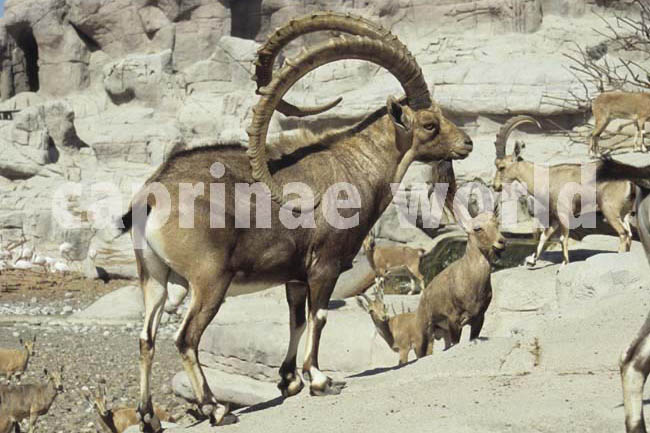

The Nubian ibex is a species that has adapted to desert environments (2). It is one of the Capra species with maximum shoulder height, at the same time it is one of the lightest. (3) The explanation is: it is more lightly built. (1) Horn length (up to 120 cm) can exceed those of the Alpine ibex. (2)

English common names: Nubian Ibex, Middle Eastern ibex (3)

German: Nubien-Steinbock (3), Nubischer Steinbock (4)

French: Bouquetin de Nubie (3,4)

Spanish: Íbice de Nubia (3,4), Capra nubiana (4)

Russian: Нуби́йский го́рный козё́л (1)

Arabic: Beden (1)

Hebrew: Je’el, Yael (1)

Amharic: Yenubeya (1)

Taxonomy

Capra nubiana (F. Cuvier, 1825)

Type locality: Egypt

In the past the Nubian ibex was classified as a subspecies of Capra ibex. Based on phylogenetic data, it warrants classification as a seperate species. Some authers declare it monotypic – with no subspecies (3,7). Groves and Grubb (2011) argue in support of two subspecies primarily on the basis of color: Capra nubiana nubiana from Sudan, which is darker, and Capra nubiana sinaitica from Israel and Sinai. (4)

Alpine ibex (left) and Nubian ibex (right): The Nubian ibex is taller, lighter (both in color and weight), has longer horns and black-and-white legs.

Typical for all ibexes, the Nubian ibex has also a spot of hard, hairless skin on the „knees“ – called „callus“. Photo taken at Al Ain zoo

Distribution / countries occurence

This species occurs in Egypt east of the Nile, north-east Sudan, northern Ethiopia and western Eritrea, Israel, west Jordan, scattered locations in western and central Saudi Arabia, scattered locations in Yemen, and in southern Oman. It is extinct in Lebanon and Syria (however, there is one introduced population). (5)

General discription

total length: head-body 119-160 cm (males), 90-120 cm (3)

shoulder height: 75-110 cm (males); 65-100 (females) (3)

tail length: 9-17 cm (males); 6-16 cm (females) (3)

ear length: 13-20 cm (males); 13-18 cm (females); ear longer than tail (3) and longer than those of the Alpine ibex (1,7)

beard: 7-10 cm, dark in older males (3)

weight: 50-85 kg (males); 25-40 kg (females) – males weigh 50 % more than females (3)

horn length: 88-127 cm (males); rarely longer than 35 cm (females) (3)

Life span: rarely more than 11 years in the wild (males) (3)

Groves and Grubb (2011) ascertain a cline in body size from north to south. Meile et al (2003) say that the lightest animals are to be found on the Sinai and the heaviest in Sudan. (6)

Coloration

General body color is pale brown to reddish-sandy. Chin, belly, and usually upper inside of legs and scrotum are white. In males in winter pelage, lower neck, chest, and upper front and sides of front legs can be black. There is a dark, mid-dorsal stripe from the neck to the tail and a well-defined or faint flank stripe. A silver saddle can develop in older males. In both sexes the rump patch is small, narrow, and white; tail is black and tufted (hairs 3 cm long); and dark front of legs and hooves sharply contrasts with white knees and pasterns. Females lack dorsal and flank stripes (3) and in Israel and Sinai are lighter in color. Specimens from Sudan are generally darker. (4) In late autumn, when the rut starts, and winter, the male’s neck, chest, shoulders, upper legs and sides become dark brown to almost black. (1) Summer pelage is short, smooth and shiny – supposedly reflecting solar radiation. (2)

Young Nubian ibex (C. n. sinaitica) male: The coat is relatively light. Photo taken at Al Ain zoo by Wolfgang Dreier

Mature Nubian ibex (C. n. sinaitica): The coat appears much darker compared to the young animal above. Photo taken at Al Ain Zoo by Wolfgang Dreier

This specimen shows the typical dark, mid-dorsal stripe that runs from neck to tail. Females lack the dorsal stripe. Photo taken at Zürich Zoo

Summer pelage is short, smooth and shiny – supposedly reflecting solar radiation. Winter pelage is less shiny. Photo taken at Tallinn zoo

Horns

Mature male horns diverge slightly and grow upward, scimitar-shaped, with the tips pointing forward. (3) Compared to European and Asian ibexes they have narrower horns. (7) The relatively flat frontal surface of male horns have up to 36 transverse knobs. In the first four year the horns can grow up to 20 cm per year. With the fifth year horn growth slows down. After the 10th year the increment measures only 2-4 cm. In years with less precipitation horn growth is slowed down. (2) In extrem desert environments the horn annuli are poorly pronounced and difficult to count. The largest horns ever recorded, 138,5 cm, come from a captive animal from the Khartoum Zoo. A wild specimen from the Red Sea Hills measured 129 cm. (1)

Male Nubian ibex (C. n. sinaitica) have maximum horn lengths exceeding those of Alpine ibex by 25 centimeters. Photo taken by Wolfgang Dreier at Al Ain zoo.

This young male is 1 year and 6 month old. Note the extrem horn growth. In the first four years the horns can grow up to 20 cm per year. Photo taken at Zürich zoo.

Habitat

Nubian ibexes occur from below sea level in the Dead Sea area to 2600 m in mountainous terrain interspersed with rocky wadi beds (riparian areas), cliffs, escarpements, boulder-strewn scree, and plateaus in proximity to precipitous escape terrain. Annual precipitation can be less than 70 mm and daytime temperature can exceed 40°C. Springs, natural water catchments in canyon pools and riparian areas are important watering sites and the associated vegetation is an important food source. (3)

Females not accompanied by kids select richer feeding areas, spend more time feeding, forage farther from precipitous escape terrain, and associate in smaller groups than females accompanied by young. Females with kids probably prioritize minimizing risk predation to offspring by adopting a conservative behavior strategy, expecially by remaining in proximity to rough, steep, rocky escape terrain. (3)

Predators

Gray Wolves (Canis lupus) and Leopards (Panthera pardus) are potential predators. Presumably their influence is not significant because they occur in low numbers or have been extirpated. Harassment and predation by domestic and feral dogs, especially livestock guard dogs, can have a major negative impact on Nubian ibexes, especially females and young. Females with young are expecially at risk of predation. (3)

Food and feeding

In Israel, Nubian Ibexes fed on 40 plant species. Plant species consumed varied seasonally, with an increase in browse during the dry season. Nubian Ibexes frequently feed on 28 plants: 14 shrubs, 9 trees, 4 perennial grasses, and 1 forb species. The 5 principal plant foods are 4 shrubs and 1 prennial grass. During the rainy season, diet changed from browse to perennials, which allowed the shrub and tree species to recover from heavy grazing during the dry period. During a winter of higher than average rainfall. Nubian Ibexes fed exclusively on annual vegetation, avoiding shrubs. In other areas, acacia twigs, and leaves and pods on plants and the ground, are principal food sources. Females have rapid food passage rates, are more selective of forage intake, and more thoroughly masticate forage than males, probably to promote digestion by reducing forage particle size. Males masticate less thoroughly, feed more on fibrous browse, and promote digestion by prolonging exposure of food particles to rumen digestion. (3) Nubian ibex can survive on a very scarce diet. (2) They drink almost daily and are therefore dependent on unhindered access to water. (1)

Breeding

Sexual most active: older males (3)

Mating: occurs in late September and October (3) or October to november (1); in Oman, there appeared to be two mating periods, one in autumn and a second in spring (3)

gestation: 165-175 days (3)

time of births: late March and April (3)

Young per birth: 20-30 % females have twins; triplets have been observed (3)

Males tend individual females and do not form harems

Activity patterns

Daily activity begins at dawn. In hot weather, Nubian ibexes move to north-facing slopes by 8:00 h, where they remain in the shade during the hottest time of the day. They become active again at about 17:00 h. During cold weather, they are active most of the day. In southern Sinai, where lower-elevation areas are occupied by livestock and herders in winter, the ibexes remain at elevations above 2500 m, although daytime temperatures are cold and stressful; they graze in sunlight to absorb solar heat. Females with kids adopt spatial and temporal activity patterns that minimize predation. (3) Nubian ibexes are shy, where they are hunted. In protected areas they can become very tame. During the rut males erect the hair on their backs. (6)

Movements, home range and social organisation

Nubian ibexes have established daily movement routes, moving from nocturnal sleeping sites to areas, where they are active (often wadi beds). During long movements, they avoid lower elevations and instead use trails at higher elevations. Seasonal movements from lower areas in winter to higher areas in spring can occur during the rainy season. Daily movements are about 4-6 km, but vary considerably depending on forage availavility and proximity to cover. During the mating season, adult males can move 5-10 km in one day from one mixed herd to another. Females are less prone to move long distances. Home ranges can be 0,5 km2 or smaller, but some female groups can range over an area of 15 km2.

Nubian ibex social groups consist of:

– mature, mating-age males (6 years of age or more);

– temporary associations of immature males 4-6 years of age;

– female herds that incluce kids and young males up to three years of age (adult females have a dominance hierarchy);

– mixed groups composed of adult females and males and younger males and females including young. (3)

During the non-mating period, females and mature males are in seperate herds. Young males attain the body weight of adult females by age three and separate from female herds by age four. Population densities in a protected area with a population of about 200 ibexes in northern Arabia were 0,26-2,67 ind/km2. The highest densities were in areas more distant from human disturbance. (3) Herd sizes are usually up to 20 individuals but groups numbering more than 100 have been recorded. (1)

Funky biology

47 kids entrapped

Neonatal survival can be highly variable, depending principally on seasonal forage availability. In Israel, annual mortality of young during the first 120 days after birth averaged 37 %. In southern Israel, as many as 47 kids became accidentally entrapped in successive years in a concavity in a steep canyon, because they were unable to scale the precipitous walls until the age of up to 13 days for single kids and up to 20 days for twins. Their mothers returned periodically to nurse the trapped young. (3)

The ibex grooming bird

Nubian ibex have special grooming habits that involve the Tristram’s grackle (Onychognathu tristamii), a member of the starling family. Flocks of these birds tend to the herd, pecking at the hides of the ibex, one grackle per animal. Grackles often compete for a particular individual. (1)

Conservation Status / threats

IUCN classifies the Nubian ibex as vulnerable. It is estimated that there are less than 2500 mature Nubian ibex left in the wild. (5) The Nubian ibex is extinct in Syria and Lebanon and greatly decreased throughout its range and extirpated over wide areas due to illigal hunting, competition with increasing livestock numbers, habitat deterioration and habitat fragmentation due to human settlements, agricultural developments, roads, vehicular traffic, and the associated human disturbance. Establishment of protected areas and travel corridors, with strict enforcement of game laws and limited numbers or complete absence of livestock, is urgent. Protected areas should also be established in areas where ibexes have been extirpated, and populations should be reestablished with wild ibexes from adjacent areas. Monitoring to determine population status, which is conducted in few areas, should be a priority. International management programs between countries that share ibex populations should be initiated. Strictly managed sport-hunting enterprises should be considered; these could provide economic incentives to local communities to maintain and establish wild populations. (3)

From zoo to wild: The San Diego Wild Animal Park sent 22 young ibex to Wadi Mujib Nature Reserve, Jordan in July 1989, to which was added a locally captured juvenile. They reproduced well. In 2006 the program was terminated. The wild population in the reserve was judged stable at about 200 animals. (5)

Trophy hunting Nubian ibex

Sudan: Since January 1992, Nubian Ibex are included as a Schedule II species under the Wildlife Conservation Act. This allows the species to be legally hunted with a special hunting permit. In the 1980ies trophy hunting has once before taken place. For this period it is said that „neither the number of licenses issued, nor the areas open for hunting, were based on any scientific surveys to determine if hunting could be sustained by the populations“. (5) Therefore trophy hunting in Sudan is currently irresponsible. (6)

no trophy hunting any more in:

Jordan: Until 1978, the ibex was legally hunted in Jordan, but since then it has received full protection and a total ban on hunting.

Egypt: The Nubian Ibex is protected by Agricultural Law No. 53/l 966 and amendment 1012 July 1992. Hunting of this species is totally forbidden.

Israel: fully protected; and law is effectively enforced.

Oman: fully protected by law (Ministry of Diwan Affairs, Ministerial Decision No. 4 1976) throughout the country

Saudi Arabia: legally protected by a hunting by-law passed in 1979 which gives the species total protection (5)

There are talks (2010) that Egypt and Oman are contemplating restricted trophy hunting programs for Nubian ibex. (1)

Literature Cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.),1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Alkon, P.U., Harding, L., Jdeidi, T., Masseti, M., Nader, I., de Smet, K., Cuzin, F. & Saltz, D. 2008. Capra nubiana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3796A10084254. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3796A10084254.en. Downloaded on 20 July 2016.

(6) Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern(8)

(7) Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the Pinnacles – Wild Goats of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.