The Muskox is the largest herbivore of the Arctic. It has a circumpolar distribution range and even inhabits the northernmost land on the globe.

Names

English: Muskox [16], Musk Oxen [2]

French: bœuf musqué [Wikipedia], Boeuf-musqué [16], Boeuf musque [2]

German: Moschusochse [2, 16]

Greenland Inuktitut: Umimmak [2]

Greenland (Danish): Moskusokse [2]

Nanuvut Inuktitut: Oomingmaq [2]

Russian: мускусный бык, Овцебык [2, Wikipedia]

Spanish: Buey amizclero [2, 16]

Ovis (Latin, a sheep), bos (Latin, an ox), and moschatus (Latin for musky) form the basis of the generic name. Zimmermann’s original description, Bos moschatus, is based on accounts by the French officer Jérémie, who was stationed on the west coast of Hudson Bay from 1697 to 1714.

Jérémie referred to the animal as boeuf musquez (editor’s note: or mosqué?), describing it as a kind of cattle smelling strongly of musk (Allen 1913). However, Musk Oxen do not possess musk glands, they do not ooze a musky smelling liquid from preorbital glands and they are not cattle or oxen. [2] Hence the name is completely misleading. [7]

The vernacular name „muskox“ may either be an Anglicised version of Jérémie’s boeuf musqué or, as Wilkinson (1971) suggests, derive from the Ojibwa-Indian word muskeg, which describes some of the habitat where the species is found. [2]

The Inuit name for the species is oomingmak (various spellings are possible), which means „the bearded one“, a good description of the long-haired muskox. [2]

Taxonomy

Ovibos moschatus Zimmermann, 1780, Hudson Bay [4]

The Musk Ox (Ovibos) evolved in the late Pliocene or early ice age (Pleistocene) [10] in Asia and spread to North America circa 90.000 years ago. [16]. Today it occupies only a vestige of its former range, which once extended from England to Siberia and over North America as far south as new York and Iowa. Several extinct muskox genera, such as Bootherium and Symbos, also lived during the Pleistocene (Tener, 1965). [10]

Anatomical, chromosomal and blood studies indicate that the Muskox is more related to sheep and goat than to cattle. [5] Muskoxen (Ovibos) and Takins (Budorcas) were formerly considered closely related and classified in the tribe Ovibovini, but Muskoxen, based on mitochondrial DNA alalysis, have a closer genetic relationship to Gorals (Nemorhaedus) and Serows (Capricornis) than to other genera of the tribe Caprini. Monotypic. [16]

Diploid chromosome number: 48 [2], 52 [16] – contradicting!

Other putative scientific names

Bos moschatus, Zimmermann, 1780, Hudson Bay [4]

Bos moschatus, Zimmermann, 1780, Canada (Manitoba, between Seal and Churchill rivers [16]

Ovibos moschatus platycerus, Fischer von Waldheim, 1814 [2]

Ovibos moschatus peary, Allen, 1901 [2]

Ovibos moschatus wardi Lydekker, 1900 [4]

Ovibos moschatus wardi Lydekker, 1905 [2]

Ovibos moschatus niphoecus Elliot, 1905 [4]

Ovibos moschatus mackenzianus Kowarzik, Great Slave Lake, 1910 [4]

Ovibos moschatus mackenzianus Kowarzik, 1908 [2]

Ovibos moschatus melvillensis Kowarzik, 1910 [4]

Ovibos moschatus melvillensis Kowarzik, 1909 [2]

Subspecies

Several authors argue in support of not recognising any subspecies [4, 5, 6, 16].

For example control-region sequences of mitochondrial DNA comparisons between muskox populations reveal only small differences and do not support recognition of subspecies. Muskoxen do not even exhibit a latitudinal or climatic trend in body size. [16]

Groves and Grubb (2011) also speak out in favour of a single valid species in stating: J. A. Allen’s (1913) monograph, while thorough and remarkably detailed, is not convincing about geographic variation. For example, in his table of measurements, the range of variation of 16 skulls less than 8 years of age from North Grant Land (on Ellesmere Island), refer to the White-faced Muskox (O. m. wardi), nearly all completely cover those of the other putative subspecies. [4]

Exceptions are only horn breadth at the base and mastoid breadth as a percentage of the basal length. In photographs, slight differences can be detected in the amount of white on the forehead and between the horns; but these, too, seem to be quite variable. [4]

Historically, muskoxen were categorised into seven subspecies, which later were reduced to three [2]. Today some authors still recognize two subspecies because of physical characteristics and geographical separation [1, 2, 7]:

The White-faced Muskox (Ovibos moschatus wardi) is smaller, has smaller horns. Face, saddle and lower legs are supposed to be lighter [1]. They occur naturally in North Greenland.

The Barren Ground Muskox (Ovibos moschatus moschatus) is bigger and has its distribution range on the Arctic mainland in Canada. The face is darkish. Boone and Crockett Club records clearly show that Barren-Ground Musk Oxen from the Canadian Mainland have a larger horn mass than the White-faced Musk Oxen from the Canadian Arctic Islands and Greenland. The horn bosses of mature bulls are usually wider. [2] Matschei (2012) describes them to form a „horn shield“, which is supposed to be lighter and more roundish. [7]

Distribution

by country/state: USA/Alaska; Canada; Denmark/Greenland; Norway, Russia [16]

Musk Oxen have a circumpolar distribution range. [2] At the northern coast of Greenland and on the Ellesmere Island, Canada, they inhabit some of the northernmost land on the globe. (The Inuktitut name of Ellesmere Island is Umingmak Nuna – meaning: land of the Musk Oxen.)

Historically (1800s), Muskoxen occurred from Point Barrow, Alaska (USA) east across Canada to northeast Greenland, south to northeast Manitoba (Canada), with the current range reduced (Grubb 2005). In the Canadian Arctic, Muskoxen inhabit most large islands (except Baffin Island) and the mainland tundra of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut from the coast of Hudson Bay west to almost the Mackenzie River and south to the tree line in the Northwest Territories and western Nunavut. Muskoxen occur naturally over the entire Northeast and North Greenland west to Nyeboe Land. [6]

There are several introduced / re-introduced populations [6]

- Greenland

- West Greenland (four locations)

- Qaannaaq, Northwest Greenland

- Alaska, USA

- Norway

- Dovrefjell National Park

- Svalbard – they have since died out

- Russia (The species occurred in Russia until around 2.000 years ago.) Between 1974 and 1976, 50 Muskoxen of different origin (O. m. moschatus and O. m. wardi from Banks and Nunivak Islands) were introduced to: [2]

- Taimyr Peninsula

- Wrangel Island [6]

Delineating distribution ranges of the putative subspecies, Barren-ground Musk Ox and White-faced Musk Ox, remains complex because of the vast and remote areas in the Canadian Arctic Mainland and the Arctic Archipelago and because of the reintroductions. [2]

Description

general appearance: Although not belonging to the Bovinae subfamily, Musk Oxen are bison-like. [2] Blocky body, broad head, short and stout legs, short neck, humped shoulder, and voluminous, long shaggy hair distinguish the Muskox from other Caprinae species. [16]

Adaptions to extreme cold conditions are the exceptionally thick coat and large stores of body fat that provide energy and insulation. [16] During winter muskoxen appear especially bulky. [7] Adult males are 25 per cent larger than females. [16]

White-faced Muskox – 4 years, 7 month old. It is typical for Muskoxen to hold their heads low. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

The pelage is very full, with long, coarse overhair, nearly reaching the ground [4], in some individuals actually reaching it [16]. Hair at neck, chest and hind part of the body can reach up to 90 centimetres, thus the hair of muskoxen ranks among the longest for all mammals. Hair length changes with the seasons. During winter it is longer. Females have comparably less prolonged hair. Summer coat, only in place for one month from the end of June until the end of July, gives the animals a slimmer look. [7]

Undercoat is 5 to 6 centimetres long [7], thick and wooly. [4] Inuit call it „Qiviut“. [2, 7] It matches cashmere wool or the chest hair of Vicunjas (Lama vicugna). Annually 3 to 3,5 kilograms per animal can be collected (Dathe and Schöps 1986). [7]

Change of coat is associated with temperature and photoperiodism. It starts in April and lasts until the second half of June. But long-lasting cold temperatures can retard hair change. Accordingly prevailing high temperatures trigger an early molt. It extends from anterior to posterior. [7] Young individuals are usually the first to molt. Pregnant females interrupt molting some days or weeks prior to calving. Hence farrow and pregnant females are distinguishable. [7]

head-body: 190-230 cm [7, 16]; males 220-245 cm, females 180-200 cm [7]

shoulder height: 120-151 cm [7, 16]; males 135-145 cm, females 110-125 cm [7]

Guard hairs on the back of the neck can be 30 cm long and stand upright, accentuating the neck. [2]. Musk Oxen cow and calf near Nome, Alaska. Photo: Gregory Smith

weights of captive animals: 650-700 kg [7]; 511 and 653 kg [10]; a male: 636 kg [2]

weight of newborns (captive): 7,5-12,3 kg; young of primiparae mothers are supposed to be lighter [7]

hooves: roundish; width is greater than length. Length of front hoof in males is ca. 12 cm; length of hind hoof is 10 cm. Between the toes is a broad separation line. Dew claws are rather long, but are hidden between the hairs and they usually do not leave an imprint on the ground. [7]

