The Portuguese ibex (Capra pyrenaica lusitanica) is an extinct subspecies of the Iberian Ibex. It was still numerous until 1800.

Names

English: Portuguese Ibex [2]

German: Portugiesischer Steinbock, Nordwestiberischer Steinbock [6] ((editor’s note: German new spelling rules, K 22: „Man kann einen Bindestrich in unübersichtlichen Zusammensetzungen setzen.“ Accordingly in this case it is advisable to use „Nordwest-Iberischer Steinbock „))

Portuguese: Íbex-português [Wikipedia], Mueyu [2]

Spanish: cabra montés cantábrica, portuguesa cabra montés [Wikipedia]

Taxonomy

Capra pyrenaica lusitanica, Franca 1909 [2]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms:

Capra lusitanica, Schlegel 1872. North Portugal [3]

Distribution

The Portuguese Ibex was related to the Pyrenean Ibex and occurred in Northern Portugal and throughout the Spanish provinces of Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria. Until 1800 this subspecies was still numerous. [6]

Iberian Ibexes, which occur today in Peneda-Gerês National Park, Portugal, belong to the subspecies Capra pyrenaica victoriae (Day 1981). [2, 6] They have been introduced from Gredos. Apparently a founder stock was strenghened with animals which escaped from the fenced re-introduction site in Serra do Xurés in Galicia. [2] Since 1998 they have been seen in a developing population (Moco et al. 2006). [6]

Course of extinction

As early as 1870 the form was very rare, and the last herd, consisting only of a few animals, was observed around 1886. In September 1889 a female was caught, however it died three days later. Two more animals were recovered dead in an avalanche. The last Portuguese Ibex died in its Spanish range in 1890 and 1892 in Portugal. The last sighting of a female was made in the vicinity of Lomba de Pau in Serra do Gerês (Maas 2011a). [6]

The main reasons for the disappearance of the Pyrenean and Portuguese Ibex – and the falling numbers of the two other subspecies – was undoubtedly indiscriminate hunting in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the expansion of livestock grazing and agriculture into remote mountain areas. [2] Portuguese Ibex were hunted for their meat, hides, trophies and particularly the bezoar stones, which were sought after in general medicine (Maas 2011a). [6]

Preserved specimens

Sanchez-Hernandez describes the Portuguese Ibex in „Tras las monteses de Sierra Madrona (2010) and shows a photograph of a fine full-mounted male specimen from the museum in Coimbra, Portugal. [2]

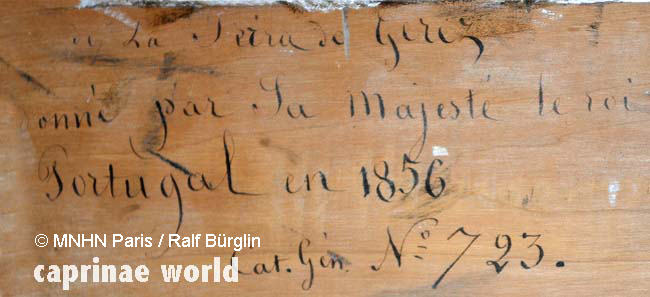

The Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris keeps a mounted male [seen by the author]

Description

Only a few measurements are available.

Various authors agree that there is a north-south cline in Iberian Ibex concerning body size, with heavier specimens in the north [2, 3]. Engländer (1986) provides figures of Iberian Ibex subspecies to show that there is a progressive reduction in size from north to south [3] – see table 1

How the Portuguese Ibex actually fits in this north-south-picture is not clear: Engländer (1986) lists the Portuguese Ibex as the second biggest subspecies [3]. Damm and Franco (2014) write that the Portuguese Ibex was „probably the smallest Ibex on the Iberian Peninsula“. [2] Matschei (2012) concludes that Portuguese Ibex (C. p. lusitanica) and Pyrenean Ibex (C. p. pyrenaica) correspond in size. [6]

Caption at the bottom of the specimen from Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris: „La Serra de Geres_Donné par La Majesté le roi_Portugal en 1856“ . Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Table 1: body lengths of Iberian Ibex subspecies

| subspecies | scientific name | body length (cm) |

| Pyrenean Ibex | C. p. pyrenaica | 148,0 |

| Portuguese Ibex | C. p. lusitanica | 142,0 |

| Victoria Ibex | C. p. victoriae | 135,5 |

| Hispanic Ibex | C. p. hispanica | 121,0 |

head-body: 142 cm [3]

shoulder height: approx. 70 cm [2]

Colouration / Pelage

Matschei (2012) quotes Cabrera (1914) in writing that the pelage of male Portuguese Ibex (C. p. lusitanica) is rather brown with fewer black patterns compared to other subspecies. It resembles the Hispanic Ibex (C. p. hispanica). [6, 2]

Matschei (2012) sees two clines referring pelage contrast in Iberian Ibex, one increasing from south to north, and one increasing from west to north. Therefore he sees the Portuguese and Hispanic forms as the most unremarkable, and the Pyrenean Ibex as the most conspicuous subspecies. [6]

Horns

Lydekker (1913) writes about the horns of the Portuguese Ibex: „… apparently less divergent than in other races.“ De la Zubia (1969) says that the horns of the Portuguese Ibex were relatively short with a narrow spread.

For Matschei (2012) the Portuguese Ibex differs most conspicuously in horn length and form. He also finds the horns are relatively short and less laterally curved. [6]

Horn length, male: 36 cm (of the typus form); 48 cm (specimen from the Coimbra Museum) [6]

Horn length, female: 18 cm – also very short: [6]

Capra pyrenaica lusitanica; same animal as above. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris

Literature cited

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC InternationalCouncil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[3] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[6] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag