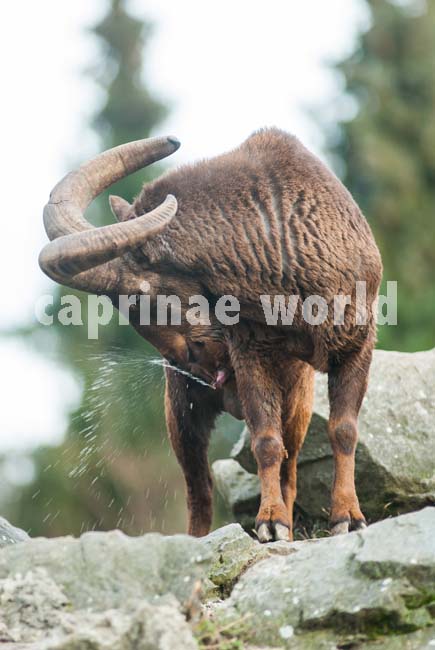

The Daghestan Tur has the thickest horns of all Capra species with the Kuban Tur a close second. It is endemic to the eastern part of the Greater Caucasus.

The males of this species are massiv, heavily built and have a somewhat elongated body on short stout legs. The head is well-proportioned with a slightly roman nose. (1)

English common names: East Causasian Tur, Eastern Tur (3), Daghestan Tur (1)

German: Dagestan-Tur (3), Ostkaukasischer Tur (1)

French: Bouquetin de Daghestan (3), Tur du Caucase oriental (1)

Spanish: Tur del Cáucaso oriental (3), Tur oriental (1)

Russian: дагестанский тур (1), Восточнокавказский_тур (Wikipedia)

Azeri: dagh kechisi

Balkar: zhugutur

Cherkess: k’urshazhe

Georgian: jikhvi

Ossete: dzebidyr

Taxonomy

Ovis cylindricornis (Blyth, 1841)

Type locality: Caucasus

There has been uncertainty in the past whether Daghestan Tur and Kuban Tur (C. severtzovy) are conspecific. They are marginally sympatric where their ranges meet and hybridize in captivity. Morphological and genetic data indicate probable hybridization in the wild. It is clear that the two are quite distinct morphologically and easily recognizable in the field. Monotypic. (3)

Distribution / countries occurence

East Caucasus stretching over a distance of 500 km in Georgia, Azerbaijan, and within the Russian Federation. (1,5)

Male Caucasian turs rutting with Dykh-tau Mountain in the backdrop / Caucasus. Photo: Igor Shpilenok / www.shpilenok.com

General discription

total length: head-body 178-192 cm (males), 135-141 cm (3). Males grow throughout life, while female cease growing by three years of age. (1)

shoulder height: 79-105 cm (males); 65-70 (females) (3)

tail length: 11-15 cm (3)

beard: 12 cm males – or shorter (shortest beard of all wild Capra species). When bend forward the beard does not reach beyond the chin. It is almost absent in summer. Females are rarely bearded. (3) Beard color is dark. (7)

weight: 100-143 kg (males); 48-64 kg (females) (3)

horn length: 70-90 cm (males); 20-22 cm (females) (3)

life expectancy in the wild: 15-16 years (males); 22 years (females) (3)

mortality of young: up to 40%

diploid chromosome number: 60 – typical of all Capra species. (1,3)

Daghestan Tur male (left) and female. As in all Capra species anatomical and morphological differences in the sexes are significant. For example males weigh between 100-143 kg, females just around half of that.

With 12 cm or less the Daghestan Tur has the shortest beard of all wild Capra species.

Coloration

Mature male body color, including top of head and tail, is dark brown in winter pelage; front of hind and front legs distinctly darker. Mature males are uniformly dark; rump patch is yellowish and narrow; covered by the tail. In young males, belly and inner-surfaces of front and hindlegs are whitish. Female winter pelage is grayish to sandy-yellow with whitish ventral body and dark brown stripes on front of legs. Summer coat (March to October) of all ages and genders is sandy-yellow (3) to greyish (1), but belly and inner surfaces of legs are dirty-yellow. There are dark brown stripes on frontal surfaces of legs. (3) At least in some specimens there is a dark dorsal stripe. (1)

The grayish or dirty whitish-yellow rump patch is very small and is usually covered by the tail in all age and sex classes. (1)

Horns

The Daghestan Tur exhibits an atypical horn shape. Compared to the horns of other goats which initially grow vertically, the horns of the Dagestan Tur grow in an outward direction then curve inward and then upward. The horns exhibit a smooth, rounded frontal surface with rounded edges. The horn shape most resembles that of the bharal. (7) Some authers call this form „sheeplike“. (4,7) The horns lack transverse ridges. (2) The tips point upward and can be broomed or broken. Horns are triangular in young males and subtriangular to cylindrical in mature males. Basal horn girth in males is 26-30 cm. (3) A single horn sheath can way more than 3 kg. (6) They are larger and heavier than those of the Kuban Tur. (1)

Daghestan Tur male – 15 years and 6 month old. Typical for older males are the upward curved horn tips. Photo taken at Tallinn zoo, Estonia

Approximate position of annual grooves in an old Daghestan Tur male – 15 years and 6 month old. (Not all growth segments in this photo could be located.) According to other Capra species horn growth in Daghestan Tur decelerates with age. Hence distances between annual grooves close to the head are short.

