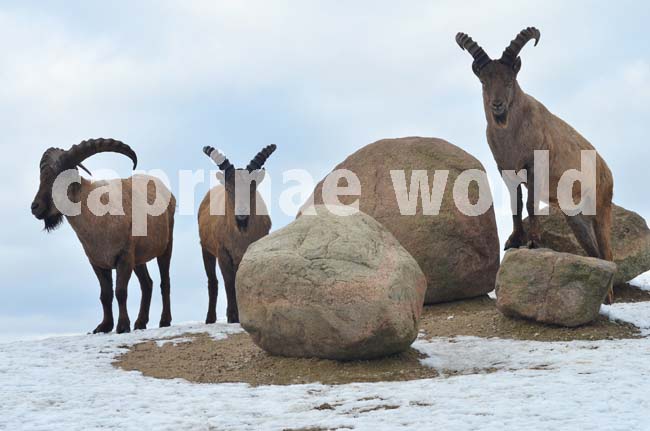

The Kuban Tur is a massivly built ibex. (7) Together with the Dhagestan Tur, Asiatic and Walia ibex, it belongs to the largest Capra species. (4) Of all Capra species it has the smallest range. (3)

Capra severtzovy (left) and Capra cylindricornis have very short, steeply sloping braincases and extremly broad skulls. (4) They both inhabit the Caucasus Mountains.

other scientific names: Capra caucasica (Güldenstädt & Pallas, 1783)

English common names: Kuban Tur, Western (Caucasus) Tur (1); Caucasian Ibex, Severtzov’s Tur, West Caucasian Tur, Western Tur (3); hybrids with Daghestan Tur are Mid-Caucasian Tur (1)

German: Kuban-Tur (3), Westkaukasischer Tur (6), Westkaukasus Tur (1)

French: Bouquetin de Caucase (3), Bouquetin du Caucase occidental (1)

Spanish: Tur del Cáucaso occidental (3), Tur del Caucasus, Tur occidental (1)

Russian: Западнокавказский тур (1)

Abaza: (North Caucasian language): Abg-ab (m), Abg-adzhma (f) (1)

Adyg: (Northwest Caucasian language): k’urshazhe (1)

Georgian: jikhvi (1)

Karachay: (Central Caucasian language): zhugutur (1)

The name „tur“ derives from Russian and Karachay languages meaning Caucasian goat. It is aptly used for both, the western and eastern form. (1) Photo taken at Tallinn zoo, Estonia

Taxonomy

Capra severtzovi (Menzbier 1887)

Type locality: „main Caucasus west of Mt. Elbrus and south of Teberda“

The Kuban Tur is sometimes treated as a polytypic species with the Daghestan Tur (C. cylindricornis) as a subspecies. However, mtDNA data support a strong differentiation of eastern (Daghestan Tur) and western (Kuban Tur) forms congruent with two species. On the other hand morphological and genetic data indicate probable hybridization of Daghestan and Kuban Tur. (3) 9 % of the Kuban-Tur-habitat overlapps with that of the Daghestan Tur. (6) Evidently the two species are closely related. (4)

Distribution / countries occurence

This species inhabits the western third of the Great Caucasus Mountains in Georgia and Russia (4), where it is endemic. (5) It occupies one of the smallest distribution areas of all mountain ungulates. The range encompasses about 4000 km2 and extends west to east for about 250 km. The width of the Kuban Tur distribution range rarely exceeds 30 km. (1) The maximal width is reached near Mt. Elbrus with up to 70 km. (5)

Alpine ibex – 6 ½ years (left) and Kuban tur – 5 years and 9 month old. Note some of the differences in external features: The Kuban Tur is generally lighter in color; has a broader, calf-like scull; thicker horns at the base and a longer beard.

General discription

total length: head-body 159-196 cm (males), 136-164 cm (3)

shoulder height: 90-110 cm (males); 78-90 (females) (3)

weight: 123-155 kg (males); 58-71 kg (females (3)

tail length: 12-17 cm (males); 8-14 cm (females) (3)

horn length: 66-107 cm (males); rarely longer than 30 cm (females) (3)

beard: 12-18 cm, narrow and prominent (3); females occasionally grow beards too. (1)

annual mortality: 10 %

Diploid chromosome number: 60 (3)

Kuban tur, kid and female. Note the black-and-white markings on the legs of the juvenile. These markings are otherwise typical in adults of Nubian- and Walia ibex. Photo taken at Halle zoo, Germany