White-faced Muskox female – 4 years, 9 month old. Hooves are roundish. Width is greater than length. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

head: the Muskox has the tendency to stand with the head held low. [16]

scull: Orbits are strongly tubular. Rhinarium is narrow. [4]

ears: 15 cm long and pointed; hidden in the winter coat; better visible in the summer. Hearing is good. [7]

tail: usually hidden between the pelage and not visible [7]; length: 9-10 cm [16]; 10-17 cm, gland-less on the underside; the relatively short tail can be seen as an adaption to the cold – Allen’s rule [7]

Musk Oxen feces. The tail is usually hidden between the pelage and not visible. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

glands: preorbital glands are well-marked, they are more pronounced in males; both sexes have interdigital glands [7]

longevity: Muskoxen most probably do not live beyond 20 years of age [16], 24, 18-23 years [7]; examples of captive animals: 23, 24, 27 years [7]

Colouration / pelage

White-faced Muskox male – 3 years, 11 month old. General body colour is dark brown. [16] In late winter, conditioned by bleaching, the pelage may appear reddish. [7]. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

whitish parts: legs and middle back [16]; a lighter saddle patch between withers and croup is very distinctive. It is whitish or yellowish and varies individually in size. It appears in winter and summer coat. The relevance of the saddle patch is not clear. It is suspected that it accentuates the size of rutting males and especially their shoulder areas. [7]

Horns

Compared to its body the Muskox has relatively small horns. [10] Their base is very broad, covering most of the postorbital region. The horns abruptly curve down in both sexes [4] – below the eye – [16], curving up again toward the tip [4], which is very sharp [16]. Horns grow laterally in young animals. [2] Horns are very rough, fibrous basally and smooth at the tips. [4] Both sexes wear horns, but horns of males are built more strongly. [7] Mature animals have longitudinally striated horns. [2] As in sheep and goats old Muskox bulls often have broken horn tips – caused by fighting. [10] The hooked, sharp-pointed horns are an effective predator defense. [2]

horn development [7]

- 4th to 5th week: horns already start to grow [7]

- end of the second month: horn buds are 12 to 15 mm long [7]

- after half a year: horn length 7-8 cm; initially horn tips point horizontally; after half a year they show a bending [7]

- 1,5 year old male: horn length 18 cm [7]

- at 2 years: horns begin to curve forward and down [2]

- after the 3rd year: Horn tips lie in the same plane with the forehead. [7]

- with the 6th year: the horns have developed the typical Muskox-like shape [7]

White-faced Muskox – 4 years, 7 month old. Musk Oxen male with typical longitudinally striated horns. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

Young Barren Ground Muskox – 1 year, 7 month old – with typical horizontally pointed horn tips. Photo: Ralf Bürglin / Hellabrunn

horn length (of a 13-14-year-old male from Northeast-Greenland): 66,8 and 60,9 cm [7]; the median horn length of 41 registered Boone-and-Crockett-trophies is 73,3 cm; longest horn: 80,6 cm [2]

tip-to-tip spread: 64,8 to 81,9 cm [2]

horn length of a 10-year-old female: 36,8 and 37,1 cm

tip-to-tip spread (of the same female): 37 cm [7];

Female White-faced Muskox – 4 years, 9 month old. Horns of females are built less strongly. Nevertheless the hooked, sharp-pointed horns are an effective predator defense. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

diameter of horns: roundish [7]

shield: In full-grown males the thickened horn bases often meet to build a typical shield. [7] During the mating season, when males compete in a series of head-on clashes, this horn boss effectively protects the head. [2] They are rarely 15 mm apart, whereas in females horn bases are typically 14 to 20 mm apart, with hair often growing in the gap [7], especially in young cows. Median boss width: 27 cm; widest boss: 30,5 cm [2]

horn colour: whitish [4], amber-coloured [16], pale yellow [2]

Habitat

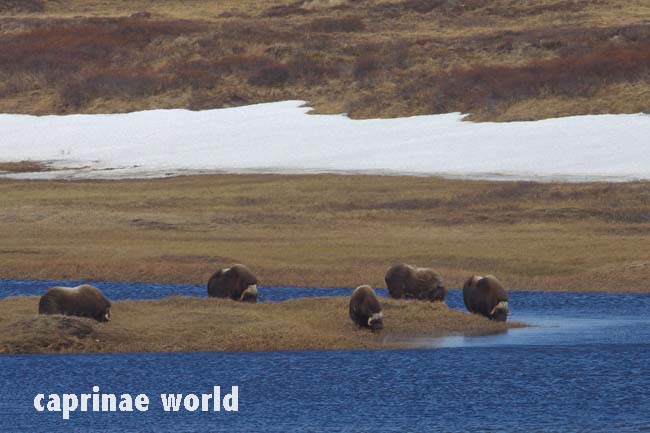

Most populations occur on tundra in areas of shallow snow or in wind-swept foraging sites with lower snow accumulation, in subarctic maritime, continental arctic, and High Arctic habitats. [16] To a lesser extend than the Chiru, the Muskox like the Argali prefers level to undulating, open terrain. [10]