Young Daghestan Tur – 3 years and 9 mounth old. The „upward curve“ of the horn tips has not yet developed. Photo taken at Zoo Liberec, Czech Republic

Young female Daghestan Tur exhibits the female-ibex-typical short, dagger-like horns – although a torsion in the horns is already noticeable.

These horns of an older female show the outward growing curve which is typical for all male Daghestan Tur age classes.

Horn forms of three different Daghestan Tur males. Note that the juveniles show transvers knobs on their frontal horn surfaces which are typical for ibexes, but which disappear in older Daghestan Tur males.

Habitat

Due to the specific relief, climate, and vegetation of the Greater Caucasus, the main Daghestan Tur range areas are on the northern slopes. (1) The Daghestan Tur occurs at elevations of 1000-4000 m in alpine and subalpine open forests, meadows, and river valleys in or adjacent to steep, rocky habitats. Females have a greater affinity to precipitous terrain than males. Most populations spend the year at 2500-3200 m on northern slopes in alpine areas in summer and lower areas on southern slopes in winter. Some populations spend the entire year in open forested areas. In general, males prefer higher, gentler slopes, and open habitats and females use lower, steeper, and open, sparsely forested areas. (3)

Daghestan Turs occur in alpine and subalpine open forests, meadows, and river valleys in or adjacent to steep, rocky habitats. Females have a greater affinity to precipitous terrain than males. Photo taken at Tallinn zoo, Estonia

Mortality

Most mortality is caused by avalanches and predators. Avalanches may account for 60% of annual mortality, mostly of adult males. A succession of severe snowy winters can cause a significant decrease of the population due to drop of birth rates and kid survival. (3)

Predators

Gray Wolves (Canis lupus) can account for up to 20% of the annual mortality,(3) causing the most significant damage to the population. (1) In the Central Caucasus, Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) may account for 58% of kid mortality annually. Large birds of prey can cause 5-7% of annual kid mortality. The Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) is a minor predator. (3) Other predators are leopards (Panthera pardus) and Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos). (1) Mortality from predation is highest in less rugged and steep terrain. (3)

Food and feeding

Daghestan Tur are primarily grazers. Grasses comprise 30% or more of annual diets, but less in summer when forbs become available. Up to 60% of winter diets may consist of browse; they may subsist on pine needles during heavy snow periods. They can use 29-51% of phytomass in a given area, which can alter plant community composition and biomass. They consume mineralized soil and drink from mineral springs. They will paw through snow up to 30 cm deep to reach the underground parts of plants, bend branches with their forelegs, rear up on their hindlegs to reach high forage, and climb slanting trees. (3)

Breeding

Sexual maturity reached: females at age 2, but usually first give birth at age 3 or 4. Males older than 8 years do most of the mating. (3)

male tactics: They guard a single estrous female but will mate with several females during the rut. (3) Fights are extremely fierce and not ritualized. (1)

Mating: lasts 1,5 month from mid-November to the beginning of January

gestation: 165-175 days (3)

parturition: from the end of May until the end of July; with occasional births in August (3)

Young per birth: almost always singletons; only 3,3-3,7% of females twin. (3)

Females squat while urinating – giving males a chance to test ovulation.

„Funky biology“

The mathematics of the Daghestan Tur rut

By counting aggressive interactions or intensitiy of courting between herd members, one can evaluate who’s boss. For example adult males receive 0,2 aggressive interactions from other adult males per hour. Young males receive 0,75 interactions from adult males per hour. The sense behind it: Adult males establish a dominance hierarchy and dominate younger males, attempting to prevent them from mating.

On the other hand, Intensity of courtship in adult males is higher (3,2 displays/hour) than in 3- to 6-year-old males (2,1 displays/hour). Courtship attempts by young males can be aggressive toward females; females responded aggressivly to 15,5% of the courting attempts of young males, but only 9,5% of those by adult males. Males scent-mark during the rut (0,1 mark/hour ) by rubbing bark from tree trunks and bigger branches with their horns, rubbing their post-cornual area on debarked vegetation; they sniff the mark periodically. (3)

Activity patterns

Adult males are least active from 8:00 until 16:00 h. Females are more active during daylight than males, perhaps due to higher nutritional needs in lactating females; they also feed at night. There can be daily vertical movements, to higher elevations in the morning, where they graze in meadows, to lower, rugged terrain in early evening, where they spend the night. This pattern of movements may be reversed in some areas. Daily movements of males are about 1500 m horizontally and 1000 m vertically; those of females are 500 m horizontally and 300 m vertically. (3)

Movements, home range and social organisation

Vertical movements occur seasonally between lower winter ranges and higher summer ranges. Seasonal movements rarely exceed 5 km, but they can be up to 15 km during heavy snows. Males usually move longer distances. Females annual home ranges encompass 4-6 km2. Males have larger home ranges because of their greater movements during the mating season. Adult male groups consistently use the same trails, resting sites, and feeding areas. Population densities vary from 1,5-1,7 ind/ km2 to up to 66 ind/km2 in wintering areas. (3)

Herds have different compositions. Herds for example consist of adult male groups (greater than six years old) with some younger males; younger male groups; female groups that may include young males; and mixed groups consitsting of females and males of serveral ages that include at least one adult male and one adult female. Mixed groups occur during the pre-rut and rutting period only. Adult male mean group size is 12,2. Mean group size of mixed groups is ten animals during high population densities. That of female herds is 6-8. These are the most stable groups. (3)

The kid-female ratio is inversely correlated with population density, ranging from 73 kids:100 females at a density of 1,8 ind/km2 to 48 kids:100 females at a density of 7,3 ind/km2. (3) One explanation for this phenomenon is: The more animals live together, the more stressful life becomes, the less kids are born.

Average annual group size is 7,4 but may change from 5,8 in November-December to 9,5 in May-July. Herds of 300 can be observed in high-density areas. Large herds are temporary groupings, often due to concentrations at artificial salt licks. Group size correlates with population density, ranging from a mean of 11-15 when population density is 1,8 ind/km2 to about 30 at a density of 7,3 ind/km2. In other words: The more animals live in a certain area the bigger are the single herds within that area. (3)

Topography can influence group size more than snow cover, population density, and forested terrain. In a protected area in Ossetia, mean group size was 9,7 in steep terrain and 24 in undulating and less steep terrain. (3)

Herd sizes are negatively correlated with intensity of domestic sheep grazing. In areas without intensive livestock grazing, winter Daghestan Tur density was about 3,1-3,5 ind/km2; it decreased to 1,2-1,5 ind/km2 in rangelands where greater than 80% of the winter pastures of Daghestan Tur were used by domestic sheep. (3)

Conservation Status / threats

IUCN classifies the species as Near Threatened on the Red List. (5) The total number of Daghestan Tur is between 25.000 and 30.000. (1) Others state: Populations decreased from 30.000 in den 1970s to about 20.000 currently; actual numbers are unknown due to lack of monitoring. Most populations are concentrated in small protected areas. (3)

The Daghestan Tur is threatened by competition with lifestock and associated human disturbance, including illegal hunting, inadequate size and number of existing protected areas, and lack of enforcement of wildlife regulations. (3) Furthermore the species is affected by habitat loss and degradation, mineral prospecting, infrastructure projects, especially hydro power-generating dams and plants, armed ethnic conflicts. (1)

Trophy hunting Daghestan Tur

Hunting, including hard currency foreign trophy hunting, is forbidden in Georgia, but is permitted under license in Azerbaijan and Russia. The IUCN suggests in general to consider the possibility of increasing the annual hunting quota. (5)

Azerbaijan

Sustainable use is an integral part of tur protection in Azerbaijan. Currently all hunting is state controlled and local communities gain little or no profit from high cash-value foreign trophy hunting. But local people must receive commensurate economic benefits from hosting hunting tourism. If this is not the case, their attitude fo foreign trophy hunting which should bring outside money for tur conservation will be actively negative and encourage more poaching.

Russian Federation

Trophy hunting takes place, but it is suggested to improve the situation: Better knowledge of Daghestan Tur populations is needed to properly manage local and foreign hunting. Local communities should receive a commensurate part of economic returns from tur trophy hunting to stop poaching.

Georgia

Trophy hunting does currently not take place in Georgia, but community-based trophy hunting has been suggested. Procedures for setting scientific quotas are yet to be developed.

Ecotourism

It is relatively easy for tourists to observe tur in Zakatala Reserce or Kakh Sanctuary, Azerbaijan. Foreign ecotourism could help some protected areas to be nearly self-funding. Local ecotourism will hardly bring any income in the near future. In Georgia tourism is recognised as a threat, although it affects tur to a lesser extent. (1)

Literature Cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.),1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Weinberg, P. 2016. Capra cylindricornis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T3795A91283066. Downloaded on 10 August 2016.

(6) Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern(8)

(7) Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the Pinnacles – Wild Goats of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.