The Aoudad is a goat-like caprid from northern Africa. It is a very robust and highly reproductive species.

Names

Algeria: arrouy [2]

Egypt: kebsh el gebel, wadden [2]

English: Aoudad, Barbary Sheep, Uaddan [6], Arrui [16]

French: Mouflon à Manchettes [6], Aoudad de Barbarie [16]

German: Aoudad, Mähnenspringer, Berberschaf, Mähnenschaf, [6]

Libya: arui, waddan [2]

Morroco: drrui [2]

Russian: Гривистый баран [Wikipedia, 2]

Spanish: Aoudad [2], arruí, arrui, carnero de berbería [Wikipedia]

Tunisia: naded, naddan, oudad [2]

The binomial name derives from the Greek ammos (sand) and tragos (goat). Lervia derives from the wild sheep of northern Africa described as „lerwee“ by Rev. T. Shaw in his „Travels and Observations“ about parts of Barbary and Levant. The vernacular name aoudad has its origins in the Berber language. [2]

Taxonomy

Antilope lervia Pallas, 1777, North Africa [16]

diploid chromosome number: 58 [2, 16]

The Aoudad has been hypothesized to be an ancestral form of sheep (Ovis) or goat (Capra). The Aoudad has the same diploid chromosome number (58) like the Ladakh Urial (Ovis vignei) – a wild sheep -, but it interbreeds with goats not with sheep. Molecular data also reveal a closer relationship to goats. [16] In fact Aoudad are goat-like in many characteristics except for the lack of a chin beard and the shape of the horns. Rams even have a goat-like smell during the rut. [2]

Taxonomic affinities deduced from Aoudad behaviour: Aoudad males favour such primitive forms of combat as neck-fighting and the head-to-tail. Goat-like, they insert their penises into their mouths but do not urinate on themselves. They do not use the jump as a form of threat, as do sheep and goats. Two combatants may clash by running sheep-like at each other on all fours. Aoudads are not as specialized as true goats, prominently displaying some primitive fighting styles, foregoing urine marking, and clashing without first rearing up. On the basis of the behavioural evidence I (George Schaller) surmise that Aoudad split from the goat stock shortly after the sheep and goats diverged onto their separate evolutionary paths but before the ancestors of Tahr (Hemitragus) and goat (Capra) acquired their specialized urine spraying and distinct method of clashing. [10]

Subspecies

The restriction to mountain ranges in the Sahara and the Maghreb suggests that there should be strong geographic differentiation. [4] But the isolated populations of the Aoudad show only slight morphological differences, and have been described as four (lervia, fassini, ornata and blainei) – see Allen 1939, Harper 1945, Haltenorth and Trense 1956, Trense 1989) – to six subspecies (Gray 1985 – adding saharensis and angusi). [2]

In 2000 at the taxonomy workshop of the IUCN Caprinae Specialist Group, delegates felt that the subspecies angusi, blainei and fassini may not justify subspecific status and should possibly all be reclassified as fassini, while the saharensis subspecies was considered as being valid. [2]

Atlas Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia lervia) Pallas, 1777 [16]

Egyptian Aoudad (A. l. ornatus [ornata]) I. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1827 [6, 16]

Libyan Aoudad (A. l. fassini) Lepri, 1930 [16]

Kordofan Aoudad (A. l. blainei) Rothschild, 1913 [16]

Aïr Aoudad (A. l. angusi) Rothschild, 1921 [16]

Saharan Aoudad (A. l. sahariensis) Rothschild, 1913 [16]

Old male (A. l. angusi) in the dark rocks of the Termit massif (Sahara, Niger). Photo: Alain-Dragesco-Joffé

The Saharan Aoudad has a sandy rufous pelage. It is paler than all other subspecies. Photo: Bürglin / Jerez de la Frontera

Apart from certain distinguishing characteristics in pelage and horn morphology, there are still many open questions regarding the exact distribution areas and potential intergrading zones of different types. It would probably be useful to at least describe the core populations in these different areas as „Distinct Population Segments“ (DPS); they certainly merit special conservation and management efforts and a DPS status will enhance efforts. [2]

Similar species

Stripped of its distinctive ruff, the Aoudad resembles the Dagestan Tur (Capra cylindricornis). [10] The horn shape of mature Aoudad rams shows again some similarity to the horns of the Daghestan Tur, but also to the Bharal (Pseudois sp.). [2] Concerning the hair accessories Aoudad resemble the Arabian Tahr (Hemitragus jayakari).