In general the Muskoxen’s environment is characterised by a short and variable plant growing season (when diet quality is high) and a long winter when the availability of low quality forage is highly variable through the snow cover. Winter ranges typically have shallow snow to reduce the energetic costs of digging through snow to reach forage. [6]

Their habitats include seashore sand dunes, riparian areas, and coastal plains. On Banks Island, Canada, situated in the High Arctic, the four major habitats are characterised as wet sedge meadow, upland barren, hummock tundra, and stony barren. [16]

Muskoxen are physiologically and anatomically adapted to long, harsh, cold winters at temperatures that can be as low as -80° C with wind chill. [16]

On the Taymyr Peninsula, they experience temperatures ranging from -52°C to 25°C. On Banks Island, mean minimum daily temperatures from December to March range from -30°C to -40°C; mean maximum daily temperatures from June through August range from 5°C to 10°C. [16]

Muskoxen habitat typically receives low precipitation. [7] For example mean annual precipitation on Banks Island is 90 mm. Although Muskoxen can scrape for forage at snow depths of 20 to 40 cm, depending on snow hardness and density [16], they seem to avoid deep snow. [7]

Competitive exclusion has been proposed as a causal relationship where Muskoxen have increased and Reindeer / Caribou have declined, but conclusive ecological evidence is lacking. [16]

Food and feeding

Although primarily grazers adapted to a diet of sedges and grasses, muskoxen also browse shrubs (willows [16]) and forage selectively for forbs. [6] The species has a slow metabolism and low forage requirements, it is able to digest low-quality forage, and has the ability to accumulate large fat reserves. [16]

Forage quality is crucial for Muskoxen: In a southernmost and Low Arctic area in Greenland, where winter forage availability was higher and vegetation growth more vigorous, the animals grew faster, matured earlier, reproduced earlier, reached larger adult sizes, and had a higher rate of reproduction than Muskoxen in more northern, high Arctic areas where climatic conditions were less favourable. Few Muskox populations occur along the tree line ecotone or below the tree line. [16]

The diet of Muskoxen varies regionally depending on season and plant species availability and nutritional quality. [16]

During summer sedges (Carex sp.) play an essential role. Willow (Salix alaxensis) and alder (Alnus crispa) are gladly taken. During spring Cotton Grass (Eriophorum sp.) is grazed. During winter Labrador Tea (Ledum decumbens), Crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), Dwarf Birch (Betula glandulosa), Blueberries (Vaccinium sp.). Along coasts and in dunes they like Sand Ryegrass (Leymus arenarius) and Sea Pea (Lathyrus maritimus). [7]

On Banks Island, the Muskox diet is dominated by sedge and willow. Willow is an important dietary component during September, October, and January. Willow has a high nitrogen concentration and may complement and supplement the consumption of graminoids (grasses), although Muskoxen probably have a low requirement of nitrogen for growth. [16]

Annual diet in Taymyr Peninsula, Russia, is 47 to 86 per cent grasses, 10 to 52 per cent shrub leaves and twigs, 2 to 7 per cent lichens and 0,2 to 12 per cent mosses, which are poorly digestible. [16]

Predators / Mortality

- Arctic Wolves [5] and Grey Wolves (Canis lupus) [16], but predation by wolves does not show a significant effect on Muskox populations. [7]

- Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) [5]

- Brown Bears (Ursus arctos) – individual bears can become proficient predators [16]

In the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, calf-female ratios in June 2000 and 2001 declined to fewer than 5 calves:100 females greater than two years of age, compared to an average of 48 calves:100 females in 1990 to 1994 and 29 calves:100 females in 1995 to 1999. Increased Brown Bear predation was implicated as a major cause of the calf decline. [16]

Beside the Japanese Serow the Muskox is the only member of the Caprini, which is known to defend itself regularly against large predators. [10] When approached, Muskoxen face predators as a group, with young animals behind the group or within a circle of adults. [16]

Muskoxen may also be susceptible to internal parasites but their role in population dynamics is unknown. [6]

Although Muskox climb rocky slopes with speed and agility, Schaller (1977) cites Tener (1965) and P. Lent (pers. comm.) who see a propensity in Muskox for falling off cliffs. [10]

Mortality of young can be as high as 50 per cent. Greatest threat is low temperatures. [7]

Breeding

Muskoxen have a polygynous mating system. [16] Females have a high threshold of fat reserves before conceiving which reflects their conservative breeding strategies. [6]

sexual maturity: males at 5 to 8 years of age; until they are physically mature enough to challenge older males [16]; with 6 years [7]

female reproductive threshold: when body weight is ca. 160 kg [16]

first calving: as three years old [16]; not before the 4th year [7]

year of last calving: 18 [16]

mating season: August to September [16]

mating behaviour of males: Agonistic behaviour among males seems to help minimizing serious conflicts and avoids injuries. Conflicts can last up to 50 minutes and are ritualistic. [7]

Gray (1987) describes agonistic behaviour in 13 categories: butting, chaging, gland-rubbing, horning, pawing, pit-digging, head-tilt, parallel walk, head-swing, clash, head-pushing, hooking, chasing. Agonistic behaviour is often accompanied by roaring. [7]

Despite the ritualistic character of the conflicts, fights may become very serious. [7] Bulls may go over 30 metres apart before they turn to charge and clash with violent impact. [10] The speed of a charging bull can be 40 km/h. Clashing horns may occur up to 20 times in a row, over a course of 50 minutes. Lion like roars accompany the charges. [2] Opponents get injured and even killed. Wilkinson and Shank (1976) report from Banks Island, Canada, that 5 to 10 per cent of males die in rutting fights. Others (Lent 1988) do not confirm such high loss rates. [7]

Other behavioural elements of males during the rut incorporate olfactoric testing, lip-curling (flehming) – while standing still, head resting, leg blowing („Laufschlag“), ground and vegetation horning, digging of rutting pits [7], lateral displays, tongue-flick, and head-up. Young Muskox also neck-fight. [10]

Schaller (1977) observed courting muskox in the Calgary zoo: A bull approached a cow and stood almost parallel to her with his head facing her thigh. He kicked her repeatedly but displayed neither low-stretch nor twist. He then stood by her side, their bodies almost touching. Once he stepped behind the cow while audibly blowing air through his nostrils. Raising his leg as if to kick, he suddenly mounted. Muskox also twist, emitting low, husky sounds while doing so. Rutting bulls may also bellow. Courting bulls occasionally circle cows. [10]

White-faced Muskox female – 4 years, 9 month old. Muskoxen emit different sounds. Photo: Bürglin / Dählhölzli

times of strongest sexual activity: between 6 to 9 am and 4 to 6 pm. [7]

onset of estrus and mating: in captive animals often during the night [16]

smell of males: Dominating males smell especially during the rutting season. [7] Schaller (1977) described the smell as „strong, muskily sweet resembling that of gorilla.“ [10] The smell derives from urine that is constantly oozed; it is absorbed by the underwool. Hereby males mark themselves. According to Petersen (1958) the smell is so strong during the rutting season that the meat becomes unpalatable. [7]

gestation: 235 to 245 days [16], 244 to 252 days [7], 245 to 256 days [7]

calving: mid-April to early June [16], mid-April to June [7], which means they calve well before snow melt so lactation is supported by the cow’s fat reserves which the cow has to replenish during the brief summer. [6] Calving takes place within the herd and young are born at temperatures as low as -30° C. [16] Calving takes place every year or every second. Calf-free years occur after long winters with strong icing and deep snow. [7]

young per birth: one [7], twinning is rare [7, 16]

calves weight at birth: 10 kg [16]

calf-female-ratios (average): as high as 48 calves:100 females (greater than two years of age) [16]

behaviour associated with nursing: Both, mother and offspring may vocalise. [10]

Activity pattern

Muskoxen alternate resting and feeding. [16] The change between activity and inactivity can happen every 2,5 hours. Studies with captive animals show that the behaviour within herds is synchronised. Usually there are three maxima of activity. The one at midday is the most pronounced. Activity in the evening is less distinct compared to midday, but stronger than at night. [7]

Shifts due to age, temperature and hierarchy do occur. For example during summer active periods can be twice as high. Females and young are most active during the morning. [7] Calves tend to spend more time lying and standing and less time feeding than other age classes. Males in bachelor herds spend a greater proportion of time foraging and less time resting than they do when in mixed herds. [16]

Muskoxen spend much time with grooming, especially during molt. Animals in captivity use stones, branches or trunks to rub themselves. They also nibble their hooves or scratch themselves with their horns. While Matschei (2012) states that mutual grooming has not been documented [7], Schaller (1977) describes rubbing of rumps. [10]