Coloration

The Kuban Tur has a nearly uniform coat coloration (1) with little contrast. (4) In winter, regardless of age and sex, coloration varies from grayish-brown to dirty-white. Underparts are withish or yellowish-gray. Tail is dark brown, as are the stripes along the front of the legs and the beard in males. The rump patch is small, narrow, and whitish. Summer coats in males and females are brighter, ranging from reddish-gray to reddish-chestnut. (3) The male’s face tends to be darker and browner than the body. (1) There is no dorsal stripe alongside the back. (6,1) The beard of males is rather long (17-18 cm) with the frontal part dark and contrasting with the light remaining part. (1)

12 years and 9 month old Kuban fur. Note the beard with dark hairs in the front and lighter hair towards the neck.

Horns

Male horns grow upward, outward, and then backward in an arc with tips inward or outward. (3) Meile et al. state that the tips „always“ point inward. (6) Horns in cross section are subtriangular, with a broad frontal surface and prominent transverse ridges in the lower portion of the horns, (3) but some specimens exhibit horns devoid of ridges. (7) In general the horns are similar to those of the Alpine ibex. According to the measures presented by Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) horn length of both species appear to be about the same. But some authors state that those of the Kuban Tur are shorter, (1, 4) and more diverging. (4) The girth at base appears to be bigger. (1, 4, 6)

5y9m old Kuban tur male: The broad base of the horns in this specimen and greater divergence are considered to be typical for the species.

12 years and 9 month old Kuban tur male: The horns in this specimen appear to be rather Alpin-Ibex-like.

Two Kuban tur males – 5y9m old (top), 12y9m old. As in many caprinae species horn forms vary a lot within populations or even herds, even if the age of the animals is considered.

Habitat

The Kuban Tur occurs in steep terrain with cliffs and valleys, rocky, broken terrain associated with meadows, and the subalpine and alpine zones at elevations of 1000-3300 m (3) / 800-4000 m (5). The West Caucasus is rather humid, with rainy summers and snowy winters, especially on the southern slopes. Kuban Tur avoid forested areas of spruce and fir, occuring only in sparse pine stands (3,1). They rarely winter on the southern, Georgian slope. (3)

Kuban Turs can be found in the treeless alpine zone. They avoid forested areas of spruce and fir, but do occur in sparse pine stands. Photo taken at Tallinn zoo, Estonia

Surreal looking but actually very species-appropriate habitat of a Kuban Tur at the Tallinn zoo, Estonia.

Predators

In Teberda Nature Reserve and the Caucasus Nature Reserve, Kuban Tur remains were found in 46 % and 23 % respectively of Gray Wolve (Canis lupus) droppings annually. The proportion can rise to 70 % in winter-spring. Annual loss due to wolf predation in Teberda Nature Reserve was about 4 % of the population. (Wolf predation might be higher, because these data were collected during periods of low wolf numbers.) Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx) may prey on females and young. But since their numbers are low, they are no major predators. Large birds of prey occasionally hunt newborn kids. (3) The leopard (Panthera pardus), while formerly a major predator, is now very rare in the Caucasus. (5)

Other mortality factors

In Teberda Nature Reserve, mortality due to poaching rose from 1,4 % in 1986-1990 to 21,6 % in 1996-2000. Avalanches are another mortality factor. In the above mentioned reserves 3 to 6 % of the population were killed. Despite these numbers avalanches are probably not a major mortality factor except in very snowrich winters. (3) Others find that avalanches „cause most natural deaths“. (5)

Grasses comprise 80-90 % of stomach contents in the summer. Note that Kuban Tur females occasionally grow beards.

Food and feeding

Kuban Tur consume over 150 species of plant. Grasses (Bromus, Festuca, Alopecurus, Phleum) are major forage sources. But diets vary annually: Grasses comprise 80-90 % of stomach contents in summer and up to 70 % in winter. Kuban Tur also eat different plant parts in different months. In May and June, they feed on the entire plant. In July and August, they select buds and blossoms, the most nutritious parts. In winter, the animals browse on pine, spruce, and willow. Kuban Turs often visit salt licks, mostly in late spring to beginning of summer. Kids start salt-licking before the age of one month.