Distribution

by country: Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Sudan, Tunisia; its presence in Western Sahara is uncertain [6]; introduced free range in: Spain, Mexico, USA (Texas, New Mexico, California, Colorado) [2]; Croatia

Detailed range description (although the present distribution over much of their range is still unknown [16])

The Aoudad was formerly widespread in rugged and mountainous terrain from deserts and semi-deserts to open forests in North Africa. But it has suffered a strong decline due to poaching and competition from domestic stock. The ranges of the six supposed subspecies can be summarized as follows [6]:

Atlas Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia lervia) occurs in the mountains of Morocco, except the western half of the Rif, and in northern Algeria and northern Tunisia. [6] They are present in the following protected areas in Morocco: Eastern High Atlas national park, Toubkal national park, and adjacent Takherkhort Hunting Reserve. Animals from this reserve have been used for re-introductions to other, mostly smaller areas and hunting reserves, which Aoudads occupy only seasonally.

The Atlas Aoudad shows the greatest altitudinal distribution range for the species. In the Atlas Mountains it occurs in steep and rocky habitat up to 3.960 metres. However, it is also present on the slopes of lower desert mountains in the Sahara (Gray 1985). The boundary between the Atlas and the Saharan Aoudad in Southern Morocco, Western Sahara and south-eastern Algeria is unclear. [2]

Egyptian Aoudad (A. l. ornata) was formerly quite widespread throughout the Eastern and Western Desert of Egypt. It was thought extinct (see Amer 1997). However, Wacher et al. (2002) reported evidence of the presence of Aoudad in both the Elba Protected Area and the Western Desert between 1997 and 2000 (Manlius et al. 2003). [6]

Kordofan Aoudad (A. l. blainei) were once relatively widespread from west Sudan to the Red Sea coast, but currently are restricted to areas that are far apart from each other, namely the Red Sea Hills of Northeast Sudan (Nimir 1997) and the Ennedi and Uweinat Mountains in Northeast Chad, Sudan and the most south-easterly tip of Libya. [6, 2]

Libyan Aoudad (A. l. fassini) is found only in extreme southern Tunisia (Bou Hedma Reserve [2]) and in Libya [6] in three separated subpopulations in eastern, central and western Libya (Murzuq and Socna, Hamada el Homra, south of Gatroum and Kufra). [2]

Aïr Aoudad (A. l. angusi) inhabit the Aïr Massif (Niger) and Termit Massif (Niger). [6] Misleadingly the Adrar de Iforas, in the border region between Mali and Algeria and the east in the Tibesti Mountains of Chad are included in the distribution range of this subspecies. [2]

Saharan Aoudad (A. l. sahariensis) has the largest range of the subspecies, including southern Morocco and Western Sahara, southern Algeria, South-west Libya, Sudan, the mountains of the Adrar de Iforas in Mali, Niger, Mauritania, and the Tibesti Massif. There were no reliable reports of the species in the Western Sahara since the surveys of Valverde (1957), but the possibility of it’s survival in the Oued El Dahab was noted by Aulagnier and Thévenot (1997), and the species was recently rediscovered in this country (Cuzin 2003; Cuzin et al. in press). [6] The northern boundaries with Atlas Aoudad and the southern boundary with the Aïr Aoudad are unclear. [2]

Aoudad have become a widespread invasive species [16] and have been introduced into the United States (California, New Mexico, and Texas), northern Mexico, Spain (mainland and the Canary Islands (La Palma)) (Gray and Simpson 1980; Grubb 2005) [6, 16]. There is also a population in the Mosor Mountains, Croatia (visited by the author – see report).

Subspecies of free-ranging introduced populations are unknown because they originate from zoo animals of uncertain origin or from hybrids. Most introduced animals are probably from the subspecies lervia. [16]

Origin: Eurasia or Africa?

Schaller (1977) pointed out that it is not clear whether Aoudad emigrated from Eurasia to its present geographical range in northern Africa, or whether it evolved in Africa from one of the primitive Caprinae that occupied the continent during the Miocene and later. Aoudad fossils date to the Pleistocene (iceage) when A. palaeotragus was found in North Africa. Ancestors of the Aoudad may also have occurred in Europe where several forms (Ammotragus magna or Ovis magna and Ovis primoeva) are possibly related to the African animal (Ogilby 1965 in Schaller 1977). Rock paintings in Algeria, and Egyptian tomb and temple reliefs, suggest that Aoudad was an animal of considerable economic and cultural significance (Gray 1985). [2]

Description

general appearance

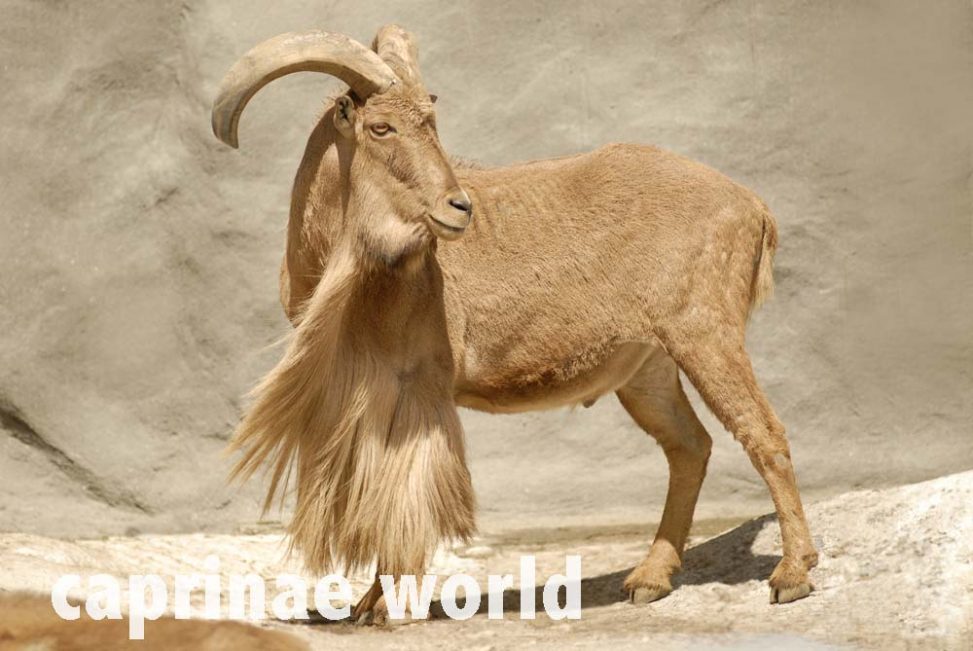

General description – George Schaller put it his way: „The Aoudad with its pale tawny body … would be nondescript were it not for its distinct beard that begins near the throat and extends to the chest, and for its floppy hairy leggings.“ [10] Photo: Bürglin / Hagenbeck, Hamburg

head: relatively long [2]

ears: narrow and evenly tapered [2]

the hair in more detail: Adult males have prominent long hairs on the cheeks, the throat, and the front of the neck, extending to the brisket. Another feature is the long hair on the anterior of the upper part of the front legs. The hairs on the brisket and legs can extend to the ground. [16] Females also have these hairy appendages though in abbreviated form. [10]

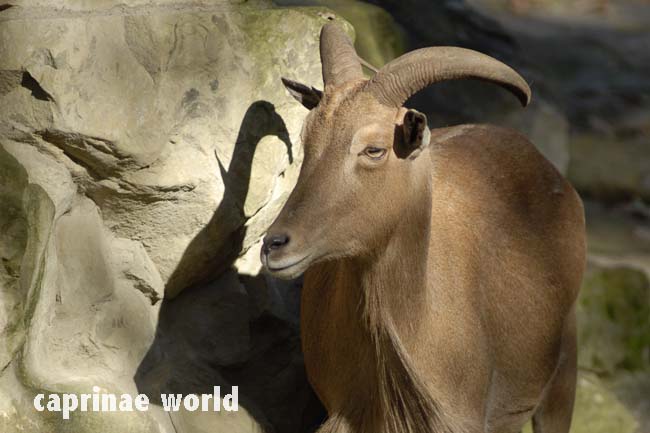

In both sexes a short, erect hair line extends from the base of the neck to just behind the withers. [16] Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

Aoudad have long hair on cheeks, throat, front of the neck, extending to the brisket and on the upper part of the front legs. Photo: Bürglin / Hagenbeck, Hamburg

callus on „knees“: Like goats most adult Aoudad have this bald area of thickened skin on their „knees“ – better carpal joints – of the front legs [10]

hooves: blunt [2]

tail: 17,5 to 20,5 cm long [16]; 15-20 cm [2];

glands: only subcaudal glands; pedal, preorbital, and inguinal glands are not present [2, 10]Following measurements and weights mentioned under [16] are from captive specimens. Wild animals probably are smaller. [16]

body length (means): 128 cm males; 112 cm females [16]; 155 cm and 165 cm males; 130-140 cm females [2]

shoulder height: males 92-110 cm; 80-85 cm females [16]; males 90-112 cm; 75-94 cm females [2]

weight (means): males 82 kg (up to 145 kg); females 41,3 kg (up to 86 kg) [16]; males 100-145 kg; females 30-64 kg [2]

Colouration / pelage

The outer coat has a general rufous, reddish, chestnut or sandy to tawny brown colouration with occasional dark areas or marks about the head and the forequarters. [2]

whitish parts: chin, undersides, and inside of legs [16]; a circular spot of white hair can be present on the head between the horns. [2]

This specimen exposes its throat, which is also whitish. Aoudads don’t have a chin beard. Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

rump patch: no [10]

scrotum: conspicuously large and pale [10]