Muskoxen of all age classes take baths, especially on hot days, sometimes several times a day. While young do not dare to go deep into the water, adults can be seen swimming. Being in the water also stimulates the play instinct. During the warm days of summer Muskoxen seek snowfields to cool themselves. [7] Musk Oxen near Nome, Alaska. Photo: Gregory Smith

Threatening behaviour

When Muskoxen threaten they exhibit a mode of behaviour that is unique amongst bovid species: They rub their preorbital glands on the inner sides of their front limbs (Gray 1987). Gland rubbing occurs during agonistic encounters between individuals, groups or predators. Young display this behaviour playfully already after their first week. Females and subadults rub less often and predominantly when confronted by predators such as wolves. [7]

Barren Ground Muskox calf, 4 month old. Like all Caprini species young Muskox are followers. [10] Photo: Ralf Bürglin / Tierpark Berlin

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

Most populations have regular patterns of local movements and seasonal migrations. [16] Muskoxen move an average of 2 kilometres daily between feeding sites. Muskoxen migrate from sheltered, moist lowlands in the summer to higher, barren plateaus in winter. The primary reason for this is food – the exposed plateaus do not accumulate snow due to the prevailing high winds, therefore making forage easier to find and reducing the energy cost of digging for forage. Muskoxen generally travel not further than 80 kilometres between summer and winter areas. They also cross sea-ice between islands of the Arctic Archipelago (Lent 1988). [2] Some tagged animals have been recorded to move 120 to 130 kilometres. However long distance migrations, as performed by Caribous (Rangifer tarandus), do not occur in Muskoxen. [7

Herd size varies with the season. Herds are bigger during winter. [7]

herd size in summer: 5-12 animals [16]; 10-15 [7]

herd size in winter: 2 to 30 animals [16]; 15-20 [7]

Former Arctic voyagers reported herd sizes exceeding 100 individuals. Winter herds can consist of combined single herds. Tener (1965) cites R. Smith, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who sighted 10 single herds and 4 solitary males combined in one herd counting 164 heads on Bathurst Island, Canada, in 1950. [7]

Behaviour within herds: Members of a herd typically stay closely together, single animals rarely exceed 50 to 60 metres distance from each other. Minimum individual distances between herd members are just around 3 metres. When animals rest, the individual distance can be shortened to just 1 metre, but direct contact between adults and adolescents is avoided. [7] Groups may exhibit loose cohesion; shifting of individuals between groups is characteristic. [16] Herds seem to be more stable during the summer. [7] In the Taymyr Peninula, Russia, herd size consisted of 17 to 23 animals at high population densities. Large populations can have densities of 1,5 to 2 ind./km². [16] Nowak (1999) ascertained a density of 0,30 to 0,44 ind./km² in Greenland. [7]

Adult males occur as harem bulls in mixed herds, in bachelor groups, or alone [16]. Solitary bulls are mostly 5 to 6 years old or older. Their numbers grow towards the summer to reach a maximum at the end of July and in August. They may join herds again. Very old males, which do not participate in reproduction any more, may permanently stay alone, although they are usually less aggressive. Dominant males are so busy herding females during the summer that they may face winter in bad condition. Hence death due to exhaustion is a factor. [7]

Young males tend to remain in herds with their mothers until the age of two. Some remain with female herds until they are subadults, depending on the aggressiveness of dominant males. [16]

Status

IUCN classifies the species under „least concern„. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [6]

Muskoxen were historically present from Point Barrow in Alaska, and extended across the circumpolar Arctic through Canada into North-eastern Greenland, and south as far as North-east Manitoba. In the 19th century the species became extinct in Alaska, but was reestablished from Greenland stock, initially on Nunivak Island, in 1936. Nunivak Island Muskoxen were introduced on Nelson Island and into North-eastern and North-western Alaska and the Seward Peninsula between 1967 and 1981. The introduced populations in North-eastern and North-western Alaska are the only ones living within the historical distribution of the species. [16]

From North-eastern Alaska, Muskoxen spread to North-western Yukon, in Canada. They were never extirpated in Canada or Greenland, although their distribution became reduced in the former. Now Muskoxen naturally occur on the tundra west of Hudson Bay in Nunavat, Canada, and extend westward through the Northwest Territories, reaching almost to the Mackenzie River. They are also present on most of the larger islands of the Arctic Archipelago, with the exception of Baffin Island, and have been introduced into Northern Quebec. [16]

Extinct in Russia for 2000-3000 years, they were successfully reintroduced on the Taymyr Peninsula and also on Wrangel Island and Yakutia (Anabar River, Ust-Lensky Narture Reserve, and Indigirika River) in Siberia. [16]

Today (2008) the number of mature individuals is estimated to be between 133.914 and 136.914. [6]

