males: 30 kg [1, 5], 40 to 50 kg [7]; females: 22 kg [1, 5]

horn length: 23-27 cm [5]; mean 21,8 cm; maximum 27,4 cm [1]

tail length: 3-4 cm [5]

karyotype: 2n = 58 [1]

Colouration / pelage

(in general like other Alpine Chamois)

overall body colour in winter: almost black [1]; black facial stripe, sides of neck, dorsal stripe, tail, shoulder, lower flanks and limbs are darker than rest of body

overall body colour in summer: pale brown [1]

underparts: pale [5]

legs: usually darker [5] than body

head: black and white facial mask.

Like in other Alpine Chamois, specimens with reddish pelage do also occur in Chartreuse Chamois. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

neck: In winter sides of neck are darker than other parts of body. A cream coloured neck patch [1] could indicate the relationship to the Pyrenean Chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica).

But Damm and Franco (2014) do not indicate the exact position and form of such a neck patch. During two field trips in December 2018 I found several animals with a v-shaped patch running down from the base of the ear on both sides of the spine (but such a patch does occur in other Alpine Chamois as well). And I found one female with a prolonged throat patch (note that sizes of throat patches in Alpine Chamois do vary). Further studies are needed! Do the v-shaped patches occur more often in Chartreuse Chamois? And are the prolonged throat patches typical for this subspecies?

In these two Chartreuse Chamois females a small hinted cream coloured neck patch is visible just behind the ear. Photo: Sophie Perroy

In this female (right) the right part of the neck patch has been marked. Photo Ralf Bürglin, 2018/12/14

In this male a v-shaped neck patch is visible as a continuation of the light-coloured area between the ears. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, 2018/12/14

In this female Chartreuse Chamois (left) the throat patch is prolonged. Right side: Southern Chamois female. Does the prolonged throat patch indicate the relationship to the Southern Chamois? Photos: Ralf Bürglin

In this male specimen from May a slightly lighter right neck side is only vaguely recognizable. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Horns

According to Couturier’s (1938) samples, the mean length of Chartreuse Chamois horns is around 21,8 cm, with maximums of 27,4 cm; mean height of 15,2 cm with maximum 19,5 cm and a mean span of 9,3 cm, maximum of 23,1 cm. [1] These measurements are lower compared to those of other Alpine Chamois (R. r. rupicapra).

As in other Chamois, males of Chartreuse Chamois have stronger hooked horns than females. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

The Office National de la Chasse et de Faune Sauvage (ONCF) states that Chartreuse Chamois show horns with large circumferences. [1] The horn measurements of Groves and Grubb (2011) of Chartreuse and other Alpine Chamois do not support these findings.

Chartreuse Chamois are said to have stronger horn bases. From the measurements available this is not comprehensible. Photo: Bürglin

Table 1: Horn measurements of Chartreuse and Alpine Chamois [4]

| R. r. cartusiana (males) | horn l | horn br tips | horn base ap | horn base diam |

| mean | 236,5 | 90,13 | 27,87 | 26,00 |

| N | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Std dev | 16,000 | 39,219 | 2,100 | 1,195 |

| min | 220 | 56 | 25 | 24 |

| max | 260 | 155 | 31 | 28 |

| R. r. rupicapra (males) | horn l | horn br tips | horn base ap | horn base diam |

| mean | 237,29 | 96,14 | 29,36 | 26,64 |

| N | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Std dev | 10,186 | 16,129 | 1,906 | 1,737 |

| min | 218 | 75 | 26 | 24 |

| max | 259 | 135 | 33 | 30 |

Habitat

Damm and Franco (2014) state that Chartreuse Chamois occupy mostly forests and usually spend the summers at low altitude in thickets of large coniferous forests and wooded canyons [1]. If this description of habitat selection and timing is accurate, than Chartreuse Chamois would be very different from other Alpine Chamois, which usually stay at alpine meadows during the warm season and descent to lower altitudes in winter.

Chartreuse Chamois habitat in spring at Chamechaude at around 1700 m asl. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, taken from Le Charmant Som

The pass Col de Porte in the left lower corner; Chamois habitat at Charmant Som (1867 m asl), upper right corner. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

During a field trip for the drawing up of this chapter on May 20th and May 21st 2018 five different groups of chamois with of a total of 11 animals were observed at Le Chamechaude (2082 m asl) and Le Charmant Som (1867 m asl). All of them were encountered in subalpine coniferous forests or above forest line respectively.