Breeding

mating: occurs principally in November-December (3); late november-early january (1)

males delay mating: until 6 years of age (3,1)

male tactics: defend a single estrous female and prevent other males from mating with the guarded female. (3); mature males fight aggressivly. (1)

first young for females: at age 3 or 4 (3)

gestation: 165-175 days (3); 150-160 days (1)

time of births: May and June, but births occur as late as August (3)

number of young born: usually a single, rarely two

Activity patterns

In winter, Kuban Tur usually feed during the day, with peaks at 5-11 and 17-19. In summer, there are feeding peaks at 3-9 and 15-21. Kuban Tur become highly nocturnal when hunted or if they have to share pastures with livestock. During harsh weather, they seek shelter in overhanging cliffs and rock outcrops. (3)

Movements, home range and social organisation

Kuban Turs can be highly gregarious, with herds of 100-300 individuals in high-density populations. In populations of several thousands, herds usually have 11-20 animals. Individuals may interchange between herds. Some herds move 10-12 km (3) and up to 20 km (1) from one mountain to another. Population densities are 3-6 ind/km2 in populations of 1300-2700 animals. In the early 1960s, when there were 12.000 Kuban Tur in the Caucasus Nature Reserve, winter habitat consisted of about one-third of the summer habitat above timberline in the reserve; consequently the population density was greater than 44 ind/km2 in winter and 13 ind/km2 in summer habitat. (3)

Daily movements between feeding and resting areas are particularly distinct on southern slopes, which are exposed to high amounts of solar exposure. During summer, these movements are driven mainly by the effects of temperature. During the hottest part of the day, they shelter in the shade of cliffs or under trees, and will even lie in snow if available. In forests, tur will choose ravines where a steady breeze blows, while in the cooler temperatures of high altitudes they may lie out in the open. In cloudy weather or on rainy days, they may be seen foraging in the open throughout the day. In areas of high human activity tur emerge to graze only after dusk, returning to cover at dawn. (1)

How the Kuban Tur could have emerged

The Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) once ranged up to the West Caucasus. The Caucasian population became isolated there by climatic change, perhaps being several times cut off and then rejoined in successive glacial/interglacial cycles, and its genome was periodically swamped by the larger C. cylindricornis males dominating the smaller C. ibex males. Males formed a fittness series: cylindricornis > hybrids > ibex. In this scenario the Kuban Tur represents a stabilized hybrid population, with the west end retaining more C. ibex characters than the east end. The present situation would be the latest cycle, with C. cylindricornis genes again introgressing the West population. We suggest that the two Caucasian forms have to hybridize, because, in occupying much the same altitudinal range, they must compete. (4)

Conservation Status / threats

The IUCN classifies the Kuban Tur as „endangered“ because of a serious population decline, estimated to be more than 50 % over the last three generations. (5) The Kuban Tur is protected in several nature reserves and national parks, but their numbers on the southern slope of the Main Range in Georgia are mimimal. Despite listings in regional red data books and occuring in a number of protected areas, Kuban Tur underwent a considerable, and even catastrophic, decline in the late 1980-1990s due to uncontrolled hunting. For example in Caucasus Nature Reserve numbers declined from 10.000-12.000 in the first half of the 1970s to about 3000. (3) Data from 2001 state 2500 animals for this area. (1)

Kuban Tur numbers outside protected areas are low, even minimal. Currently there is a total of about 5000-6000 Kuban Tur. (5, 3,1)

Major threats encompass poaching and lax enforcement of game laws, competition with lifestock and human disturbance. (3) Other threats are mineral prospecting, dam building, tourism, civil strife and habitat loss. (1)

There is an urgent need for additional protected areas with adequately trained personnel to monitor populations and prevent poaching. (3) The most useful conservation measure at present would be to increase the level and effectiveness of protection in existing reserves, because organziation of new ones seems improbable for the time being. (5)

Trophy hunting Kuban Tur

In the Russian Ferderation Kuban Tur hunting, including hard-currency-earing trophy hunting, is permitted under license. The hunting season runs from August 1 to November 10.

In Georgia the Kuban Tur is critically endagered. It numbered 2500 animals in 1996. The status today is unknown. Hunting is presently prohibited, but poaching for subsistence and trophies remain a problem. Tur hunting is part of the cultural life and viewed as a matter of personal valor. Hunters are deeply respected in the local society. It is therefore suggested to establish community-based trophy hunting, upholding the precepts of traditional hunting. (1)

Literature Cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Weinberg, P. 2008. Capra caucasica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3794A10088217. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3794A10088217.en. Downloaded on 02 August 2016.

(6) Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern

(7) Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the Pinnacles – Wild Goats of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.