The Mountain Goat is endemic to the mountainous regions of Western Canada and the Northwestern United States. [1]

Names

English common names: American Mountain Goat [1], Rocky Mountain Goat, Mountain Goat, Snow Goat, White Goat [3],

French: Chèvre des Rocheuses [3], Chèvre des Montagnes Rocheuses [5]

German: Schneeziege [3],

Russian: Снежная коза [1, Wikipedia]

Spanish: Cabra blanca de las montañas rocosas [1], Cabra blanca [5] Cabra blanca de las Rocosas [3],

indigenous languages – Cree: Mathateke, Dogrip: Sahzhoa, Navajo: Tse-Ta-Dz [5]

name derivation: Oreamnos derives from the Greek words Oreos, for mountain, and amnos, for lamb. [1]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

Oreamnos americanus americanus, [Antilope (Rupicapra) americana], Blainville 1816, Bull. Soc. Philom. p. 80. Type locality Cascade Mountains, near Brant Island, Columbia Valley, Oregon [1]

Oreamnos americanus kennedyi, Elliot 1900 [1]

Oreamnos americanus missoulae, Allen 1904 [1]

Oreamnos americanus columbianus, Elliot 1905 [1]

Taxonomy

The Mountain Goat, despite its name, is not a true goat and is more closely allied with the chamois and gorals than the genus Capra. There is disagreement about the phylogenetic position of Oreamnos (Hassanin et al. 1998). Some studies based on molecular and morphological characteristics place the Mountain Goat close to wild sheep (Gatesy et al. 1997). Traditionally many taxonomists classified Oreamnos americanus as belonging to the tripe Rupicaprini, or goat-antilopes, which, in addition to the Mountain Goat, includes the Serows, Gorals and Chamois. However, while Serows and Gorals are related to each other, they are not related to the Mountain Goat or Chamois, and Mountain Goat and Chamois are also not related to each other (Hassanin et al. 2009) [1]

Mountain Goat hides were acquired by Captain Cook as early as the late 1700s, but Cook had presumed that the hides were from white bears. [1] Photo: Bürglin

Subspecies

Dolan (1963) discussed the validity of the described subspecies, recognizing only O. a. kennedyi as different from O. a. americanus, distinguished mainly by its larger size, constricted forehead in front of the horn bases, and perhaps more outwardly curved horns. [4] Cowan and McCrory (1970) recognized no subspecies, since the geographic variations, particularly between specimens from northern and southern populations, have not reached a point where taxonomic recognition as a subspecies can be justified. [1] Groves and Grubb (2011) take no position on the existence of subspecies, but note that further study is needed. [4]

Distribution

Canada, West: Yukon, Northwest Territories, British Columbia and Alberta [1, 3]

USA, West: Southeast Alaska, Washington, Montana and Idaho

Introduced – into several US states: Alaska – Kodiak, Chichagof, Baranof Islands [1, 3] and Revillagigedo and some smaller islands off the Alaskan coast [1]; Washington (Olympic Peninsula), Oregon, Central and South Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota (Black Hills), Colorado, Utah, Nevada. [2, 3]

(Possibly) former occurrences: A number of historical documents published during the 1800s place Mountain Goats in Oregon and California, and in historical times the species may have occurred at least as far south as the Central Cascades and the northeast mountains of Oregon (Matthews and Heath 2006). [1]

In Canada, mountain goats inhabit all major mountain ranges from the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains in Alberta, west to the Coastal Range of British Columbia, and north into the St. Elias, Coast, Cassiar, Logan and Selwyn Ranges of Yukon; and the Mackenzie Mountains of the Northwest Territories.

In Alaska, the mountain goat is generally continuously distributed along the mountains extending up the west coast to Prince William Sound and the Kenai Peninsula. It also occurs in the southern Wrangell and Talkeetna Mountains and the northern Chugach Mountains. [2]

Exclusiveness of distribution: In certain areas, they share their habitat with mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis and O. dalli), but in areas with heavy snow, such as the coastal regions, they are the sole large mountain ungulate. [1]

General description

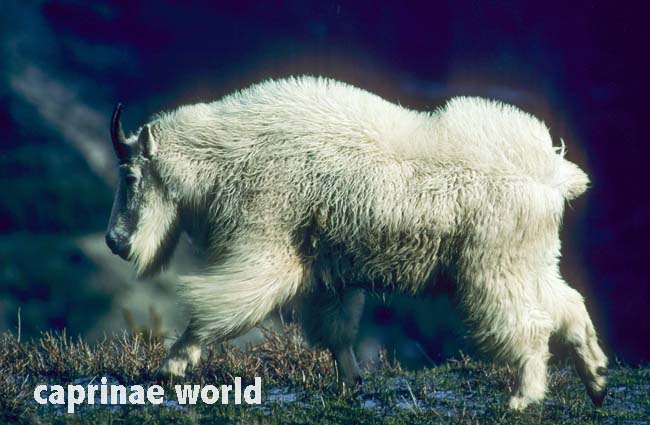

body: stocky, blunt [1], bear like [5], with a high-shouldered profile, supported by short [1] muscular legs [5]

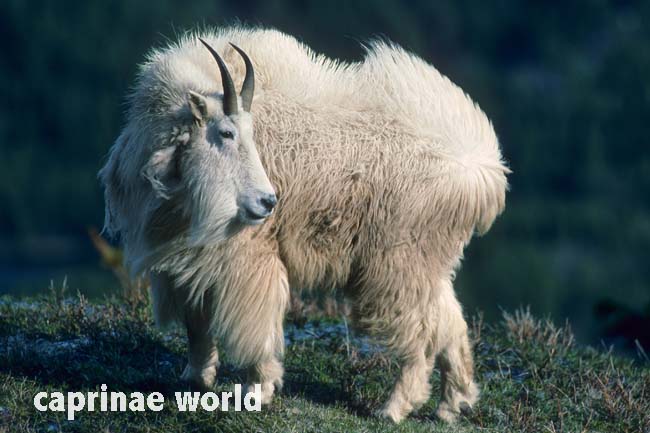

Nanny displaying a high-shouldered profile – enhanced through elongated hair in the shoulder region. Photo: Bürglin

Mountain Goats have also elongated hair along the lower spine – comparable to Chamois. Photo: Bürglin

length / head-body: males (billy) 155-180 cm, females (nanny) 140-170 cm.

shoulder height: 90-110 cm [3]; around 95 cm [1]

weight: males 95-115 kg, females 60-75 kg [1, 3]; females attain peak mass at age six, but males continue to gain mass with age. [3]

head: narrow; compared to the heavy scull of wild sheep, the head of Mountain Goat is light and fragile. [1]

glands: black supra-occipital glands (located just behind the horns); more developed in billies; swollen during the rut; thought to be used for scent marking during the rutting season. [1]

hooves: oval; larger than those of mountain sheep; with large interdigital clefts and prominent dew claws; has a slightly convex and pliable pad that extends beyond the outer cornified shell [1]teats: four, whereas sheep and true goats have only two [1]

tail: 10-20 cm [3]; 8,4-20,3 cm [1]

sex determining in the field: 1. Males are bigger, but there is discord regarding the magnitude: Rideout and Hoffmann (1975) write that males exceed females in linear measurements by 10 to 30 percent [1], others state that males are even 40 to 60 percent larger than females [3]. Otherwise the horn base rule (2., see below) helps to differentiate the sexes. There is three more criteria: 3. the vulvar patch in females, 4. the urination posture – females squat, whereas males stretch – and 5. the group composition: Lone adults and those in groups of two or three, with no accompanying kids or yearlings, are usually billies. If the group contains kids, the adults are almost certainly nannies, unless it’s the mating season. [1] Nonetheless, differentiating males and females in the wild remains difficult. [3]

diploid chromosome numbers: 42 [1, 3, 4]

lifespan in the wild: 15 years for males, 18 years for females. [3] But very few males live longer than 10 years. Very few females survive more than 16 years (Festa-Bianchet and Côté 2008). [1]

