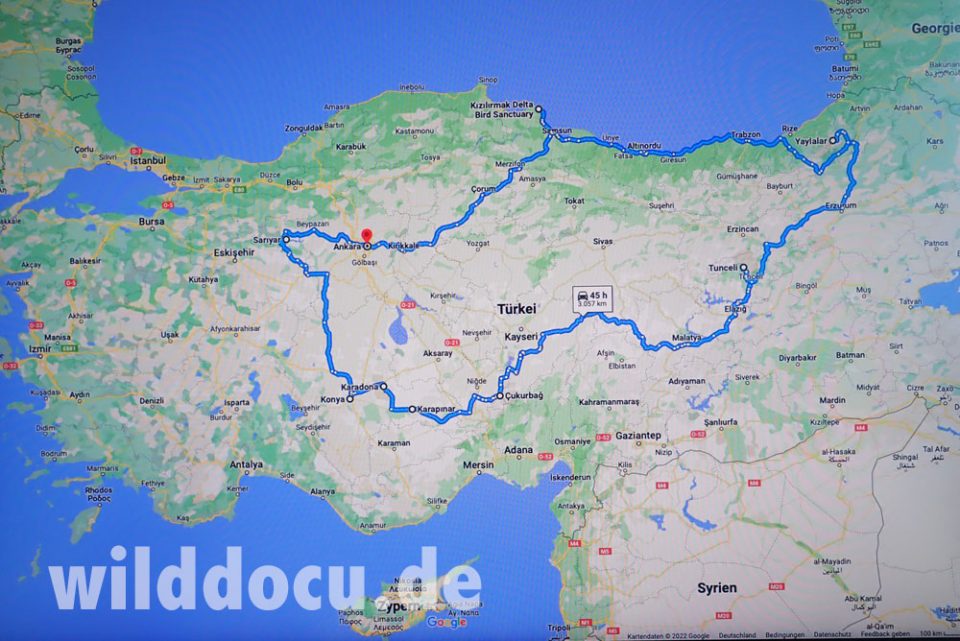

During the last week of October and the first week of November 2022 I did a 3000 km road trip through Anatolia. My main goal was to find Anatolian Mouflon, Wild Goat and Anatolian Chamois. Despite the unfavourable season several more species were on their way.

Saturday, 22.10.: Ankara – Sariyar

I start from Ankara Airport with my rental car. It’s a 2,5 h drive to Sariyar, west of the capital. This place had come to my attention, because Anatolian Mouflon had been released in the area recently. Near the village is a dam with Sariyar Baraji, a reservoir. What catches my eye instantly is the mass of birds on the reservoir.

And where there are birds, there must be mammals too!

First I ask the locals for my best chances to see the mouflon and I am directed towards a road, that leads alongside a ridge. Since the road is off limits to cars, I start to walk it in the afternoon. The mouflons I don’t find, but two big stray dogs. I am not really a friend of stray dogs. I pass unnoticed and get dinner at a picnic area, where I can also pitch my tent.

Sunday, 23.10.: Sariyar

I make an early night drive, find a European Hare (Lepus europaeus) and two Red Foxes while it is still dark. Then, the sun is alrady up, I find two more foxes. One of the two is this beautiful chap. Marvellous!

I get an invitation for a boat ride up the river to see the mouflons. (I don’t write down my guide’s name for reasons mentioned below. Let’s call him M.) After a few kilometers we get off the boat and climb the shoulder of a little canyon. M. asks me, if he should fire his rifle to let the sheep break cover. I tell him that I think that this is not appropriate. Instead he throws some stones into the gully – without success. I try to explain that in the future other wildlife watchers would appreciate a less invasive approach. I am not sure, he gets the message… We try another site, again without detecting any mammals.

After some glasses and cups of tea and coffee we decide to go on another boat trip and search for more animals at night. Right from the beginning I see five, then six spots in my thermal imager on the opposite bank. The diesel engine of our boat is as loud as loud can be. Nonetheless we get close, and just when I turn on my flashlight, six Wild Boars (Sus scrofa) take off and leave the bank.

Further up the river – about 10+ km from the next settlement – we see the first of four cats.

Other than the boars the cats seem unfazed. Of course I hope to detect a Caucasian Wildcat (Felis silvestris caucasica). According to Wuest et al (2020) this subspecies shows all characteristics of the European Wildcat, but is “supposedly less striated”. At first glance the first one looks like a good candidate, but then I find the lateral stripes are too contrasty and the tail tip is not broad enough. The next two are clearly house cats. The fourth one appears to be big and shows no lateral stripes at all. But I never get to see other details clearly. Later a Caucasian Badger (Meles meles canescens) and a Golden Jackal (Canis aureus) scramble up the slope.

On the way back I have a chance of a lifetime to see Maral (Cervus elaphus maral) at very close range. There is a female with a calf and a beautiful stag.

Diagnostic features of this Red Deer subspecies are a light belly (seen in the female), a dorsally extending rump patch and antlers with less distal branching than in west European deer (the shadow from my flashlight is actually doubling the number of endings.)

Back in camp we discuss our experiences. When I mention that at home I also hunt for the pot, the general sense of M’s reply is: “Oh, why didn’t you tell me before, we could have hunted the deer together.” … I believe this typically shows the attitude of some of the rural people. Hunting for the pot is a tradition. Poaching is not a subject. There is no sense of guilt, hence there is also no reason to not talk about it with a guest. I am sure Sariyar will have more visitors and especially mammal watchers in the future. For my very hospitable host M. it won’t be a problem to guide people to see wildlife the one day, and go hunting the next day. I have witnessed this in other countries and therefore I am sure: Simply establishing wildlife watching does not prevent poaching. It needs rangers to control the laws.

Monday, 24.10.: Sariyar

I start hiking at 5 am towards the area, where we tried to see the mouflon from the riverside. At sunrise I am at the right place, but despite much scanning nothing comes in sight. I am back for breakfast at 9:30 am. I sit at the riverside, sip my Turkish coffee and enjoy the tranquillity and warm sunrays. I can’t believe it’s the end of October.

While I later pack my stuff, I notice a Wild Boar and a Golden Jackal on the opposite bank.

The animals are 700 to 1000 metres from my view point. (I later measure the distance in Google maps, but am not sure about the exact position, where the animal stood. But 700 m is the minimum distance.) But what are the animals doing here?

The littoral zone of Sariyar Baraji is overloaded with dead, finger-long fish and young frogs.

According to the locals this happens every fall (why?). I can clearly observe through the ocular of my camera (800 mm lens attached) and derive from the behaviour and movements of the jackal that it is feeding on something at the edge of the water. At one point it is even leaping right into the water. Discussing it with the locals, they tell me that not only Jackals, and Wild Boar but also bear benefit from the fish carcasses. The leap of the jackal might have even been directed at a frog.

Then it’s time to say good bye. I won’t forget the hospitality of the people here. Next stop: Konya.

Tuesday, 25.10.: Konya – Bozdağ Milli Parkı

Until recently the Bozdağ Hills have been the only remaining place, where Anatolian Mufflon (Ovis gmelini anatolica) survived. When you look at a Turkey map these hills clearly stand out east of the megapolis Konya. On the other hand this area is just a tiny fraction of the original mouflon habitat. At one point countless millions of these wild sheep must have lived in the Anatolian steppe.

On my arrival I am surprised to learn that all what remains is a 40 m2 fenced enclosure – and visitors can’t just get a ticket at the entrance and enter the area. You have to apply for it at an office in Konya (Orman Ve Su İşleri Bakanlığı 8. Bölge Müdürlüğü. Address: Toprak Sarnıç Mh, Sapanca Sk. Pk: 42090, 42090 Meram/Konya, Turkey; phone: +90 332 322 68 72)

I am not sure, if I want to do that. So I leave it open and spend the next hours driving the roads at the base of the hills and scan the area across the fence. I choose the eastern slopes first.

The villagers in the settlements I pass trough, are really poor. So I understand why the fence is necessary. I read that officials also killed all the wolves inside the fence to enhance population growth.

In the afternoon I switch sides – and here they are on the Western slopes, female mouflons and their young, some actually very close to the administration building, I had visited in the morning.

The animals react like in a hunted population and it is not easy to get close, 400-500 metres is the closest. (Actually the Turkish Ministry of Environment and Forests issues a restricted number of hunting permits within the fenced area). A few photos come off. And I am happy with that. I drive on towards Karapinar.

Just as I start a young Anatolian Red Fox crosses the road: Like the fox I photographed at Sariyar it is very light-coloured. The ears are big as well. So my first thought is: Rüppell’s Fox! Checking the distribution map of this species, I find that it does not occur in Turkey, but in neighbouring Irak and maybe still in Syria. So I think, mammal watchers, who travel in the south of Turkey, should keep in mind that a Rüppell’s Fox might become a possibility in the future. To tell the two species apart, think of the ears of the Rüppell’s Fox, which are reeeally big.

Upon arrival in Karapinar I learn another lesson concerning Turkish hospitality: I can’t find the hotel that I had picked out on mapse, so I park my car and ask the next shop owner. He tells me “no problem” and grabs his phone. He calls a friend who is the owner of another hotel. Five minutes later the friend shows up and enters my car. He directs me to his place and I get my room. Of course flexibility helps to enjoy the situation …

Wednesday, 26.10: Karapinar – Demirkazik

It’s just a 2 h drive to my next destination at the base of the Taurus Mountains.

Shortly before arriving I discover a roadkilled hedgehog on the side of the road – a Southern white-breasted Hedgehog. Could it be that they are still not hibernating? I find out later.

I check in at Şafak Pansiyon, Çukurbağ. People are busy harvesting apples in the garden. My new host is also involved. But that is no problem, because the first thing I hear, when I get out of the car, is a squirrel. The room can wait. The nagging can only come from a Persian Squirrel (Sciurus anomalus). Fellow mammal watchers have pointed out locations in Turkey to just see this one species. Should I just be given this gift in passing by? Yes!!

It is a wonderful warm day. I get my mattress, spread it out on the lawn, and lie flat with the camera on my chest. It’s difficult to get good pictures while the squirrel is perching between the branches. It doesn’t need to move much either, because the seeds are available in abundance. But every now and then it stretches and its small body is bathed in sunlight. Only then does its unusual coat colour of orange and silver-black become apparent. What a beauty!

There are only three native tree squirrels in Europe (Tribe Sciurini – deutsch: Baumhörnchen): Eurasian Red Squirrel, Calabrian Black Squirrel and the Persian Squirrel – all in the genus Sciurus (deutsch: Eichhörnchen). The Persian Squirrel (Sciurus anomalus) – also called Caucasian Squirrel – should really be called „Turkish Squirrel“, because within Turkey it has its widest distribution. (The Turkish name „Anadolu Sincabı“ – Anatolian Squirrel – I find also not appropriate, because the species occurs not only in Anatolia - Asian part of Turkey - but also in the European part. Furthermore in some definitions of Anatolia the southeast of Turkey is not included, where the Persian Squirrel also occurs.) In Europe the species is distributed in an area called “Velika / Kırklareli” close to the Turkish-Bulgarian border and in “Belgrad orman” (Belgrad Forest),north of the European part of Istanbul (introduced), the Greek island of Lesbos (introduced) as well as in Transcaucasia (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia – the affiliation of these countries to the continent of Europe is still disputed). There is no denying that Sciurus anomalus is one of the prettiest squirrels.

I have a scare because I notice that I have forgotten my mobile phone cable in the last hotel. I’m already considering how far I’ll have to drive to get a new one. But then my host tells me that there is a phone shop in the next village. And I realise: Where every shepherd has a mobile phone, every village must have a phone shop. And it is exactly like that.

Then I go exploring. Tomorrow I want to go hiking in the mountains. Therefore I want to find out where I can safely park my car. My host also points out a site near Demirkazik village, where Asia Minor Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus xanthoprymnus) are supposed to occur. I can’t find them. During the rest of the trip I see more suitable habitat, but now ground squirrels. They must already be in hibernation.

Then I discover the mound of a Nehring’s Blind Mole-Rat (Nannospalax xanthodon) directly on a dirt road.

I remember Jan Ebr’s report on mammalwatching.com and how he got to see his blind mole rat. He writes: “At the end of the day, we managed to get a glimpse …” The “end of the day” doesn’t really motivate me at first, because I imagine that he waited quite a long time. But after stumbling over dozens of piles in the past few days, I think it’s now time to open a burrow. With my hiking boots it is no problem to push the earth mixed with stones to the side. And I’m lucky because on my first try I manage to uncover the tunnel without burying it. (I try a few more times later and find that it’s the rule rather than the exception that the ejected material falls into the burrow. Then you can use a small stick or spoon and try to uncover the hole.) Then have your camera ready and wait. You can expect the mole rats to come and close the burrow again. In the literature you find notes like: „rudimentary eyes hidden under a membrane“ and „Spalacinae mole-rats are truly blind“. But the question I ask myself is: If they are „truly“ blind, how do the animals notice that their burrows are open. I suspect there are only two options. Either the animals feel a draft or they are NOT truly blind, but can perceive light and dark. I count on the second assumption and use my flashlight to additionally illuminate the hole. And what can I say? It takes less than a minute and two different individuals appear at the edge of the burrow. Maybe the clicks of my camera cause them to quickly retreat back into their burrow. Nevertheless, I get a few shots in my box.

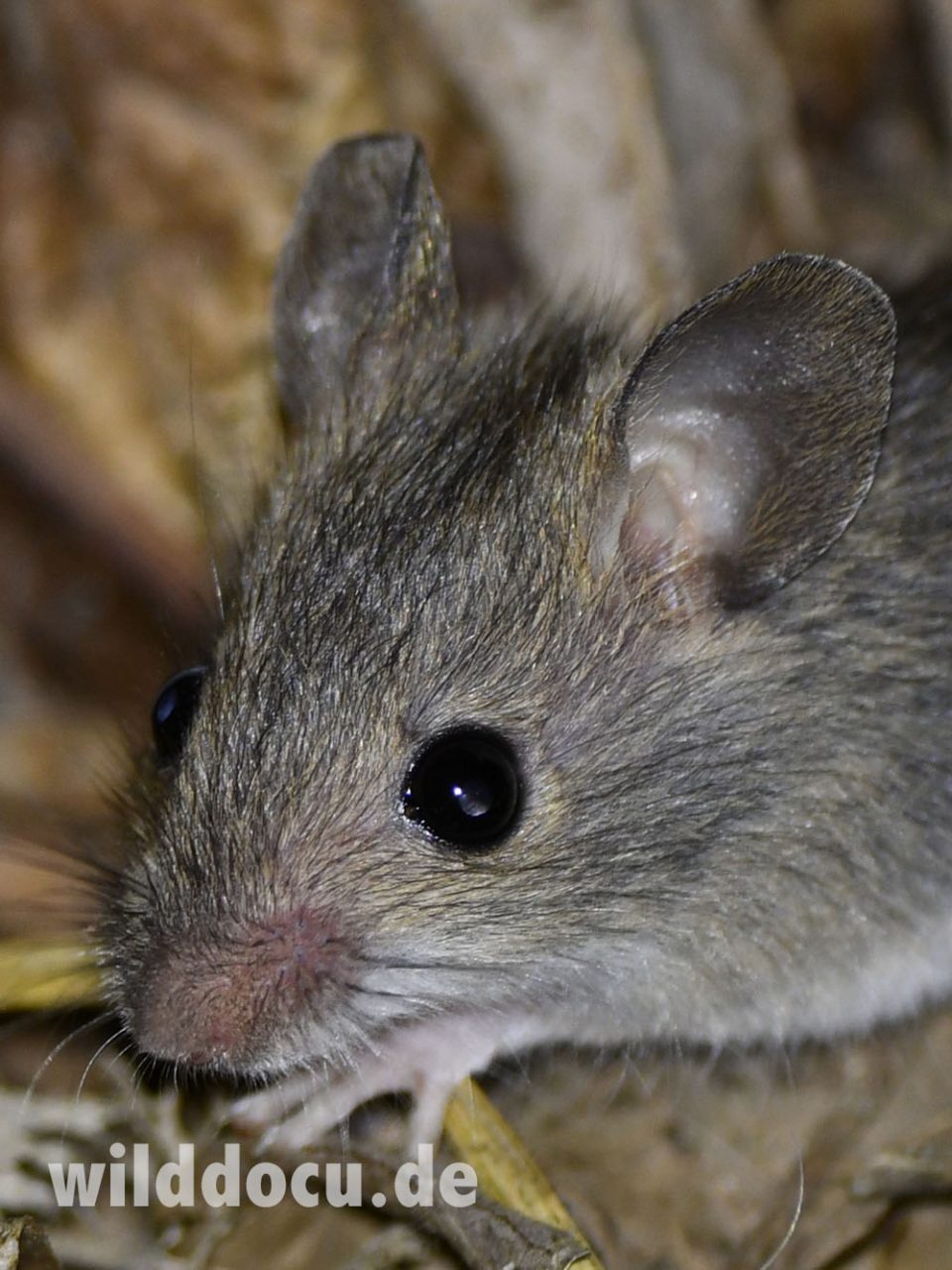

After dinner I take another walk through my host’s garden and the adjacent orchard and find this cute little mouse. Note the golden hair around the eye and on the ears!

At first I believe it is an Eastern Broad-toothed Field Mouse (Apodemus mystacinus). Later at home I contact Prof. Boris Krystufek, author of the “Mammals of Turkey and Cyprus”. He thinks however that the animal is more likely a young Steppe Field Mouse (Apodemus witherbyi) – this would explain the buffy hair (start of post-juvenile moult).

Thursday, 27.10.: Aladağlar National Park

Before breakfast, I want to find the Persian squirrel during its main activity period again. I make a direct hit: As I enter the garden the squirrel is there on the ground and I can admire it in all its glory.

When I probably get too close to it, it doesn’t look for cover in a tree, but between rocks. Only when it no longer feels safe there does it retreat to a walnut tree. I later read that they are in fact considered less arboreal than Eurasian Red Squirrels.

Then I’m ready for a one or two day hike in the mountains to find Wild Goat (Capra aegagrus). I park the car at the exit of the gorge in Demirkazik (the village; the highest peak in the region bears the same name). The gorge is grandiose and a real change to the brown steppe of the past days. The path is quite demanding with some small climbing passages. After about three hours I reach the so-called base camp, which is actually a shepherd’s camp. Here I put my rucksack down, lie down with my head in its shade and use my binoculars to search the slopes for goats. A small herd with females and young is quickly found. I keep looking very persistently, but I can’t find any males. I assume that the domestic sheep and dogs will arrive later and therefore do not want to set up my tent here. Also, the plan is to climb up to the goats and photograph them either today or the next morning.

At 2520 m I find a very nice spot at the foot of a wall. There isn’t enough space to set up my tent, but that’s not even necessary because the air is very dry and this time of the year there are no mosquitoes around.

Only with the camera in my luggage do I climb further up. The terrain is so rugged that I can get up to about three hundred meters from the goats unnoticed. The light is also perfect, and that’s how I get quite useful pictures. The goats are beautifully marked, with a reddish brown base color.

You can’t avoid them seeing you at some point. They don’t whistle to warn, their warning call sounds more like a croak. When they’re gone, I survey the site at about 3.000 metres and find the droppings of a large bird that can only come from a Caspian Snowcock (Tetraogallus caspius), another species that’s high on my target list.

At 6 pm it’s dark. Lying in my sleeping bag, I talk to my wife on the phone. Down in the village the muezzin is calling. Shooting stars are shooting above me. There is no better way to end a day in the mountains of Turkey.

Friday, 28.10.: Aladağlar National Park

The night is tolerable. But I had chosen the wrong sleeping bag when packing, the one I have with me is actually not warm enough for this stage of the journey. At night I put my trekking pants back on to be able to continue sleeping without freezing.

The morning begins with one of the most spectacular bird observations I’ve ever done: I’ve just crawled out of my sleeping bag, when I hear a kind of whistling. Fractions of a second later, the whistling has increased to – what I almost want to call – thunder, and two dark balls are shooting down from above, twenty, thirty meters past me and down towards the foot of the mountain. Down there I can see that the balls also have wings, that now give the balls a different flight direction: in a curve parallel to the slope and finally up the slope a little. I have already seen black grouse, alpine choughs and peregrine falcons in the mountains, which also came down from above and made a spectacular flight noise. That’s why I’m only shocked for a moment and immediately combine: That must have been two Caspian Snowcocks. But the impression left by the noise won’t let go of me that quickly. This is genius. I climb around the next rocky corner, look up and hope: Maybethere are more coming.

I hear flute sounds. I pull up my bird guide app, read and listen: „The song … curlew-like from a distance, mostly at daybreak …“ No doubt there are more snowcocks perched up there somewhere.

And it only takes a few seconds and I spot two birds silhouetted against the slowly turning blue sky at the highest peak I can see from down here. And then again it’s only fractions of a second, and I witness a spectacle that will motivate any hesitant wingsuit base jumper to do it after all: one of the chickens jumps off, headed straight for me – as it seems. Spread wings are not visible. The trajectory is that of a tossed frozen chicken. And then the whistling again, the thunder, and then it is shot past me. Only now do I have the camera up and look through the viewfinder. The bird spreads its wings, glides away to the right.

The shutter clicks a few times. A single image is sharp. Not the best of pictures, but a very rare nature document: a Caspian Snowcock in flight. Wow, what a wild chicken show!

Breakfast hunger and thirst is coming up. I descend to the „base camp“ with its water troughs – and find that the water is frozen. I pull the hose out of the ice hole. The water appears to have frozen in there too. There is not a single drop. I don’t want to break the ice in the trough to get to the water underneath, so I have to descend to the gorge entrance to draw water from the creek there.

Then I climb up to the pass on the east side of Mount Demircazik. It’s hot again. On the way I put my head in the shade of my standing backpack and scan the slopes. At first no other Bezoar Goat can be found anywhere. Only from the pass do I discover a herd of around 20, which also includes some males.

But the animals are on the other side of the valley and must be at least at 3500 meters, unattainable for me today. It would take me another day to get up there. I don’t want to that this time. So I descend.

Again I hike through the gorge. Seen from above, everything seems even more spectacular to me. In several places, the gorge walls narrow to a few meters. Sometimes it’s scary tight. What you don’t need here is an earthquake.

After the key spot, which requires a five meter climb, there is an outlook to the shoulder of the gorge, where three more Bezoar goats pass by. One of the animals is a young male. At a distance of estimated 400 meters, I get quite usable pictures. The chance of seeing the wild goats while hiking through the gorge is probably very small, the views onto the shoulders are too rare. I just got lucky. Of course, the goats do also have reason to climb to the bottom of the gorge (green stuff). But the busier the canyon is, the less often this will happen. I arrive at my car quite exhausted.

In the pension there’s first tea, later dinner. During my nightly rounds with the thermal imager, I discover a mouse, but I can’t identify it in the light of the flashlight. In the orchard I track down a Red Fox, which complains with a hoarse bark.

At the entrance / exit of Çukurbağ there is a sign that welcomes visitors and says goodbye. Two goats are shown left and right. One animal represents a Bezoar goat, the other an Alpine ibex. Hä? Alpine Ibex in Turkey??

The English Wikipedia lists the species Capra aegagrus as „Wild Goat“, but the subspecies Capra aegagrus aegagrus as „Bezoar Ibex“ – which is a completely different name. I don’t know if that’s generally the case in English. There are also two different names in Turkish. Maybe that’s why people think of two different species.

The case also shows that we seem to know so little about our world of large mammals. Some officials choose an exotic species from another continent to promote their region – and no one seems to notice or care.

Saturday, 29.10.: Aladağlar National Park – Sultan Marshes National Park

It is only an hour’s drive to the Sultan Marshes. When I arrive at Sultan Pension, I am told that: “It is not possible to be in the area without a guide.” After I mention that I would like to stay in the guesthouse, it is possible …

Of course, this isn’t the best time of year for birdwatching, but two lifers pop out when walking the boardwalk: a Bearded Reedling (Panurus biarmicus) and a Moustached Warbler (Acrocephalus melanopogon). Very pretty! At the beginning of the boardwalk Wild Boar have created a trail through the reeds.

I have lunch at the pension and then drive to the area where Jan Ebr observed William’s Jerboa, Tristram’s Jird and a Marbled Polecat just this spring. The semi-desert mentioned in Jan’s report begins north of the village of Karacaviran (when coming from the south).

This biotope is the last remnant of original vegetation. Everything around it has been converted into agricultural land. As long as it’s still light, I explore the area and estimate which dirt roads I can manage with my car. I’m less scared of getting a flat tyre than of sinking in the dust. In the end I’m fine.

I wait for the night and then – nothing happens for a long time. It can be assumed that the jerboas are already in hibernation. Seeing a polecat is almost always a matter of luck, but a jird at least – not such a consistent hibernator as the jerboa – should show up. And at some point I see something flashing in my thermal imager. I get out of the car and walk about 100 meters into the semi-desert. The thermal image stays steady, and when I finally turn on the flashlight, it’s actually crouching there, a Tristram’s Jird (Meriones tristrami). A great guy! And I can get good pictures of it.

Back at the car I have to get along with three boys who must have seen my flashlight from the village. I show them my equipment and present them images on the display of my camera. That lets them become relaxed – at least two of them. If I could present a tiger, I guess, I would be more convincing. Experience has shown that with a rodent it is not so easy to win somebody over …

That reminds me of the Marbled Polecat (the translated german name for it is “Tiger polecat” – Tigeriltis). I try to use the translator to make clear that this is actually my target. One of the guys says he has one upstairs. I guess, we have a problem with the translation, I laugh and say that I think that this is another animal, a Stone Marten. Anyway, the conversation is relaxed now, and then the guys don’t get surprised when I say I have to keep looking for more animals. But since I’ve already been on duty for a few hours, I now had for my pension.

On the way back, a mongoose jumps across the road (at 38.156403, 35.375608). I only see the silhouette though, but the pointed snout and tripping steps let me be sure that it is a mongoose. Wikipedia keeps a “List of mammals of Turkey”. There you find the Egyptian Mongoose and the Indian Gray Mongoose. However, according to Özkurt (2015) “the Egyptian Mongoose is the only member of the family Herpestidae in Turkey”. Özkurt further writes that the Egyptian Mongoose “was distributed in the Mediterranean and Aegean regions before the 1970s”. However Özkurt recorded the species only from “Hatay, Osmaniye, Adana, and Mersin, in the area between Hatay and Silifke”. I found “my mongoose” about 100 km north of Özkurt’s northernmost find-spot.