In Canada, estimated muskox numbers in the Northwest Territories total 75.400 (1991-2005) of which 93 per cent occur on the large arctic islands of Banks and western Victoria. Nunavut has an estimated 45.300 animals, of which 35.000 occur on the Arctic islands (unpublished data). A few muskoxen from the transplanted population on the Alaskan North Slope have strayed into Yukon. In northern Quebec (outside their natural range), Le Henaff and Crete (1989) counted 290 muskoxen in 1986. [6]

In Alaska, 3.714 animals were estimated from aerial and ground counts between 2001 and 2005: Nunivak Island 609; Nelson Island 318; Seward Peninsula 2050; northwest Alaska 369; northeast Alaska 268. The re-established herds either fluctuate or are increasing in size and range, and in some areas, local people are concerned that they will compete with caribou and reindeer. [6]

The population size in Greenland in 1991 was estimated to number 9.500-12.500. Of this total, Boertmann et al. (1992) recorded the following population estimates: 1.000 to 1.500 in North Greenland between Newman Bight (82°N, 55’W) and Nioghalvfjerdfjorden (79°N); around 35 animals in the northern East Greenland region between 79°N and Jokelbugten (78°N); 450 to 550 between 78°N and Ardencable fjord (75°N); 2.900 to 4.600 in the areas between 75°N and Kong Oscar Fjord (72°N), and 4.600 to 5.000 the southernmost part of the species’ natural range in East Greenland, between 72°N and Scoresby Sund (70°N) (although recent unpublished surveys suggest that the population here has been reduced to approximately 4.000 animals (P. Aastrup pers. comm. to M. Forchhammer). [6]

In Russia the number of muskoxen has been evaluated to be 2.000 individuals. [16]

Threats

Historically this species declined because of over-hunting, but population recovery has taken place following enforcement of hunting regulations. Management in the late 1900s was mostly conservative hunting quotas to foster recovery and recolonisation from the historic declines. [6] Some populations have increased dramatically, particularly those on Banks and Victoria Islands, where almost two thirds of Canadian Muskoxen now occur. (Gunn 1990; Gunn et al. 1991) [2]

Currently, there is increasing realisation that periodically on some arctic islands, die-offs of up to 40 per cent of the island’s muskoxen occur when warmer fall weather leads to icing and deeper snow which restrict forage availability. The environmental consequences of climate warming is likely to have an impact on this species. [6]

On the North American mainland, typically muskoxen have expanded their range recolonizing historic ranges but behind the colonizing edge, abundance declines at least partially due to predation by wolves and grizzly bears. A persistent concern of people is that muskoxen through their presence (smell) and foraging are detrimental to caribou (Rangifer tarandus). [6]

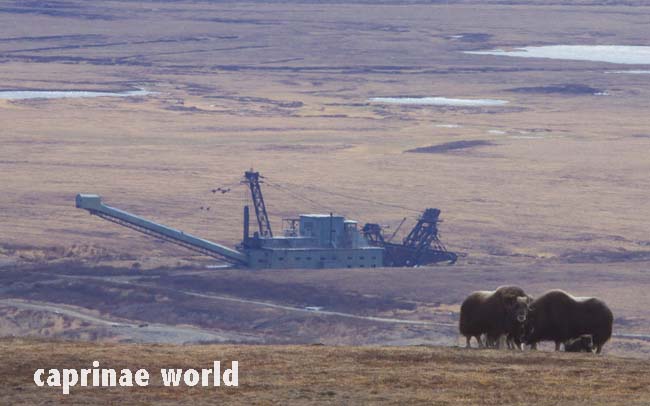

Land utilization is not reported to have an effect on Muskoxen. Location: near Nome, Alaska; photo: Gregory Smith

In Greenland, there are no major threats, although the fact that populations are often small in size and scattered, make them vulnerable to local or regional fluctuations in climate. Most populations are within the National Park, where they are protected from hunting. The portion of the population which is south of the National Park sustains a regulated quota harvest. Climate change in Northeast Greenland is expected to bring increased precipitation and milder winters, which might negatively affect the muskox population. [6]

Conservation

In the past unregulated commercial harvesting caused the disappearance of muskoxen from large areas of their Canadian continental ranges in the late 1880s and at the same time, ice storms probably reduced muskox numbers on Banks and western Victoria islands. After protection from hunting in 1917, muskoxen began to recover, and under the Northwest Territories and Nunavut Wildlife Act, are subject to aboriginal hunting limited by area-specific quotas and seasons. After 1980, the rights to hunt muskox could be transferred to non-aboriginal hunters for guided non-resident hunters and for commercial meat harvesting. [6]

In Northern Canada, wildlife management is largely shifting from centralized government agencies to co-management boards and shared responsibility with aboriginal peoples. The wildlife management boards are developing management plans, and continue to regulate muskox hunting on the basis of sustainable yields. In the late 1990s, the annual quota for the NWT and Nunavut was 12.000 animals which includes 10.000 tags for Banks Island. The domestic harvest is relatively stable and while the commercial harvest for meat and hides (source of qiviut, the fine underwool) annually varies, it averages about 1.000 to 2.000 muskoxen from Banks and Victoria islands. [6]

Management activities in Canada are mostly systematic aerial strip-transect surveys to track trends in population size, and as a basis for quota adjustments. No reserves are specifically set aside for muskoxen, but part of the rationale for establishing the Thelon Game Sanctuary was to protect a remnant muskox population from hunting. [6]

The species occurs in three national parks in Canada [6]

- Quttinirpaaq (Ellesmere Island )

- Aulavik (northern Banks Island)

- Tuktu Nogait (Bluenose Lake, western Arctic mainland)

In national parks, land use activities are controlled, but aboriginal hunting is permitted subject to conservation provisions. [6]

Conservation measures proposed for Canada:

1) Maintain sufficiently frequent population monitoring to track trends in abundance and distribution

2) Utilize environmental screening of individual developments to protect muskox ranges outside any formally protected areas

3) Public education is essential as muskox have recolonized large areas and many people are unfamiliar with muskox ecology and behaviour. People are often concerned about effects of muskoxen on caribou especially in areas muskoxen have recolonized. [6]

In the United States, all five extant populations are the result of re-introductions of the muskox within and outside its historic range. The re-introductions began in 1935 with the translocation of animals, originally from northeast Greenland, to Nunivak Island. From 1967 to the most recent transplants in 1970, the Nunivak island population has been the source for all other Alaskan translocations (Klein 1988). Fully protected by law, muskox occurs in five protected areas and hunting is allowed under permit, with limited quotas on three of the five populations. Local subsistence hunting is given preference. Its status within the country is Not Threatened. [6]

In Greenland, muskoxen occur in four protected areas, where they receive full protection [6]:

- Northeast Greenland National Park (indigenous population) – vast area

- Arnangarnup Qoorua Nature Reserve (introduced)

- Kangerlussuag Reserve (introduced)

- Maniitsoq Caribou Reserve (introduced)

Most natural populations are within Northeast Greenland National Park. Outside protected areas, controlled hunting is allowed on Jameson Land in East Greenland, and near Kangerlussuaq in West Greenland. In both, quotas are determined annually and hunting is permitted only by full-time subsistence hunters. Between 1963 and 1991, muskoxen were translocated to three areas in the southwest previously uninhabited by muskox (near Kangerlussuaq, central West Greenland; Nunavik Peninsula, West Greenland; and Ivittuut, south Greenland), and a fourth population was reintroduced into former muskox range in Avanersuaq (Thule) in north-western North Greenland. [6]

Conservation measures proposed for Greenland: A proposal for development of a long-term management plan for existing muskox populations in West Greenland, is presently being considered by the Home Rule administration. A new system of game wardens in the West Greenland region, between Disko Bay (68°30’N) and Paamiut icecap (62°30’N), is being established to strengthen the enforcement of renewable resource legislation, and to control the performance of hunters in general. [6]

Hunting

The hunting of this species is now well regulated and is believed to be sustainable. [6]

Trophy hunting for Muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic opened in 1986 and must be conducted with Inuk outfitters and guides. Hunters usually travel with snowmobiles. [2]

Information for Greenland is contradicting: While Gunn and Forchhammer (2008) state that hunting is permitted only by full-time subsistence hunters, Damm and Franco (2014) write that on Jameson Land in East Greenland, and near Kangerlussuaq in West Greenland some limited trophy hunting takes place. [2, 6]

In Alaska, Muskox hunting is allowed under permit, with local subsistence hunting given preference, and limited quotas on three of the five populations. [2]

In Russia hunting Muskoxen is prohibited, but the harvesting of post-prime bulls is contemplated. [2]

Ecotourism

Mammal watchers report Muskoxen from Nome, Alaska, and the Dalton Highway. Probably one of the most popular Muskox watching destination is Dovrefjell in Norway, where Muskox safaris take place.

Literature cited

[1] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[5] Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.), 1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie, Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

[6] Gunn, A. & Forchhammer, M. 2008. Ovibos moschatus (errata version published in 2016). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T29684A86066477. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T29684A9526203.en. Downloaded on 06 February 2019.

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[10] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain Monarchs – wild sheep and goats of the Himalaya. The University of Chicago Press

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.