Predators

Lynx (Lynx lynx) is a common predator of chamois. It is present in the area. [6] Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are known to prey on chamois too. The species was confirmed during a trip to the area in May 2018.

Zwo Golden Eagles in the Chartreuse Mountains: potential predators of chamois kids. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Conservation Status / threats

The IUCN Red List classifies the Chartreuse Chamois as „vulnerable“. [2]

Factors threatening this subspecies,

food and space competition with domestic livestock, Red Deer and introduced Mouflon; hybridization with introduced Alpine chamois; over-harvesting and poaching; forestry; summer tourism and winter cross-country skiers. [2]

The subspecies was formerly restricted to a 60 km² area of state forest. Its population numbers and its spatial distribution were even more reduced between 1960 and 1970. The total population was estimated at 300 to 400 individuals in the 1970s and reached a low of 157 individuals in 1985, within a zone of around 6.000 ha (Roucher 1999). [1]

Restoration measures for the Chartreuse Chamois were started after 22 local hunting societies consented to a comprehensive management plan for the entire population. All hunting was stopped until 1990, when an acceptable number of chamois and an adequate population structure, allowing a sustainable harvest, had been reached. Harvesting started in fall 1990 at a 2 percent harvest rate, increasing to 4 percent in 1997 (Roucher 1999). Under intensive conservation management, the population has since increased to about 2.000 individuals (Lovari 2006). [1]

Chartreuse Chamois are threatened by various factors, but have recovered since the 1970ies. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Successful translocation within the original range to the eastern side of the Chartreuse area was conducted between 1990 and 1992. The population is probably still susceptible to random demographic or environmental events (Shackleton 1997; Lovari 2006). [1]

Hybridization with Alpine Chamois: Chartreuse Chamois had been extirpated in the northern end of the mountain massif. Instead of moving a few native Chartreuse Chamois from the core of the massif, the administrative authorities chose to introduce Alpine Chamois from other areas in 1974. These Alpine Chamois multiplied quickly despite high hunting quotas. Therefore there is a possibility that Alpine Chamois may hybridize with Chartreuse Chamois and threaten the genetic purity of the Chartreuse Chamois (Roucher 1999). [1]

Translocation to the Vosges Mountains: In 1956 Chartreuse Chamois were used for introductions into the Vosges Mountains, further north, close to the German border. There they hybridized with introduced Alpine Chamois. [1]

Trophy hunting

A number of Chartreuse Chamois is legally harvested every year, mainly by members of the local hunting societies. Detailed studies and data on harvested Chartreuse Chamois are not available. Figures for an annual harvest published in 2006 list 32 individuals being taken. [1]

Ecotourism

Trip reports of mammal watchers that mention Chartreuse Chamois are hardly available. But visitors of the area do mention encounters with chamois in blogs. It appears that for them the species enhances the attractiveness of the area.

The two mountains Le Chamechaude and Charmant Som in the south of the Chartreuse massif are very popular with hikers (Grenoble – 161.000 inhabitants – is situated only 20 km to the south).

Literature Cited

[1] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

[2] Aulagnier, S., Giannatos, G. & Herrero, J. 2008. Rupicapra rupicapra. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T39255A10179647. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T39255A10179647.en. Downloaded on 06 June 2018.

[3] Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.[5] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princton University Press.

[5] Pemberton et al., 1989: Genetic variation in the Alpine chamois, with special reference to the subspecies Rupicapra rupicapra cartusiana Couturier, 1938. Z. Säugetierkunde 54 (1989), 243-250, Verlag Paul Parey, Hamburg und Berlin

[6] KORA, 2016: The recovery of wolf and lynx in the Alps. Retrieved: 2019-11-19. http://www.kora.ch/fileadmin/file_sharing/5_Bibliothek/52_KORA_Publikationen/520_KORA_Berichte/KORA_Report_70_E_2016_The_recovery_of_wolf_and_lynx_in_the_Alps.pdf

[7] Couturier, M. A. J., 1938: Le chamois. Arthaud, Grenoble