Horns

Horns of Mountain Goats are black [1, 5], smooth, pointed, conical and slightly curved posteriorly. [1]

Horns are said to be black. But bases of horns can be also brown-coloured as in this young billy. Photo: Bürglin

Horn length is 21-30 cm. [3] The largest trophy listed in the 12th edition of Boone and Crocket Club Records of North American Big Game was harvested in the Babine Mountains of British Columbia in 1947. Both horns are 30,5 cm long, with a basal circumference of 16,5 cm, and a spread of 22,9 cm. Almost all of the goats with the heaviest and longest horns come from either Alaska or British Columbia. [1]

Horns of females have slimmer, straighter horns, that are less divergent at the tips. [5] The tips of female horns appear to be rather angled.

Horns of males are slightly longer. It is assumed that this is due to their longer first increment. [1] The transition from the base of the male horn to the tip is more an even arc. Males have thicker horns than females at all ages, absolutely and relative to body size. [1] The basal girth in males is 11 to 16 cm. [3]

Male with typical horns. Diameter of horns at base is bigger than the diameter of the eyes. Photo: Bürglin

male and female horns in comparison: B. L. Smith (1988) reported average horn lengths of 23,2 cm in adult males and 22,2 cm in adult females from Idaho and Montana (Festa Bianchet and Côté 2008). [1] However, since the difference in horn lengths between males and females is not very distinct, unsurprisingly other authors write that female horn length can equal those of males. [3] Furthermore adult males often have shorter horns than females for a given body size. During the first two years of life, billies put on more horn growth than nannies (16,6 vs. 14,7 cm). On the other hand the reverse situation was documented for the third year of life, when females grow a larger increment than males (4,4 vs. 3,4 cm). [1]

horn base rule to determine sex: In nannies horn base circumference is about the size of the eye in females, whereas horn base circumference in males is much bigger than their eye. [1]

determining age: The passage of each winter is recorded in the horns in the form of annuli (groth rings or better: grooves). During the first winter there is no cessation of growth. Therefore the first distinct annual growth ring is formed at the beginning of the second winter, when the goat is about 1,5 years old. Thereafter, each subsequent ring is formed in early winter. Hence, the age can be estimated by adding one year to the number of distinct rings counted. But only the first seven to eight annuli can normally be measured because later growth rings are often indistinct (Brandborg 1950). The sulcus formation (groove) after 1,5 years suggests that the cessation of horn growth is more a matter of hormonal influence than food shortage. [1]

An increase in basal circumference and tip-to-tip spread occurs with each annual growth in horn length (Cowan and McCrory 1970), but the annual horn increments become smaller with increasing age in both sexes. [1] Photo: Bürglin

horns as weapons: The horn curvature of the upper third of the horn length in male or female Mountain Goats never reaches the degree of curvature seen in Chamois. Mountain Goat horns, therefore, are very effective attacking weapons. [1]

Pelage / colour

Pelage consists of white wool and hollow guard hair, often with some scattered dark brown hairs on the back and rump (Seton 1929), providing insulation and camouflage for living in cold climate with persistent snow. [1]

Billy in spring: The coarse guard hairs can reach lengths of more than 20 cm [1], especially on cheeks, legs, shoulders and lower spine. Photo: Bürglin

winter: Males and females have a dense, shaggy [5], uniformly white [3] / yellowish [2], long pelage with a prominent mid-dorsal mane. [3] The yellowish hue appears especially shortly before the coat is being shed in spring. [1]

summer: white and woolly [5], sometimes dirty brown [6]

molting: The molt in spring makes animals look extremely ragged. [5] The exact time of shedding depends on locality, sex, age, condition and reproductive status. Molting is completed by early August and the new, short coat provides relief from the summer heat. [1]

Trails that are regularly used in spring between salt licks and resting spots are well marked with lost hair that remains sticking to twigs and branches. Photo: Bürglin

Collecting wool: It is said that indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest incorporated Mountain Goat hair into their weaving by collecting spring moulted wool left by wild goats. [Wikipedia]. Photo: Bürglin

beard: in adult animals – males and females [3], but more prominent in males. The beard grows with age to about 10 to 13 cm in length. [1]

eyes and nose: black, contrasting with the otherwise white face [1, 3]

Similar species

The only other North American Bovid with white pelage is the Dall’s Sheep (Ovis dalli), which has large spiral horns. Mountain Goats may be confused with ewes of Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis). Sheep can usually be distinguished by their brown coat and tan-coloured horns [5], but the pelage of Mountain Goats can appear brownish as well.

Five Bighorn Sheep (lying) and three Mountain Goats standing in the background during spring time in Glacier National Park, Montana. Apparently at this time of the year the two species are hard to tell apart from a distance. The coat of the Mountain Goats is only slightly lighter. Photo: Bürglin

Ancestry

The Mountain Goat decends from an Ice Age rupicaprid that crossed the Bering land bridge from Asia, where goat-antilopes as Goral and Serow dwell today. During the last major glacial advance (Wisconsin), an ancestral Mountain Goat lived at least as far south as Northern Mexico. Until about 12.000 years ago, two species of Mountain Goat were present in the Southwestern United States, O. americanus and the smaller O. harringtoni. But when the ice sheets receded, harringtoni became extinct and americanus moved back north. [1]

Habitat

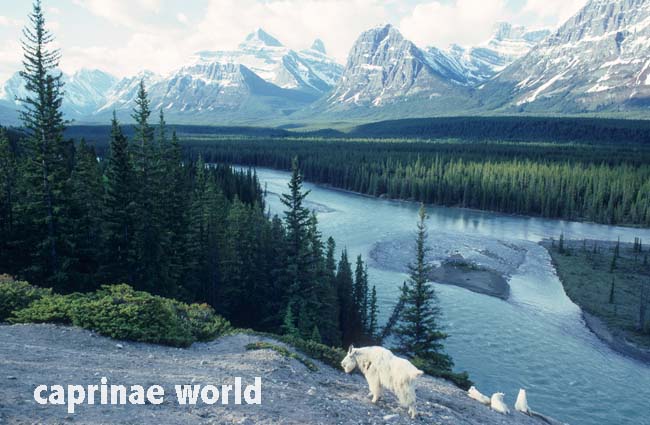

The Mountain Goat is primarily an alpine and subalpine species, but in coastal areas it sometimes descends to sea level. Throughout the year, the animals usually stay above the timberline, but they will migrate seasonally to higher or lower elevations within that range. [2] They usually occur in rugged, precipitous terrain to above 2700 metres. Habitats consist of a mosaic of forage-rich alpine meadows, timbered areas, high-mountain ridges, scree, and barren cliffs that provide escape terrain, especially for females with young. [3]

This Mountain Goat was witnessed shaping it’s habitat by uncovering roots while searching for minerals. Undoubtly this led to toppling over the tree. Photo: Bürglin / Jasper Lake, Jasper National Park.

These nannies even act as sculptors while digging for minerals. Photo: Bürglin / Kirkeslin Mountain Lookout, Jasper National Park.

During winter, they use areas within 300 to 500 metres of escape terrain. Some populations do not make altitudinal movements. [3]

sex-specific habitat use: Following the rut, females use more rugged, steeper terrain than males and stay closer to escape terrain. Nursery groups in summer use habitats from the tree line to higher vegetation, and in winter are found near the tree line and slightly below it on snow-free south and west-facing slopes. [3]

Solitary males and male groups can remain in forested areas near the tree line throughout the year. [3] Photo: Bürglin

colonisation: Mountain Goats can move across inhospitable habitat to an unoccupied area of suitable habitat temporarily using small, isolated patches of landscape. [3]

Mortality / Predators

Predation is probably the most significant mortality factor. Major predators include Cougars (Puma concolor), Grey Wolves (Canis lupus), Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) [2, 3], and occasionally Coyotes (Canis latrans), Black Bears (Ursus americanus), Wolverines (Gulo gulo), and Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos). [3]

Food and feeding

Mountain Goats have very broad food tolerances and eat almost any forage. [1]. They are mainly graminivorous (grass feeding), but food habits vary also seasonally. Based on food habits throughout their range, summer diet consists of 52 per cent grasses, 30 per cent forbs, and 16 per cent browse. Winter diet is 60 per cent grasses, 8 per cent forbs, and 32 per cent browse. Browsing, including conifers, takes a greater significance during winter. [3]

Plants that are eaten by Mountain Goats include herbs, sedges, ferns, moss, lichen, twigs, and leaves from low-growing shrubs and conifers. [2] Where goats inhabit forests to escape deep snow or excessive heat, arboreal lichens are preferred forage (Smith 1976). [1]

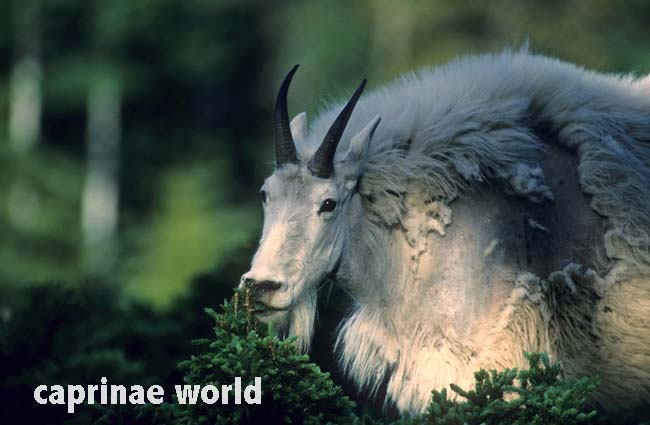

Increased conifer consumption, particularly firs, seems to be associated with severe winter conditions (Geist 1971) [1]. Photo: Bürglin

Breeding

mating season: peaks in November-December [3]

mating behaviour: Only during the rut are adult males dominant over adult females. At other times of the year, adult females are dominant over all age and sex classes. Dominant males probably guard an individual female from other males when the female is in estrus. [3] Rutting billies mark vegetation with horn glands, dig rutting pits, and use their front feet to toss urine soaked soil against their bodies. [1] Fights between rivalling males are extremely violent, often causing serious injury or death. [5] In old males, the skin may be as thick as 2,2 cm in places (Geist 1964, 1967). Geist (1967) suggested that these dermal shields were an adaption to the high risk or injury caused by the goat’s typical antiparallel circular maneuvers while fighting. [1]

first year of parturition: Females in an established population in Caw Ridge, Canada, first give birth at four or five years of age. But Mountain Goats attain mass at a slower pace than other ungulates, reaching peak kid production at eight to twelve years. Most yearlings are the offspring of females eight to twelve years of age. [3]

gestation: approximately 180 days [1], 185-195 days [3]

lambing season: May-June [3]

Prior to parturition, females seperate from female groups to give birth [3] to later join them again. Photo: Bürglin

Twins are common in places, where Mountain Goats have been introduced recently – probably because infraspecific competion is low and predators have not yet adjusted. Photo: Bürglin

parturition sites: Nannies utilize the least accessible and most secure crannies. [1]

nursery groups: Nannies with kids form nursery groups. These groups can reach 100 individuals, but rarely exceed 30 animals by late autumn and winter.

kid survival: On average at Caw Ridge, 87 percent of kids survived to weaning age and 64 percent suvived to one year of age. Kid survival ranged from 38 percent to 92 percent. Survival to two years was 73,5 percent for yearling males and 84,7 percent for yearling females. After the age of eight, adult females experienced higher survival rates than males. Over 50 percent of yearling females and less than 10 percent of yearling males survived to ten years. Survival of females two to seven years of age was 94 percent. [3]

Activity patterns

In summer, Mountain Goats are most active during the cooler periods of early morning and late afternoon but also have activity periods during the night. They usually have six to seven feeding-resting cycles throughout the day. [3] Mountain Goats are relatively slow-moving, sedentary animals, for the most part, but they are also renowned for their exceptional speed and agility on steep terrain. They have been observed quickly seeking shelter from cold heavy rain and wet snow – apparently because their coat is not very water repellent. [1]

Aggressivness towards humans: Mountain goats can occasionally be aggressive towards men, with at least one reported fatality resulting from an attack by a mountain goat. [7]

The author of this chapter and two assistants were threatened by this single billy, while researching on Mountain Goats during springtime in Glacier National Park, Montana. The billy approached slowly, while horning the vegetation. Hiding behind a bush made the goat leave the area. Photo: Bürglin

Movements, home range and social organisation

Male and female groups are spatially segregated except during the mating season. Adult females are highly aggressive and form linear hierarchies.

Typical fighting posture: Two nannies circling antiparallel in a mutual present-threat. Photo: Bürglin

Males can be solitary or form bachelor goups. [3] During the warmer months, groups of less than four animals are normal; adult males are frequently solitary. However, during the winter, groups may join to form larger herds. [1]

social status: Horn size, body mass, and body size are not related to social status; age is the most important factor. [3]

home ranges: Males have larger home ranges than females during the rut but smaller home range during summer. Differences in home ranges are probably due to topography and proximity to neighbouring groups during the rut. [3] Home ranges average about 23 km2. [1]

seasonal shifts in elevation: Summertime migrations to low-elevation mineral licks often take them several or more kilometers through forested areas. [2] In east-central British-Columbia, some Mountain Goats used separate winter and summer ranges 8 to 13 km apart. In winter, they often used southerly aspects at lower elevations in commercial forest stands. They used high-elevation licks that were within their home range or 6 to 14 km from their typical home range. In coastal Alaska, where goats selected elevations at 300 to 1200 metres, females moved 0,9 to 5,5 km along valleys during the winter; males moved 1,4 to 4,3 km. Annual movements of females ranges from 2 km to 6 km and those of males varied from 3 km to 10 km. [3]

Salt licks are very important features in the habitat of Mountain Goats, that determine the goats movements within their habitat. Photo: Bürglin

daily shifts in elevation: The goats were found at lower elevations from evening to dawn more often than they were during the day. [3]

Mean winter home range size was 1,4 km2 for females and 2,7 km2 for males and included burned timbered areas. 42 percent of males use was in mature or old forest (greater than 80 years old) compared to 29 percent for females. Males and females made less use of young forest (less than 40 years old) and used slopes between 41° and 60° and up to 70° for females. [3]

nursery groups movements: Females with kids and 1-2-year-olds make longer daily movements than bachelor groups or solitary males. Male home range encompasses 6,3-21,5 km2 and those of females are 8,9 to 25 km2. [3]

Population

total population: 80.000-119.000 animals [2]; 75.000-110.000 [3]

In Canada, the total population is approximately 58.000 individuals, but could range from 44.000 to 72.000, distributed as follows: Alberta 2.750; British Columbia 39.000-67.000; Northwest Territories 1.000; and Yukon 1.400.

In the United States total estimates are 36.000 to 47.000 individuals, with more than 12,000 animals in the contiguous states, and 24,000 to over than 33,000 in Alaska. [2]

Conservation Status / threats

According to IUCN the Mountain Goat is listet as „Least Concern“. The species is largely protected from threats due to the inaccessible nature of their habitat. [2]

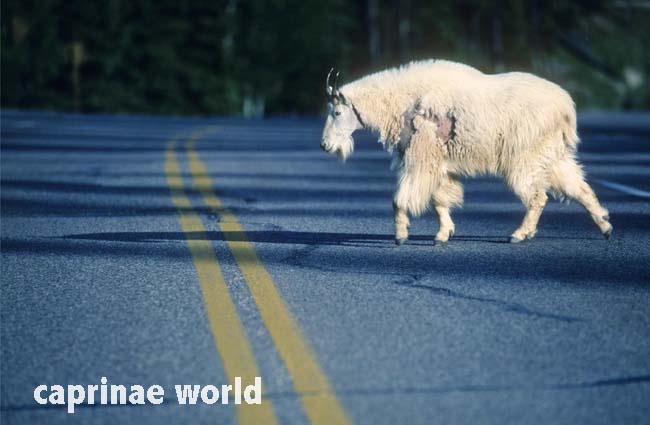

Nevertheless Mountain Goats are more sensitive to human disturbance than most other ungulates [2] and outside protected areas they are vulnerable to human disturbance like unregulated tourist activities [3]. Mountain Goats are particularly sensitive to harassment from aircraft. [2] Other concerns are habitat destruction resulting from mineral and oil and gas exploration and extraction and clear-cutting forestry practices. Habitat fragmentation is a further concern due to road construction and other developments. Introduction of Mountain Goats into areas not historically occupied should be done with caution, because they can cause degradation to alpine environments. [3]

Protected areas: In Canada, mountain goat habitat, along with more than 3,500 goats, are protected in eight National Parks (Banff, Glacier, Jasper, Kootenay, Nahanni, Revelstoke, Waterton and Yoho), Kluane National Park Reserve, and in Kluane Wildlife Sanctuary. Numerous provincial parks and wildlife reserves throughout western and northern Canada provide additional varying levels of protection. [2]

Transplants have been used to reintroduce mountain goats into many areas of its former range. Habitat management continues to play a key role in its conservation, and developments are subject to environmental screening processes on public land. Conservation measures proposed for Canada: 1) Determine the species’ requirements for mature forests on steep slopes in coastal mountain ranges that are used as winter habitat in British Columbia (Hebert and Turnbull, 1977; Fox et al., 1989). Several coastal populations will be affected by current and future timber harvest operations. Ideally, much or most of this habitat should be preserved. 2) Obtain more accurate population inventories in all regions of Canada to allow more detailed management plans to be developed. [2]

In the United States, primary conservation measures have included habitat protection, introductions and re-introductions, and harvest regulation. Eight state wildlife management departments have transplanted mountain goats from native ranges in Canada and the United States. Six of these states did not have indigenous populations. Many transplanted populations were established with only 10 to 15 founder animals. The mountain goat occurs in nine federal protected areas: Alaska: Glacier Bay, Kenai Fjords, and Wrangell – St. Elias National Parks; and Kenai National Wildlife Refuge; Montana: Bison Range National Wildlife Refuge; Glacier National Park; South Dakota: Mount Rushmore National Monument; Washington: North Cascades, and Mount Rainier National Parks. However, most herds are in national forests including many wilderness areas). The International Order of Rocky Mountain Goats ((http://www.rockymountaingoats.org)), a private organization, raises funds for research and management of the species. [2]

Trophy hunting

Hunting is well managed in both range states, which has stabilized past declines.

Legal hunts are under strict controls issued by provincial or territorial government agencies. [2] This is necessary because Mountain Goat populations are particularly sensitive to indiscriminate age and gender hunting. [3] The management for recreational hunting is also challenging because different populations appear to have radically different reactions to the harvest regimes in use. [1] So a conservative management strategy is required. [3]

Sustainable harvest rates for small native populations are greatly influenced by the selection, in terms of sex and age, of harvested animals (Hamel et al. 2006). Specifically, the harvest of even 1 to 2 percent of female goats of reproductive age (4 to 9 years old) can adversely affect small populations (Hamel et al. 2006). In consequence, natural goat populations may be unable to sustain a total yearly harvest greater than 2 to 3 percent (K. G. Smith 1988). Generally, populations of less than 50 individuals should not be disturbed. [1]

In contrast to established native herds, many introduced herds show several years of rapid growth with high twinning rates, expecially when range conditions are good and predators absent. These herds are generally much more productive than native herds and can tolerate much higher harvest levels, through compensatory reproduction, following artificial reductions. Sustainable harvest rates for introduced populations were estimated to range between 7 and 15 percent (Williams 1999). [1]

Harvests are set annually for each population. In British Columbia for example, harvest rates vary between populations and range from 0.4 to 9 percent (Hebert and Smith, 1986), with an average of 1.100 to 1.200 goats shot by resident and non-residents each year in the Province. In Yukon, by contrast, harvests are much lower, varying between 3 and 15 animals per year, with the aboriginal harvest estimated to be zero. [2]

In the US Mountain Goats are harvested in nine states under conservative regulations of the wildlife departments which monitor populations. One state, Colorado, uses two hunting licenses in an auction and a raffle to raise funds for research and management of the species. [2]

Hunting by aboriginal people

First nations hunting is permitted in some northern national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, and licensed hunting is permitted in many provincial parks. However in Yukon, the aboriginal harvest was estimated to be zero. [2]

Nuxalk men, and Southern Kwakiutl speared or snared Mountain Goats, which they hunted with dogs. They valued the goats for fleece and horn as well as meat. [9]

„Training“ of dogs: Mountain Goat hunters living on mainland inlets described to anthropologist Philip Drucker how well-trained dogs could drive goats into isolated mountain pockets, where hunters could kill them. The „training“ they referred to consisted of ritual, such as once a day, for four days, pressing a warmed, right forefoot, cut from a kid [Mountain Goat?], against the feet of a puppy. This was believed to give the pup sure-footedness like that of goats themselves. Such a dog was said to climb above a band of goats and turn them downhill towards human hunting parties. [9]

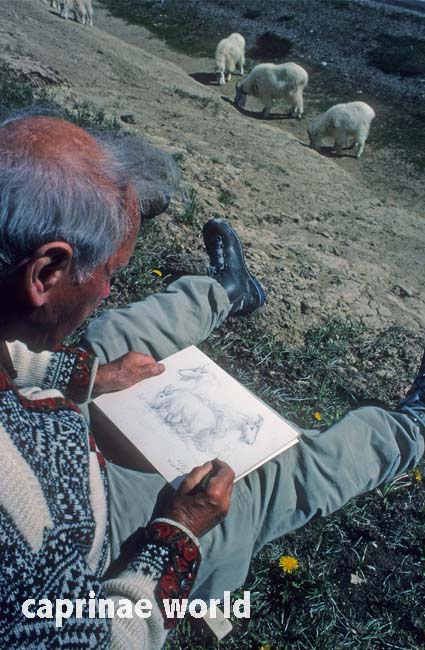

Ecotourism

Mountain Goats belong to the Northamerican Megafauna and are highly esteemed by visitors. They are also easily observable. Listed below are some viewing opportunities:

- Alberta, Jasper National Park, Kirkeslin Lookout (here the Icefields Parkway cuts through mineral-rich deposits, where Mountain Goats lick and dig for salt in spring), 38 km southeast of Jasper [8]

- Alberta, Jasper National Park, at the northern end of Jasper Lake, where Highway 16 cuts a ridge

- Yukon, Mount White in Agay Mene Territorial Park. [6]

- Yukon, peaks of the Coast Mountains along the South Klondike Highway at the B.C./Yukon border. [6]

- Yukon, St. Elias Trail in Kluane National Park, and Goatherd Mountain, which looms over the Lowell glacier. [6]

- Montana, Glacier National Park, southern boundary, along Highway Nr. 2, 5 km east of the Walton Ranger Station [8]

Full description of the species

Rideout and Hoffmann (1975)

Literature Cited

[1] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

[2] Festa-Bianchet, M. 2008. Oreamnos americanus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T42680A10727959. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T42680A10727959.en. Downloaded on 08 May 2018.

[3] Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

[5] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princton University Press.

[6] http://www.env.gov.yk.ca/animals-habitat/mammals/goat.php#people

[7] https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/mountain-goat-kills-man-in-olympic-national-park/

[8] Gadd, Ben, 1995: Handbook of the Canadian Rockies. Corax Press, Jasper, Canada

[9] Kirk, Ruth, 1988: Wisdom of the Elders – Native Traditions on the Northwest Coast. The Nuu-chah-nulth, Southern Kwakiutl and Nuxalk. The Royal British Columbia Museum, Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver/Toronto