Horns

The horn shape of mature Aoudad rams is not overly reminiscent of wild goats in general, but has some similarity to the horns of the Daghestan Tur (Capra cylindricornis) and the Bharal (Pseudois sp.). In general, Aoudad horns are more sheep-like, similar to those seen in some moufloniforms. This may be why Aoudads are also called „Barbary Sheep“, although this expression is technically incorrect. [2] In general they are heavy, corrugated horns sweeping out, back and in. [10] They are keeled in cross-section, with a fairly broad frontal surface, showing numerous uniform, shallow, transverse rings or wrinkles. In older animals these wrinkles may be worn down, making the horn surface look smooth. [2] Both, males and females possess horns [16]

The horn surface shows numerous rings or wrinkles, but is prone to abrasion. Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

horn colour: yellowish-brown, darkening with age (Lydekker 1913) [2]

longest recorded male horn length (one specimen from Africa): 87,9 cm [2, 16]

basal circumference: 33,2 cm [16]; up to 35 cm [2]

tip-to-tip spread: 39,4 cm [2, 16]

Horns of females: Horns of females are less massive but can be equally long [16], but are generally one third smaller and shorter. [2] Aoudad and Thar are the only Caprini in which females also have large horns. [10]

Habitat

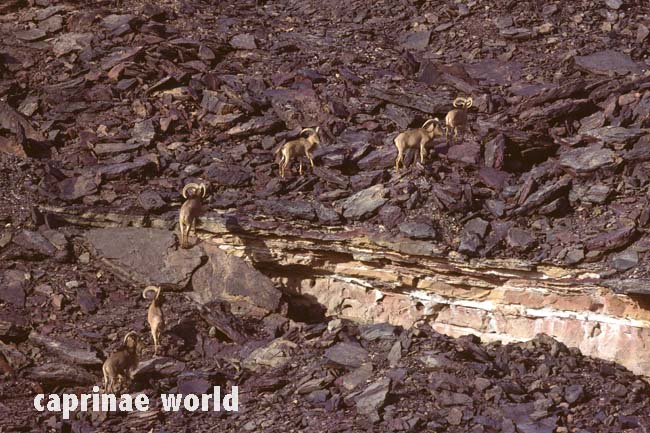

Aoudads in Africa occur from arid to semi-arid mountainous, rugged, broken terrain to open forests with a precipitous component. [16] They tend to inhabit areas, from near sea level (200 metres) up to snow-free areas at about 4.100 m (such as the Moroccan Atlas). They also require rocks or sparse tree cover for shade, and might wander far from water sources for long periods of time. They probably make small migratory movements in relation to food availability. [6]

Barbary Sheep (A. l. lervia) in the Atlas-Mountains, Morocco near Marrakech, 2018-05. Photo: Christopher R. Scharf

Adult male (A. l. angusi) early morning in the Aïr massif (Sahara, Niger) amidst huge boulders. Photo: Alain-Dragesco-Joffé

Six big males (A. l. angusi) in the Termit massif (Sahara, Niger) in a very barren landscape. Photo: Alain-Dragesco-Joffé

Introduced populations do well in a variety of habitats, including montane areas associated with canyons and gorges, level terrain with brushy vegetation, and woodlands and grasslands, but Aoudads prefer precipitous terrain. They can survive in areas without rainfall.

In California, in a Mediterranean climate, Aoudads used woodlands in summer, grasslands in autumn and winter, and rugged terrain in spring, during the lambing period.

In Spain, in an area consisting of three habitats (open with shrubs, closed formed by forests, and mixed habitats consisting of shrubs with scattered trees), neither adult females nor subadults showed preference for a particular habitat.

During the parturition period, no animals of either sex were observed in closed forest; males were most frequently sighted in mixed habitats and females in open shrub habitats.

During the mating season, in October, Aoudads were mostly observed in closed rather than open habitats.

Population parameters and habitat use can be variable due to variability in population size, habitats, and rainfall and forage production within and between years. [16]

Food and feeding

The Aoudad is a generalist herbivore combining grazing with browsing. [6, 10] Vegetation in the Aoudad’s native habitat is sparse, a few acacias, some shrubs, and a thin ground cover of grasses (Brouin, 1950), a habitat similar to that used by Wild Goat and Nubian Ibex. [10] Aoudads adjust to available forage. [16] Photo: Petra Wiedemann / Sierra Espuña

Mortality / Predators

In the introduced populations in America predators include Coyotes (Canis latrans) and Pumas (Puma concolor), but predation is usually not a significant mortality factor in the USA or Spain. Although diseases and parasites are usually insignificant causes of mortality, there have been population die-offs caused by a helminth nematode (Elaeophora schneideri) in the USA and mange (Sarcoptes scabiei) in Spain. The greatest adult mortality factor in the USA is hunting. [16]

Breeding

first mating: females at 18 months [16]

sexual maturity: males 11, 14 or 18 months respectively; females 19 months and exceptionally with 7 months; Gray and Simpson (1980) indicate that the beginning of sexual maturity is variable. [7]

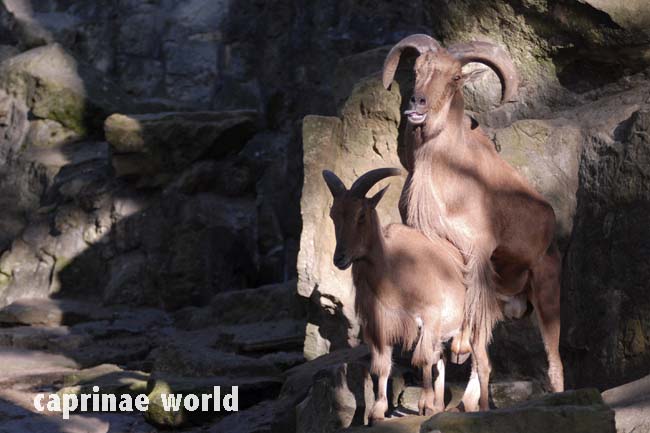

Aoudad rut throughout the year with the main mating season depending on local climatic conditions [2]; September to November [16]; in Niger Juli and August [7]; Aoudad in California mate all year, but still retain birth peaks [10] Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

lambing season: March and April; but parturition can occur in other months [16]

Females give one or two young per birth [16], also triplets have been reported [2]; but only multiparous females – females that have given births before – produce twins [16]. In a New Mexico study 58 per cent of all females were found to have twins. [10] Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

high-ranking females: have shorter interbirth intervals; produce heavier offspring; have a higher proportion of male twins; wean their offspring earlier – proved in a captive population [16]

vocalisation related to nursing: in many caprinae species female may initiate nursing by calling, in Aoudad (and Muskox) both mother and offspring may vocalize. [10]

reproduction potential: high – Aoudad introduced into Texas increased from 42 to 600 in 10 years. [10]

Activity pattern

Aoudads are mostly diurnal, but their grazing periods can be equally divided between night and day. When disturbed by humans, feeding activity will shift to night. [16]

During warm weather, Aoudads rest in shaded areas. Accordingly there is an increasing period of inactivity during the day from winter to summer. Rough, steep terrain is used significantly more for resting sites. [16] Photo: Bürglin / Al Ain Zoo

Prior to parturition, females isolate themselves in rugged terrain. They do not rejoin herds until the neonate is able to follow their mother, usually within two days. [16]

Other behavioural patterns

Aggressive behaviour: Katz (1949) and Haas (1958) studied Aoudad behaviour in captivity. George B. Schaller (1977) supplemented their observations with his own: Animals jerked, lunged and butted, but did not chase and jump. Katz (1949) described clashing: „The sheep walked rapidly toward each other, gradually picking up speed and breaking into a run shortly before they collided. Just before impact their heads were lowered and turned slightly to opposite sides. They attempted to meet squarely with their noses crossed … [10] In general it is said that intensive fights are rare. [7]

Another type of fighting consisted of close butting, and locking and twisting horns … Each tried to twist the head of the other by pulling downward and away. Also, attempts were made to hook the belly or the flank.“ One animal may also run into a clash while the other waits with lowered head, catching the blow between its horns. Clashing with a sideways jerk of the head when two animals walk parallel is common too. The shoulder-push is a conspicuous pattern, and sometimes one or both combatants hook a horn over each other’s neck or shoulders and pull as well as shove. [10]

Aoudad also push while standing head-to-tail. The head-to-tail is seen as a phylogenetically old combat method, which have been relegated to minor positions in most advanced Caprini. The head-to-tail is rare among sheep (Ovis sp.) and wild goats (Capra sp.), but it has been retained as a common pattern by the Aoudad. [10]

By placing its head and neck on the rump of the other, an Aoudad may force its opponent onto its knees (Haas, 1958). Horn pulling is often seen with the animals standing parallel or head-to-tail and sometimes pushing with the bodies too. The neck-fight is a complex and prominent pattern. At its simplest, one Aoudad places its head and neck over the body of the other and presses down, sometimes until the animal sinks to its knees. The full weight of the body may also be used, with the attacker draping his whole forequarters so far over the shoulders of the other that his head hangs down the other side. [10]

fighting females: Among captive Aoudad „fighting was almost as common among the ewes as among the rams“ except during the rut (Katz, 1949). [10]

courtship behaviour: Aoudad low-stretch and twist but do not kick. [10]

Penis sucking: An Aoudad may jerk his extended penis against his belly and insert it into his mouth (Haas, 1985), but does not urinate on himself like goats do. Aoudad have also been observed as they lay „on their backs and sucked their penises for short periods“ (Katz, 1949). – Sheep do not mouth their penises except on very rare occasions. [10] Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

Grooming: Aoudad – like Mountain Goats – take dustbaths by lying down and throwing sand over their bodies with their horn tips (Katz, 1949). [10] Photo: Bürglin / Zoo Berlin

vocalisations: Aoudads use a variety of vocalisations such as bleating (blöken, meckern), snorting (schnauben), screeching (kreischen) and guttural growling/grunting (knurren) – (Gray 1980). [2]

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

Daily movements of three Aoudads ranged from 0,2 to 3,4 km. Diurnal movement ranged from 0 to 1,9 km, without significant differences between seasons. [16]

Annual home ranges of two rams averaged 1547 ha and the home range of one female was 764 ha, indicating that males have larger home ranges than females. [16]

Released animals dispersed 32,3 km within 5 to 7 months. [16]

Abrupt seasonal movements of up to 23,4 straight-line kilometres are known. [16]

Aoudads are gregarious and develop a dominance hierarchy within herds, but individual female rank can change depending on age and reproductive history. [16]

Mixed herds composed of adult males and females, subadults, and young usually formed during rut, have 2 to 63 animals, with a mean size of 14,7. Nursery and mixed herds in a population of 500 to 600 have 2 to 45 individuals, with a mean of 7,9. In another study, mean group size declined from 25 after the rut to 5 in the summer and increased during the autumn and winter; especially during the rut, when adult males joined female herds. One population consisted of 30 per cent juveniles and subadults, 20 per cent males, and 50 per cent females. [16]

Ability to recognize close relatives: In a captive population study, the higher the relatedness and age similarity, the closer the distance between individuals, indicating an ability to recognize close relatives.

Survival rates were 35 per cent for the neonate to one-year-old cohort, 77 per cent for males 1 to 3,5 years of age, and 55 per cent for males 3,5 to 10,5 years of age. [16]

Longevity in the wild is 10 to 12 years and in captivity 24 years [16]; rams rarely survive the 10th or 11th year [2]

Status

IUCN classifies the species as „vulnerable“. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [6]

The total population size is in the order of 5.000 to 10.000 individuals [6]. The species has undergone widespread extirpations and population decreases throughout most of their former range, including Egypt, Sudan, Libya, Chad, and Western Sahara. [16] It was estimated (2008) that a decline in excess of 10 per cent will occur over the coming 15 years (three generations) mainly as a result of (uncontrolled) hunting and habitat loss. [6]

Algeria: several thousand animals

Chad, Mauritania and Mali (Adrar des Iforas): low numbers

Egypt: Once regarded as extinct, Aoudads seem to be locally numerous in the Eastern and Western Deserts of Egypt (M.A. Saleh, in Cassinello in press).

Libya, Western Sahara, Tunisia: no estimates

Morocco: The total population is estimated to be between 800 and 2.000 animals (Cuzin et al. in press)

Niger (estimates available for the Air and Tenere National Nature Reserve): within the reserve – 3.500 animals; outside the reserve – 700. Populations in the Air mountains appear to be increasing. For the country as a whole the population trend is overall downward.

Sudan: no population estimates available, but the species is generally regarded as very rare and almost certainly declining (Shackleton 1997; and references therein). [6]

Introduced populations: [16]

Texas: 12.000 [16]

New Mexico: 4.000 [16]

California: 400 [16]

Mexico: fewer than 1000 [16]

Spain: 1000 [16]; since 1970 in Sierra Espuna [7]; Canary Islands: 1972, La Palma [7]; several hundred [16]

Germany: started 1883; introduction unsuccessful [7]

Italy: before 1950; introduction unsuccessful [7]

Threats

The major threats across the range include poaching and habitat destruction, mainly from livestock grazing, fuelwood collection, and from drought and desertification. In the Western Sahara, hunting by soldiers has been a serious threat, and here the species might already be extinct (Valverde 1968). The decline of Egyptian Barbary Sheep has no doubt been accelerated by competition with livestock and feral camels. The availability and distribution of waterholes would likely be a major factor in the condition of populations, and both may fluctuate from year to year. [6]

Free-ranging, introduced Aoudad populations are a major management concern because of their potentially deleterious impact on native wildlife such as deer and especially native Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis) in the USA and Mexico and the Iberian Ibex (Capra pyrenaica) in Spain. [16] On the other hand in times of climate change and prevailing terrorism to establish populations may be justified.

These peculiarities make introduced Aoudad a management challenge [16]

- has a high birth rate

- is adaptable to a wide variety of habitats and foods

- lacks significant predation

- is resistant to native and domestic animal diseases

- is potentially a vector of diseases

- is capable of dispersing widely within short periods

- is a highly effective colonizer

- has potential as a food competitor

Conservation action

Conservation measures include re-establishing extirpated populations, establishing protected areas with strict law enforcement and exclusion of livestock, and developing monitoring programs. Concerning introduced Aoudads: In some cases, they should be eradicated or controlled to limit negative effects on native fauna and plants. [16]

Algeria: Aoudad occur in four protected areas in this country: Belezma, Tassili n’Ajjer, and Ahaggar National Parks, and in Djebel Aissa State Forest (De Smet 1997). [6] Priority conservation measures proposed in Algeria include:

1) Establishing more reserves in the north if the species is to survive in the Saharan Atlas range;

2) Reintroducing Aoudad into Djelfa Hunting Reserve (20.000 ha; est. 1974) located in the Haut Plateau (34°40’N, 3°15’E),

and into Tlemcen Hunting Reserve (400 ha) in north-west Algeria between Oran and Oujda (34°52’N, l°15’E). [6]

Chad: In Chad, Aoudad are present in the Fada-Archei Faunal Reserve (La Reserve de Faune de Fada Archei) in north-eastern Chad (established 1967). Unfortunately, conditions have been difficult in this region since 1972, as a result of political instability and the conflict with Libya. Poaching in the reserve probably takes place and there are military personnel stationed at the nearby town of Fada (Mekonlaou and Daboulaye 1997). Priority conservation measures proposed in Chad include:

1) carrying out surveys in the Tibesti and Ennedi mountains, and elsewhere to determine current numbers and actual distributions;

2) consider establishing a protected area, preferably a national park or at least a faunal reserve, in the Tibesti mountains;

3) improve the levels of protection, especially anti-poaching efforts, staffing and support for Fada-Archei Fauna1 Reserve, as with other protected areas in the country. [6]

Egypt: Aoudad have recently been confirmed as occurring in Gebel Elba Conservation Area (48.000 ha; est. 1986). Assiut University Protected Area was originally set aside in the 1930s to protect Aoudad, but there are no recent reports of the species’ presence (Amer 1997). Conservation measures proposed in Egypt include:

1) survey areas previously known to be inhabited by the species;

2) evaluate the habitat along with the potential for re-introductions. [6]

Libya: It is not known whether Aoudad are protected by law. The species was introduced into Tripoli Nature Reserve (870 ha; est. 1978). It may also occur in Jabel Nefhusa Nature Reserve (20.000 ha; est. 1978) in northern Libya in the Jebel Tarabulus range of the Jebel Nefhusa mountains (Tripolitania Region 32°N, 12°50’E), although this reserve does not appear to fall within the suspected distribution of the species (Shackleton and De Smet 1997). There are captive populations in Sabratha, Surman and the Zoological Garden of Tripoli (T. Jdeidi pers. comm.). The latter definitely belongs to the subspecies A. l. fassini. A population survey is needed to determine the current distribution and status of Aoudad in Libya. [6]

Mali: Aoudad receive no protection nor occur in any protected areas in Mali (Lamarche 1997). Proposed conservation measures include:

1) conduct censuses and surveys to determine population numbers and distribution within the Adrar des Iforas;

2) consider the feasibility of establishing a protected area for Aoudad in this region. [6]

Mauritania: Aoudad occur in one protected area in Adrar Mouflon Partial Faunal Reserve (Lamarche 1997). Conservation measures proposed include censuses to determine current numbers and distribution. [6]

Morocco: Aoudad occur mainly in four protected areas including: Eastern High Atlas National Park, Toubkal National Park, Takherkhort Hunting Reserve, Sochatour’s Tiradine Hunting Reserve

Aoudad also inhabit a number of other hunting reserves, most of which are so small that they are occupied only seasonally and have little significance for conservation of the species (Aulagnier and Thevenot 1997). [6]

Takherkhort Hunting Reserve is situated in the western High Atlas mountains (1.230 ha), was established in 1967 to preserve the species. Although around 350 to 475 animals occupy the hunting reserve (Mokhtari 2006), grazing by livestock is a serious threat. Animals from the reserve have been used for re-introductions to other areas, including Sochatour’s Tiradine Hunting Reserve. The native vegetation is evergreen oak forest, and the Aoudad is reported to be reproducing, and numbered around 70 animals in 1990. The most important conservation measures proposed include:

1) Surveys to determine the status and distribution of Aoudad in Morocco; 2) Increasing the number of protected areas. Among the most valuable and interesting natural places where Aoudad need protection, three or four national parks or permanent reserves can be proposed: Jbel Grouz and Jbel Maiz (arid hills near Figuig), Jbel Bou Iblane or Jbel Bou Nasser (eastern Middle Atlas), and some areas of rocky argan bush in the Anti-Atlas (between Igherm and Tata);

3) Hunting and grazing should be strictly forbidden in protected areas. [6]

Niger: All hunting has been banned since 1964 and though this law is enforced by the Nigerien Forest Service, the vast range occupied by the Aoudad, together with manpower limitations and political unrest, limit the effectiveness of anti-poaching efforts. Aoudad only occur in one protected area in Niger, in the vast Reserve Naturelle Nationale de L’Air et du Tenere, in north-central Niger. Created in January 1988, the reserve covers 7.737.000 hectar of Saharan desert and Sahara-montane habitat. The reserve may harbor as much as 70 percent of the total population of Aoudad in Niger (Magin and Newby 1997). [6]

Sudan: Aoudad fall under Schedule II as a protected species, though up to two can be shot by anyone with a class A or D license. None occur in any protected area in the Sudan (Nimir 1997). Conservation measures proposed include:

1) move Aoudad to Schedule I so that it is completely protected;

2) re-introduce Aoudad to remaining areas which are suitable. [6]

Tunisia: In Tunisia, Aoudad has been protected by law since 1966. A re-introduction of Aoudad into the Djebel Chambi National Park began in 1987, when ten animals, originally from Kasserine, were released into a one ha enclosure for later release into the rest of the park. Some of these animals escaped in 1988, and the wild population now numbers 100 animals (DGF 2005). A few animals are held in captivity in the Djebel Bou Hedma National Park, in the Bou Hedma ranges of the Atlas Saharien. Animals are also believed to occur in the proposed Dghoumes National Park (De Smet 1997), and the species was also released in the Oued Dekouk Nature Reserve, south of Tataouine. Priority conservation measures proposed include:

1) ensure the establishment of the new desert national park 50 kilometres east of Tozeur at Dghoumes (this area and the rest of the mountain chain north of the Chott El Fedjadj and Chott El Djerid, are considered good Aoudad habitat);

2) reconsider the suggestion to release Aoudad into Sidi Toui National Park because the topography is probably too flat to be suitable for them. [6]

Western Sahara – important conservation measures proposed include:

1) determine whether or not this species survives in Western Sahara, and if so, to ascertain its status and distribution;

2) establish a protected area for the species if there is a surviving population (for example, in Oued Ed Dahab Province);

3) Strictly control hunting and grazing where this species survives. [6]

Hunting

Aoudad hunting is presently (as of 2019-01) prohibited in most range countries. [2]

Chad: Hunting mostly takes place in the northeastern Ennedi Mountains in Safari concessions with licensed safari outfitters. [2]

Sudan: Aoudad can be hunted under licence (Kordofan Aoudad are included in Sudan Wildlife Schedule II as a protected species, though up to two can be hunted by anyone with a class A or D license.) [2]

Morocco: Since 1958, the annual ministerial order regulating hunting has severely restricted taking Aoudad. For example, in 1961 the species could be hunted for only three days, and only one day in 1966. Since 1966, the species is fully and permanently protected. [6]

Niger: All hunting has been banned since 1964. [2]

Spain, USA [2] – and Croatia – have thriving Aoudad populations, where controlled hunting is possible. [2]

Limited and strictly controlled Trophy hunting could be an effective option. It would provide incentives for Aoudad conservation projects and the locals to support Aoudad conservation. The current unrest in some of the range countries is, however, severely restricting sustainable use options. [2]

Nomadic people of the Sahara depended on Aoudad for meat, hide, hair, sinews (Sehnen) and horns and the species was considered to be of greater value to the economy of the Ahaggar Tuareg than any other type of game. [2]

Ecotourism

In most of the range countries like Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Sudan wildlife watching in general is (as of 2019-01) not or not a big factor.

Mammal watchers report Aoudad mainly from following locations in Morocco: Toubkal National Park, Tizi’n Test (huge enclosure), Eastern High Atlas National Parks, Cap Rhir, around Ouirgane. In Tunesia Djebel Chambi National Park seems the place to go.

selected trip reports

https://www.mammalwatching.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/VD-Morocco-Western-Sahara-2018.pdf

https://www.mammalwatching.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/VM-Morocco-2018.pdf

Literature cited

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[6] Cassinello, J., Cuzin, F., Jdeidi, T., Masseti, M., Nader, I. & de Smet, K. 2008. Ammotragus lervia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T1151A3288917. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T1151A3288917.en. Downloaded on 08 January 2019.

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[10] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain Monarchs – wild sheep and goats of the Himalaya. The University of Chicago Press

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.