In wild sheep and goats horns are often the most striking features. The following nomenclature can help to look closely at them, weather you want to identify species or get some hints to the life history of the animal.

general remarks

horn material: Horns are composed of keratinized epidermis (as in fingernails or hooves) while antlers (deer) are composed of bone. [1]

Fallow deer bleeding while shedding off velvet. Antlers grow and are shed off annually. Once the growth is finished, the velvet bursts and is stripped off. The material underneath the velvet is pure bone. The blood, when it is dried, gives the antlers their distinct color. Photo taken at: Tierpark Lange Erlen, Switzerland

According to Geist, horns are environmentally sensitive „luxury“ organs, where size and shape reflect the quality and quantity of forage as well as climatic influences. They are organs of low growth priority that get their share of the body’s recources only after parts of the body have had theirs. Only the horns of very well developed, mature individuals are therefore useful in comparisons, since here the nutritional effect is minimal (Geist 1989, CIC Symposium on Wild Sheep, Prague) [9]

horn growth: The horns of caprini species grow throughout the life of the animal and unlike antlers, are not shed annually. [1,2,3] So horn length increases steadily with age, with the result that the longest and heaviest horns are generally carried by the oldest animals. However, horn growth is affected by several factors, and the largest horned individual is not always the oldest. [6] Ultimate horn length is a function of inheritance and nutritional factors. [1]

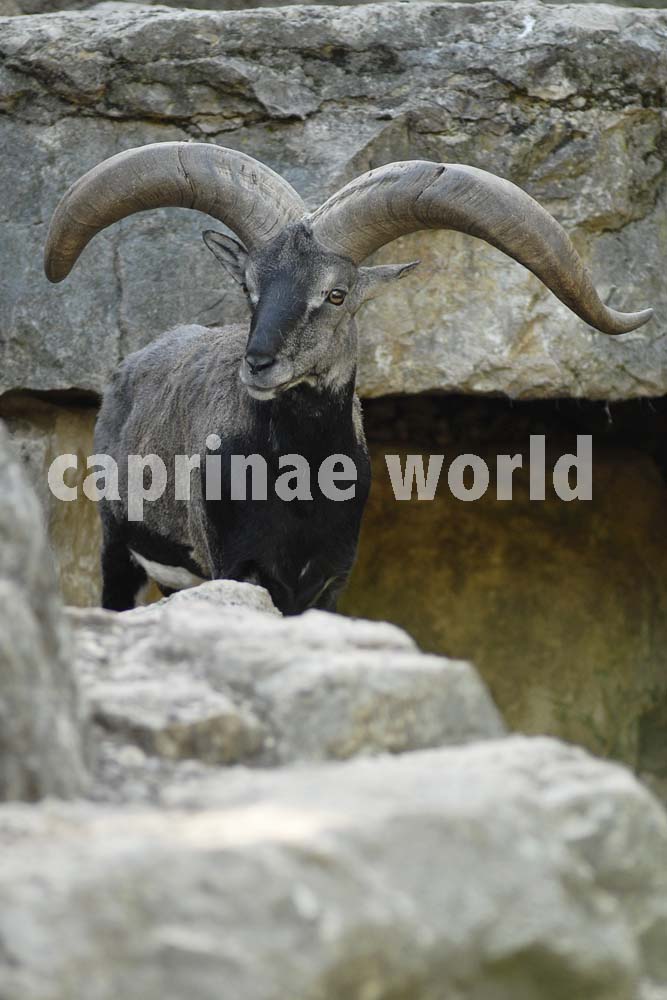

15 year old Asiatic ibex. Note the weathered appearance of the horns. Photo taken at: Wuppertal Zoo, Germany

Horns do not regenerate if brocken and are never branched. [3]

Iberian ibex. Note: In this specimen after the seventh year the horn increments become notably smaller. Photo: Petra Wiedemann at Gredos, Spain

brooming: The loss of horn substance at the tips; is due principally to splintering during clashes and attrition due to rubbing on objects. Brooming is characteristic to tight-curled forms. Probably these forms are more likely to damage tips during clashes. In the New World it is most common in Rocky Mountain and desert bighorn while in the Old World forms it is most evident in the Tibetan argali although all sheep exhibit it to some degree. [1]

Bighorn ram with broomed horn tip. Note the spruce twig at the end. Photo taken at: Maligne Canyon, Jasper Nationalpark, Canada.

Hornforms

nomenclature of horn surfaces and edges: can be important in distinguishing some subspecies, particularly in moufloniforms and argaliforms. [1]

Young Marco Polo argali. Discriptions taken over from Valdez, 1982. Photo taken at: Berlin Tierpark.

anteroposteriorly arched horns. meaning arching from the front (forehead) to the back. Example (serows)

vertically falciform (sickle-shaped) horns. Examples: ibexes, bezoar goat, West Caucasian tur

vertically spiralling horns: markhors and most Spanish ibex

Iberian ibex: The spiral in this species is much wider compared to the markhor. Photo taken at: El Torcal, Spain

cervical horns: grow towards the neck; example: Esfahan mouflon [1]

supracervical horns: curve above and behind the neck; example: Armenian mouflon [1], east Caucasian tur [2].

Armenian Mouflon. Note, how the horn tips are almost merging behind the neck. Photo taken at: Tallinn Zoo, Estland.

homonymous horns: the right horn grows in a right-handed spiral and the left one in a left-handed spiral; example: most sheep [1]

Left horn of a Tibet argali. To comprehend the direction of growth in horns, one has to consider two things: 1. When talking about „left“ or „right“, you should look at it from the point of view of the animal. 2. When following the direction of growth from the base of this left-sided horn to the tip, one must use the index from the left hand and follow the arrows. Then you get a left handed spiral on a left-sided horn – aka „homonymous horn growth“. Do not use your index finger from your right hand and follow the direction of growth (arrows) of this left-sided horn. If you did that, you would get a right-handed spiral – which is not, what was originally intended. Photo taken at: Beijing Zoo, China

heteronymous horns: the right horn grows in a left-handed spiral and the left horn in a right-handed spiral; example: wild goats, markhor and Spanish ibex [2]

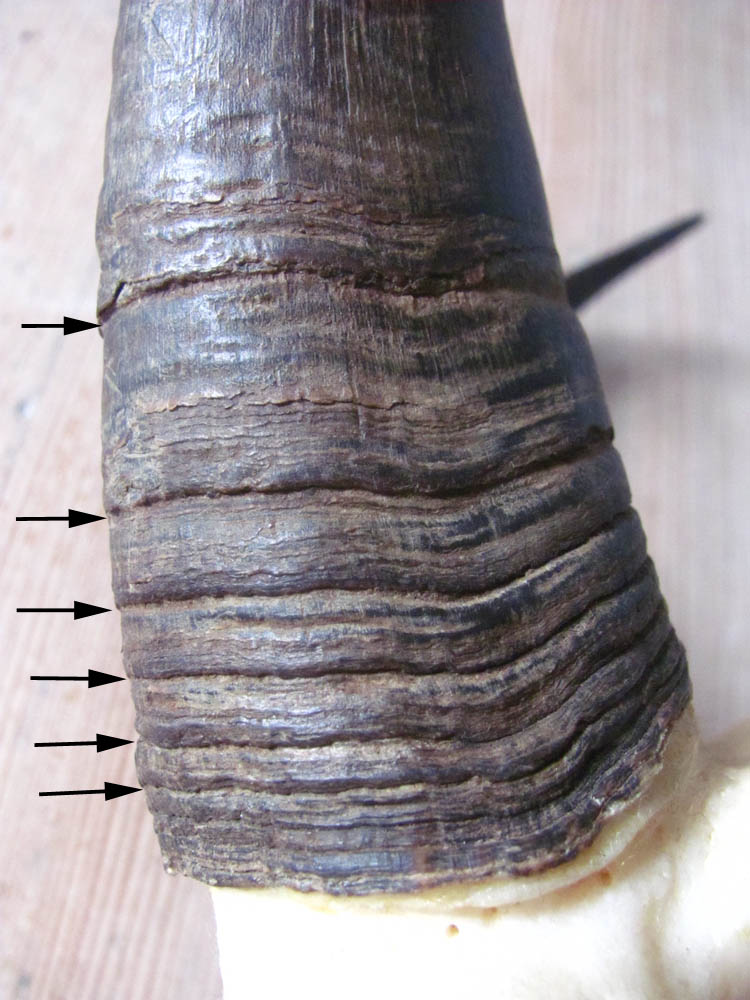

growth ring, annulus or „annual groove“: annuli are circular lines alongside the longitudinal axes of horns; they originate each winter; therefore they can be used to determine age [1, 8] Meile et al. (2003) talk of „Jahresfurchen“ – best translated as „annual grooves“. [8] This term refers to the genesis of the „ring“, which corresponds actually to the cessation of annual horn growth.

Chamois horn with annual grooves

In bezoar goats, each annulus is usually associated with a prominent excrescence which develops on the keel, whereas in ibexes the annulus develops between the bosses. [2]

Alpine ibex. Ibexes usually build two knobs per year. Note that this specimen had one year with three knobs. Photo taken at: Augstmatthorn, Switzerland

Caution should be exercised not to count false annuli. They particularly occur in desert forms perhaps due to the unreliable seasonality of forage whose growth is dependent on irregular rainfall. In some cases the first and even second year’s growth may be absent. (1, 8)

Nubian ibex. Note that several annuli are rather inconspicuous. Photo taken at: Al Ain Zoo by Wolfgang Dreier

boss or knob: horizontal structures that develop on the front horn surfaces of ibex species and the West Caucasian tur. [2] With age knobs can wear off.

keel: keels are sharp longitudinal ridges that can be found on horns – but depending on the species in different ways: Markhors have them on the front and back of the horn, bezoar goat develop them on the front and Spanish ibex show a weak anterior keel and a sharp posterior keel. [2]

combat edge: protrusion on the front side of horns; in old Karatau argali rams and Bighorn sheep [5]

Bighorn ram. Note the area, where the combat edges are located (right horn marked with white triangle). Photo taken at: Jasper National Park, Canada

Species specific discriptions of horns

Note that morphological descriptions for species are generalizations or statistical approximations. In real life there is a lot of variation in horn forms within each species – due to age, sex, health, habitat quality, constitution etc. of each individual.

horns short, simple, conical, dark, back-curved, sharply pointed: (3,6) mountain goat, gorals, serows

horns broad at base, sometimes hardly ringed: goral [5]

Male Red goral. The loss of rings in this specimen is certainly due to rubbing on hard objects. Photo taken at: Beijing Zoo

horns narrowing gradually and evenly along their length, closely ribbed with flat rings to more than halfway along: serow [5]

horns vertically rising, with backward hooking tips: chamois species [3, 6]

horns to the sides, down and outward curving; joining on the forehead in a broad boss: muskox [3, 6]

broad-fronted horns [3]: Bharal (Blue sheep), ibexes

Very impressive bharal. Note that there is hardly any space left between the horns. But „broad-fronted“ actually refers to a broad front instead of a horn front with a keel. Photo taken at: Mulhouse Zoo, France

narrow-fronted horns with sharp keel running up front surface; scimitar-shaped: [3, 6] wild goat (bezoar) – for photo see above

scimitar-shaped horns with relatively flat surface; broken by prominent transvers ridges: ibexes [6] – for photo see above

„beveled-off form“ in ibex species – horns with anteroexternal corner (outer edge of horn – facing the animal) rounded: alpine ibex [5]

Alpine ibex. Photo taken at: Augstmatthorn, Switzerland

„squared-off form“ in ibex species: horns with the anteroexternal angle as well developed as the anterointernal angle – Nubian ibex, Walia ibex, Asiatic ibex [5]

Nubian ibex. Note the difference between these horns and the ones of the Alpine ibex above. Seen from the front the horns appear to be rectangular. Photo taken at: Al Ain Zoo

horns with slight dorsal keel: Walia ibex [6]

Walia ibex from Ethiopia. Arrow indicates a stretch of the dorsal keel. Photo taken in the Simien Mountains by: Christof Asbach

thick-based horns in Capra species: [5] Kuban Tur and Daghestan Tur

laterally flattened horns with prominent keel in front: [6] Himalayan tahr, Arabian tahr

Arabian tahr. Note that the keel is actually accentuated through a depression line along the base of the keel. Photo taken at: Sharjah breeding center, United Arab Emirates by Wolfgang Dreier

front of horns „almost flat“ [6]; horns transversely wrinkled – the inner surface nearly flat, the outer surface highly convex: [5]; Nilgiri Tahr

Nilgiri tahr. These horns differ a lot from the other tahr species. Photo taken in Kerala, India by Sankara Subramanian

heavy, corrugated horns sweeping out, back and in again: Aoudad [6]

laterally pointing horns from swollen bases [3]; curve up, out and back [6] and up again: Takin

mediolaterally compressed horns: [5] Chiru; as if the horns were pressed together between the ears

horns in one plane: Bukhara urial [5]

Bukhara Urial. The „in one plane“ is not to be taken literally. But you get the idea. Photo taken at: Tallinn Zoo

crenellated horns: Gobi Argali [5]

horn surface strongly wrinkled: Altai Argali [5]

This impressive specimen is actually an Altai-Argali 0,1 x Kamtchatka Snow sheep 1,0-Hybrid. Nevertheless the wrinkled horn surface is remarkable. Photo taken at: Novosibirsk zoo

terminal part of the horns twisted outward: Marco Polo sheep [5]

frontal sinuses with complex septa [3]: air-filled spaces in horns that originate from the nasal cavity, located wholly within the vaulted (expanded) frontal bone; function to some degree as shock absorbers, protecting the brain from blows during intraspecific combat. [4] In Sheep, Himalaya-Tahr, Aoudad and Bharal the sinuses are extended throughout the frontals, with complex septa, but much less so in Capra. [5]

What are horns used for?

- impressing: male alpine ibex are thought to impress other members of their herd by just presenting the horns. [8]

Two Alpine ibex. The right specimen is presenting, while the left animal shows a threatening posture. Photo taken at: Benediktenwand, Germany.

- threatening: horns are used to signal readiness to engage in more serious interactions: horns are tilted toward an oponent or in the medial horn presentation the neck is held about shoulder level, horns pointing upward.[3]

Two mountain goats. Note: the animal in the back arches, while the animal in front lowers its body. Photo taken at: in Jasper Nationalpark, Canada

- pacification: males of various caprinae species put their heads back while approaching females during mating season as if they wanted to hide their dangerous weapons. [8]

- sparring: playful fighting; the background for sparring could be high spirits, excercise or testing the opponent.

- ramming: head clashing; may be the most dramatic fighting technique of all and perhaps most emblematic. Particularly goats, ibexes and sheep vying for dominance and breeding rights perform ramming; seen also in bharal. [3]

Alpine ibex. The fight that was documented here actually last four hours. Photo taken at: Benediktenwand, Germany

- butting: bashing head and horns on other parts of the body: seen in goats, sheep Markhor [3] and ibex

Kuban tur. Sometimes it’s hard to tell if it is bashing or cuddling. Photo taken at: Tallinn Zoo, Estland.

- parallel fighting: [3] a less serious form of sparring that involves standing side by side or at an angle, and with the horns interlocked, neck-wrestling or pushing sideways. For example: Aoudads

- „horn sweeping“ and „horning the ground or vegetation“: nearly universal among bovids. These behaviours are not always directed at another individual, but they communicate prowess if conspecifics are looking on. They also may be used outside of the breeeding season to establish male social rank or issue a warning. [3, 8] In chamois it is believed that horning is first and foremost a means for wellbeing. [7]

Mountain goat. This sweeping of vegetation was a clear sign to the photographer that he had come too close. Photo taken at Avalanche valley, Montana, USA

- defending predators: For example muskoxen will form a circle around offspring and aggressivly defend them from predators such as Gray Wolves; horns on the females confer an obvious advantage under such circumstances. [3] Alpine ibex have been seen to force back attacking golden eagles [8; personal observation]

- scratching:

This Alpine ibex uses one of its horns to scratch its flank. Photo taken at: Benediktenwand, Germany

This Alpine ibex has left a clear sign that female ibexes with their shorter horns are also capable of scratching their bodies. Photo taken at: Benediktenwand, Germany.

- cuddling:

A young male Alpine ibex welcomes a newborn, just a few minutes old. Photo taken at: Tierpark Peter&Paul, St. Gallen, Switzerland

- ground slinging: aoudads and mountain goats use their horns to sling soil or sand at themselves. This behaviour is probably part of wallowing (i.e. lie down and roll over; for example to cool off).

- „tool“ use: chamois have been observed having helped their newborns to stand up using their horns. [7] Male alpine ibex sometimes lean back while resting or sleeping, using their horns as supports. [8]

Literature cited

[1] Valdez, Raul, 1982: The wild sheep of the world. Wild sheep and goat international.

[2] Valdez, Raul, 1985: Lords of the pinnacles – wild goats of the world. Wild sheep and goat international.

[3] Wilson, D.E and Mittermeier, R.A. (eds), 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

[4] Farke, Andrew A., 2008: Frontal sinuses and head-butting in goats: a finite element analysis. Journal of Experimental Biology 2008 211: 3085-3094. http://jeb.biologists.org/content/211/19/3085

[5] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate taxonomy. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

[6] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain monarchs. The University of Chicago Press.

[7] Schnidrig-Petrig, Reinhard and Salm, Urs Peter, 2009: Die Gemse. Salm Verlag, Bern.

[8] Meile, Peter; Giacometti, Marco and Ratti, Peider, 2003: Der Steinbock – Biologie und Jagd. Salm Verlag 2003, Bern

[9] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa