This species from Ethopia, is the most endangered in the genus Capra. [4] It is also the world’s southernmost occurring ibex. The Walia ibex is confined to a very restricted area of about 95 km² in the Simien Mountains of Ethiopia. [1] There is no Walia ibex in captivity anywhere in the world to form a nucleus of a captive-breeding population. [7] It is larger and heavier than the Nubian ibex, with which it is closely related. Infact it is among the largest of the genus. [4] Its coat is dark chocolate to chestnut-brown. Old males have a prominent dark beard. [1] A skeletal peculiarity is a bony process on the forehead. [7] Unlike other Capra species the Walia ibex breeds at all times of the year because of the lack of seasonal changes in the tropics. [1]

Names

English: Walia Ibex, Abyssinian ibex [1]

German: Äthiopischer Steinbock, Walia-Steinbock [2]

French: Bouquetin d‘ Abyssine [1]

Spanish: Capra abesinica, Ibex walie, Íbice de Etiopía [1]

Russian: эфиопский горный козёл

Amharic (an Ethiopian language): Walia [1]

Taxonomy

Capra walie (Rüppell, 1835); Type locality: Ethiopia

In the past the Walia ibex was classified as a subspecies of the Nubian ibex. Genetic data and its unique ecolocical adaptions indicate that the Walia ibex is a distinct species. Molecular genetic data indicate furthermore that Walia and Nubian ibex have had a seperate distribution for a long time. They form a monophyletic clade seperate from an ancestral central Asian ibex. [3] In general, the Walia ibex may be viewed as a hypermorphic derivative of the Nubian ibex: that is, a logical prolongation of the growth-process of the latter. [4]

Distribution / countries occurence

Northern Ethiopia, Simien Mountains National Park, 25 kilometers along the northern escarpment. Small numbers occur outside the park. [3]

General discription

total length: head-body 175-196 cm (males) [3]

shoulder height: 75-110 cm (males); 65-100 (females) [3]

tail length: 22,5-25 cm (males) [3]

beard: prominent and dark [3]

weight: 100-125 kg (males) [3]

horn length: 89-114 cm (males) [3]

life span: rarely more than 11 years (males) [3]

In terms of coloration there is some resemblance with the Spanish ibex. But Walia ibex are closely related to Nubian ibex. Both have an ancestor in central Asia. Photo: Christof Asbach

Coloration

General body color is chestnut brown. Chin, throat, underside of the body, and inner surfaces of the legs are whitish, with a black stripe extending down the front of each limb. White bands above the knees and hooves cut across the black stripe of the front and hindlegs. Males seven years and older have a prominent dark beard, and dark chest and flank stripes that connect with the dark upper front legs and dark upper front surface of the hindlegs. Females and young males lack beards. Males have a black mid-dorsal stripe that extends to the tail. The whitish rump patch is small, confined to the anal area, and mostly covered by the relatively long tail. [3]

Horns

Horns are flattened laterally (which means they are broader when looking from the sides), they diverge slightly and grow upward in a scimitar-shaped curve. [3] The horns are more massive than those of the Nubian ibex, but not quite as long. [1] The horn cores are more expanded. [4] The horn tips are always pointing inward. [6]

Habitat

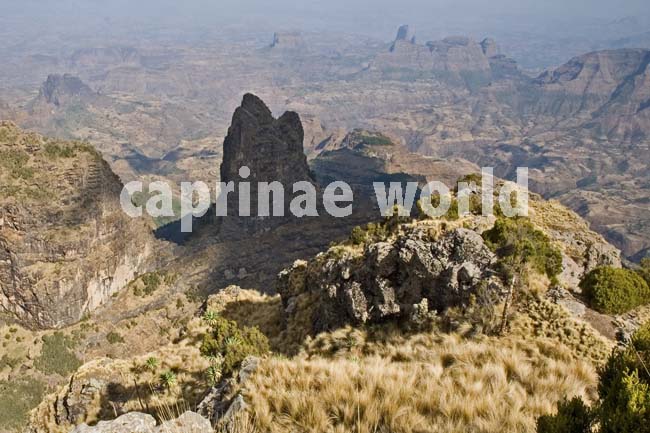

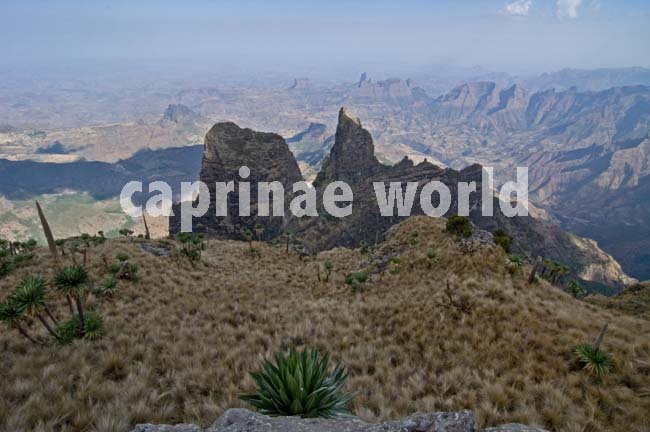

Walia ibex occur at an average elevation of 3390 m (range: 2500-4200 m) in forested areas, tall shrub habitats, and also tall grass meadows and savannas. Their habitats are characterized by heterogeneous slopes including escarpernts, deep canyons, and other rocky habitats. 30% of sightings of Walia ibexes were on 30-40° slopes and 64% on slopes greater than 45°. Females are associated with steeper terrain than males. Walia ibexes prefer east-facing slopes, which receive more rain than west-facing slopes. Resting animals prefer ridges that overlook large areas and afford security. [3] Compared to the Nubian ibex the Walia ibex selects high altitudes in relatively wet environments with extreme day/night temperature differences and colder average temperatures. [1]

Walia ibex habitat: Among other things they feed on Giant Lobelia (the green plant in the picture). Photo: Christof Asbach

Food and feeding

Browse is the magor diet component. They rise up on their hind legs to reach the tender shoots of tree heath (Erica arborea) and Giant Lobelia (Lobelia rhynchopetalum). [1] Grasses may comprise 11% of the diet. [3] Furthermore they feed on herbs, creepers and lichens. [1] Walia ibexes feed on slopes or terraces near steep, rugged terrain. [3] Walia ibex do not tend to drink; it is assumed they get sufficient moisture from their forage. [1]

Breeding

sexual most active: males at least seven years old do probably most of the mating [3]

mating: throughout year, with a peak in March-May [3] or March and June [1]

gestation: 165-175 days [3]

time of births: there is a birth peak in September-October, toward the end of the rainy season [3]

young per birth: twins are probably rare [3]

Movements, home range and social organisation

Walia ibexes usually do not have seasonal movements. Males probably have larger home ranges than females. Males and females are not completely segregated at any time of the year, probably because there are females in estrus throughout the year. 40% of ibex herds containeed males and females of all ages; 84% of the animals were in mixed herds, indicating that males join female herds during all seasons. Males at the age of two to three years join older male herds. [3]

Conservation Status / threats

The IUCN Red list classifies the Walia ibex as „endangered“. [7] In 1968/69 the population level was estimated to be around 200 to 250. Protection measures were introduced in the 1980s. In 2010 the population numbers was put around 740 [1]. Excessive numbers of livestock are causing habitat degradation and disturbance. The increasing human population in scatttered settlements within and outside the park and ensuing agricultural development in steep terrain are further degrading habitats. Cutting of trees and shrubs for firewood and human-induced forest fires add to the continuing habitat degradation and destruction. [3]

The creation of strictly managed game ranching enterprises outside the park, including sport hunting, could promote incentive-driven, community-based conservation initiatives, encourage the protection of ibexes outside the park and make it possible to establish populations in other areas. [3]

The Ethiopian national soccer team calls itself „The Walias“. The use of symbols can help to win sympathies for the species.

The Walia ibex is used by the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Organisation (EWCO) and the Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society (EWNHS) as their emblem, and frequently features in other Ethiopian symbolism, such as the national football team. [7]

Trophy Hunting

Walia ibex have been fully protected in Ethiopia for over 120 years. All legal hunting ever since was based on individual permits granted by imperial edict. The last legal hunt for walia took place in 1968. [1] It can be hunted under a „special permit for hunting game animals for scientific purposes“. [7]

Literature Cited

[1] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

[2] Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.),1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

[3] Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

[5] Geberemedhin, B. & Grubb, P. 2008. Capra walie. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3797A10089871. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3797A10089871.en. Downloaded on 10 May 2016.

[6] Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern(8)

[7] Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the Pinnacles – Wild Goats of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.