Sunday, 30.10.: Sultan Marshes National Park – Tuneli

It’s still dark, when I’m back on the boardwalk. It’s bitterly cold, the water between the reeds is partly frozen. At the first lookout I photograph a kingfisher. I didn’t have that species yesterday. I watch the sunrise from an observation tower diagonally opposite my hotel. At the foot of the tower there are mole-rat hills. A hole could lead to the burrow of a jird. After breakfast off I go towards Tuneli. The country seems to become more and more lonely towards the East. Ornithological highlights are a Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) and a young Bearded Vulture (Gypaetus barbatus).

I reach Tuneli only after dark.

Monday, 31.10.: Tuneli – Munzur Valley – Ovacik

Early in the morning I drive the 50-kilometer route through the Munzur Valley and the national park of the same name, which is said to be „the largest and most diverse national park in Turkey“.

En route, eight Bezoar Goats stand by the side of the road and lick dust.

After the shy animals in Aladaglar and the effort I made there to get close to the animals, this is really a laughing stock now – but of course also a great opportunity to be close to the animals. The animals become nervous, when cars approach and run up the bank. But they don’t mind my presence. Poaching seems not to be a problem here. Furthermore I see a hare, a fox and up in the mountains a first but unexpected herd of Anatolian Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica).

After arriving in Ovacik I enjoy a coffee and two pieces of baklava. I just wanted to use the morning to look for animals while driving through the valley and then continue driving. Now I realise that I haven’t checked the route carefully enough on my app: In order to get further north-east, I have to go back through the Munzur Valley to Tuneli. On the way out I get a message from my next host at Kackar Dagi that he made a mistake and the accommodation should cost 40 instead of 30 euros. That annoys me. I spontaneously decide to extend my stay here by one day and organize a hotel. I turn around and take a hitchhiking vegetable retailer back to town.

Then I set off into the mountains, where I had previously seen the chamois. There even seems to be a dirt road leading up to the chamois. I park my car and want to try walking up the road. However, I make the wrong decision. The path I have taken does not lead to where I want to go, but to a side valley from which there is no possibility of getting to the other route. It is already too late to correct the mistake. I’m just hoping for new discoveries in the valley I’m in.

I unearth a cracked turtle shell, a wolf scat and a bear scat. But there are no other chamois. Back in the village I visit my friend from the greengrocer’s shop, who invites for a cup of tea. Of course she does, everybody in Turkey invites you for tea! Great country!!

In the evening I drive to Munzur Gözeleri. I don’t quite understand what people try to explain me, but I figure that there is the source of Munzur River. In fact there are creeks and pools, where the water seems to come to the surface. It is certainly also a destination for local tourists. But at this time of the year nobody is here. The habitat looks promising and I want to check what the night has for me.

My thermal detects a mouse, but I can’t get close. There are at least three bats, which I also can’t identify. There is a fox with a darker fur. There seem to be at least two subspecies of Red Foxes in Turkey: The Anatolian Fox (Vulpes vulpes anatolica) and the Trans-Caucasian Fox (Vulpes vulpes kurdistanica). Could this be kurdistanica? I also scan the slopes above the water in hope for a Wooly Dormouse, although I assume that for this species it must be to late in the season.

Tuesday, 1.11.: Ovacik – Munzur Valley – Kaçkar Pansiyon

I start at 4 am for the return journey through the Munzur Valley. On the way to Tuneli, seven Red Foxes run across the road, as well as a stately Wild Boar.

Shortly before the city, two canines cross the street 50 meters in front of me. I immediately have the suspicion that it could be wolves.

Where they have just crossed, I bring my car to a stop. I open the door, grab my camera from the passenger seat and turn the flashlight on: I see the second animal running in a gap between the trees. Both stop a little further behind trees and look back at me. I see their eyes shining in the light of my flashlight. In the corner of my eye to the right, something scurries past just in front of my car, one, two, three maybe four more animals. Of course they are Wolves (Canis lupus), no doubt, a whole pack. I lose track, can’t tell exactly how many there are, because I’m trying to catch the animals with my kamera – one after the other – in the gap between the trees. At the same time, I keep looking back at the wolves crossing in front of my car. There they are just five meters! away from me. Wow! The pulse goes up! As always on such occasions, the spook is gone within seconds. Pretty soon my mind turns on again and the question pops up: What is a whole pack of wolves doing on the outskirts of a town? One thing is certain: When wolves are on their way in a pack, they are after large prey. What comes into question are the big yellow dogs, which here, as everywhere in Turkey, roam around, supposedly without a master. And that’s why many of the dogs that have an owner, wear a spiked collar.

After Tuneli, the route is mostly on lonely country roads through spectacular mountain landscapes or along a reservoir basin.

Shortly before the town of Yusufeli a chain of newly built tunnels begins. For the first time I experience that my navigation apps fail completely. Eventually I realize I’m wrong, have to turn around and go back.

After digging my way through bustling Yusufeli, the road leads spectacularly upwards. Some of the sections are narrow and improvised. On the other hand, other sections have been expanded on a large scale. Apparently they have big plans here in the region… After two hours, countless curves, sublime views and the decision whether to drive into a dark tunnel from which it smokes, I finally arrive at my next accommodation. (The smoke turns out to be dust from a car ahead.) A few more metres in height and there is snow. Ismail, my new host, gives me a very warm welcome and we make good contact right away.

Wednesday, 2.11.: Kaçkar Dagi area

Before breakfast, which I order for 9 a.m., I take a little walk around to find my way around. In principle, you can already see the Anatolian Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica) standing on the slope from the dining room. However, there are only two at first, which I then find again outside – albeit way up. It is initially limited to that.

After breakfast I head west into the valley. After a kilometre or two, I discover a couloir on the right-hand side of the slope that leads up and that may give a glimpse of the area where the chamois stood in the morning. I decide to go up there.

At the bottom it is quite steep and rocky until I finally reach the edge of the gully. From there it goes on. Again and again I carefully look over the edges to discover my chamois. Unfortunately, they don’t do me the favour of showing themselves. But I’m not giving up hope and keep climbing.

Finally I reach the summit at 3024 meters. I could descend behind it to get to the valley north of the village. That would be a nice round. However, this north-facing side has so much snow that this route seems too dangerous. So I decide to descend on the route I came. And there is the next avian highlight: a Caucasian Black Grouse (Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi). It flies up from the ridge in front of me. Gorgeous!

I have to go very slowly in order not to risk a misstep. Finally, exhausted and without a photo of the chamois, but still happy, I return to the village. I keep myself busy with my camera with the old buildings; the cow dung hanging on the walls to dry and Ismail’s grandfather’s bezoar goat trophy.

More snow is forecast for tomorrow. To prevent getting stuck with my car, I take it down to the village, so that I don’t have to drive the steepest passages if the worst comes to the worst.

Thursday, 3.11.: Kaçkar Dagi area

I start with the first light in the north lying valley. In the second couloir to the left I see chamois marching. I don’t know if they have seen me yet. I turn around so that I am out of view. I climb up under the cover of the slope. There’s snow, but I can find good footholds. At several corners of the rock I carefully push my head up to be able to look over the edge. Only on the fourth attempt do I discover the animals. I crawl the last few meters on my belly, pushing my backpack in front of me to finally position my camera with the 500 mm lens there. At an estimated 400 meters, the distance is still very far, but still: the first pictures are in the box.

Visibility is getting worse and worse, so I withdraw again unnoticed. Bird of the morning is a Wallcreeper (Tichodroma muraria).

After a late breakfast I need a nap. Yesterday’s hike is still in my bones. Then I start again. The weather is no better. Nevertheless I still take the big pipe (800 mm) with me. Soon I reach the spot of the morning. The animals are still there.

Everything would be fine, but the visibility is miserable in the snow. The wind is blowing towards me, which is good, otherwise I wouldn’t have a chance to go unnoticed by the chamois. But that also means that the snowflakes accumulate on my lens. Cleaning it up isn’t that easy either, because I shouldn’t be moving at all because of the chamois. Finally it comes as it must come. An animal spots me, whistles, and all the chamois (8) look in my direction. However, since I am lying down and not moving a millimetre, the chamois‘ instinct to flee is not fueled. The Anatolian Chamois simply does what all chamois do in such a situation: They stop and stare in the direction of the supposed enemy – and wait and wait and wait. At some point I dare to look through the camera again: nothing. I pull it down to check it from the other side: full, full of snow. I have to cancel. Although the chamois still have their eyes on me, I slowly slide back until I am out of their sight. Completely sodden on the front, I arrive back at the pension at prime tea time.

Soon there is also dinner – sautéed chicken and vegetables, yoghurt soup, salads. Delicious to burst!

Ismail is very interested in wildlife viewing and my thermal imaging device. He tells me that yesterday around 10 p.m. he was still searching the slopes with a flashlight and discovered two pairs of eyes. He thinks they were bears. We agree to go watch again in the evening. In the end we only track down two or three mice, but can’t get any closer to them. We’re probably too early for the bears.

Friday, 4.11.: Kaçkar Dagi area

More snow. I decide to look at the second couloir again. As I climb, I notice that the snow makes the slope dangerous. There is a risk of slipping and crashing uncontrollably into rocks below. I first try to minimize the danger by preparing my steps with my boots before I finally stand on them. On the last 30 meters to the lookout, however, the situation gets so tricky that I don’t dare to climb all the way through. It’s too risky. As carefully as I climbed on, I descend and walk back into the village – back to the breakfast table.

The midday sun is shining brightly, giving me hope that the warmth will melt the snow on my slope. So: let’s go again! In fact, the situation on the second attempt is quite different. Most of the snow has melted and the ground underneath is soft. This is how clean steps can be set. I arrive at my vantage point, throw myself on my belly, crawl forward and… the chamois are gone. Probably yesterday’s excitement caused the animals to change location. I do that too, dismount and hike further north in the valley. I regularly stop and search the slopes without getting any more animals in the viewfinder. The mountains are silent, lonely and magnificent. Finally, I stroll leisurely back to the village. I sample the berries on each bush and ultimately agree with the bears: the rosehips, softened by frost and thaw, are the tastiest fruit in the valley (correspondingly, rosehip bear scats are the most common).

I spend another leisurely afternoon in the pension. Among other things, we talk about the shoes that Ismail’s grandfather wore on his game drives. Before the 1970s it was moccasins made of cowhide (without soles), then rubber shoes. It is unbelievable how the natives found their way around here with such primitive tools. According to Ismail, people first immigrated here from the Caucasus region in the Middle Ages.

The plan is to drive down into the valley in the late evening and find animals during the drive – preferably an Anatolian leopard ;-), which according to Ismail was detected here with camera traps last year. But unexpectedly it starts snowing again, which makes me restless. Cihat takes me to my car in the village, from where I drive on. It’s dark now, but probably too early to spot bears and other large carnivores. During numerous stops, I don’t detect anything.

I had asked Ismail to reserve a hotel in Yusufeli. But down there my navigation apps fail again. I don’t see a junction into town or overlook it. Then I drive back into the chain of long tunnels. When I finally get a signal again, I’m so far away from Yusufeli that I don’t want to turn back. I’m already on the road to Rize and after another long tunnel on the northern slopes of the Pontic Mountains. I’m still hoping for a hotel, but then I just pull up on a bend in a mountain road, throw myself on the back seat of my car and snuggle up in my sleeping bag for a short night.

Saturday, 5. 11.: drive along the Black Sea coast

The forest on the north side of the Pontic Mountains is lush and shines in all autumn colours. Here you could look for the Radde’s Shrew (Sorex raddei) and higher up for Robert’s Snow Vole (Chinomys roberti). I have a short time before sunrise, but from the moving car I can’t find a suitable spot to search for small mammals. On the lower slopes of the Rize region that’s where the crop areas for Turkish tea are. The coast itself is heavily populated. I drive all day to reach my final destination: the Kızılırmak Delta Bird Sanctuary. I spend the night in a hotel in Bafra.

Sunday, 6. 11.: Kızılırmak Deltası Kuş Cenneti

I am in the area early in the morning. Far before the protection zone, maybe half way between Bafra and the entrance to the bird sanctuary (ca. 10 km before the coast) I start looking for animals in the agricultural areas with my thermal imager. A Barn Owl (Tyto alba) shows me where the rodents are.

In various places, mice climb in herbaceous vegetation, which immediately climb down as soon as a ray of light falls on them. I’m assuming these are Harvest Mice (Micromys minutus). I do not manage to take pictures, but I see some of them briefly and would say they are very small and delicately built and too small for Apodemus. Later I read that this species is not mapped for Turkey – according to „Mammals of Turkey and Cyprus“. If I had known before, I would have tried harder to get a prove.

A Red Fox is on its way.

A young Southern White-breasted Hedgehog (Erinaceus concolor) perches on the side of the road.

A cat catches my attention. At first glace, it seems to be a good candidate for an Asiatic Wildcat (Felis lybica ornata). The distinguishing features are: many irregular dark SPOTS on flanks, head and limbs; a slim ringed tail with black tip; some horizontal streaks on upper part of leg; two parallel black bars on inner side of each forearm and deep brown tufts of hair on ear tips. Aside from the missing ear tufts, an Asiatic Wildcat can be simply ruled out by distribution: Asian Wildcats do not occur in the Black Sea region.

In the first light I detect my most wanted bird of the area: Grey-headed Swamphen (Porphyrio poliocephalus). These colours! Those long toes! Wonderful!!

Domesticated water buffalo wander around.

But there is something else! No doubt, there are also two Golden Jackals (Canis aureus). The plain is covered with huge rushes – probably Spiny Rush (Juncus acutus). They are actually so big that you can easily hide behind them as an upright person. So I creep from bush to bush, and when I’m about 100 metres from the jackals, I kneel on the ground and leave cover. One of the jackals is just disappearing. The second jackal spots me but doesn’t react. I can take pictures in peace. Finally one of the water buffalos takes an interest in me. I stand up – which causes the buffalo to stop approaching – and, unfortunately, causes the jackal to flee.

I continue marching along the road where a jackal comes towards me. (I suspect it’s the same animal.) In this situation, at 200 meters the jackal immediately recognizes me as a human – and supposed enemy – and runs off in the opposite direction. A little later, a group of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) trots parallel to the road.

These animals can also be photographed very nicely. I’m the first to walk in the area today, on a Sunday morning. And that seems to be paying off. Back at the entrance area, the rangers are now on duty. It seems there is not much to do for them this morning – except to invite me for tea, which I enjoy as always. Then I hit the road again. The Pontic Mountains seem to decrease in height towards the west. So I have no problem / no snow to cross the mountain ridge towards Ankara. I reach my airport hotel in the evening, being very happy with my 3000+ kilometre Türkiye circuit.

Literature

Kryštufek, B. and Vohralík, V. (2005): Mammals of Turkey and Cyprus. Univerza na Primorskem, Znanstveno-raziskovalno središče Koper Zgodovinsko društvo za južno Primorsko.

Önder, Özkurt (2015): Karyological and some morphological characteristics of the Egyptian mongoose, Herpestes ichneumon (Mammalia: Carnivora), along with current distribution range in Turkey. Turkish Journal of Zoology 39(3):482-487

Wuest D., Kitchener A., Ghoddousi A., Gerngross P., Barashkova A., Lanz T., Sliwa A., Krivopalova A., Shakula G.,Breitenmoser-Würsten C. & Breitenmoser U., 2020: Assessing the expediency of photographs to study the distribution of wildcats in southwest Asia. CatNews X, xx-xx. Supporting Online Material.

Schreibe einen Kommentar