The Alpine ibex lives in the mountains of the European Alps. It’s conservation success story is unsurpassed.The Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) is the least colorful of the Capra species. Males have a relatively short beard. It can also be distinguished from other ibexes by its horns which have rounded anteroexteral corners.

In the 19th century Alpine ibex were almost extirpated. Today the conservation status of the species is considered to be of „least concern“ by the IUCN. Therefore the Alpine ibex stands for one of the great success stories in wildlife conservation. Legal hunting today does not threat the species.

German: Alpen-Steinbock; French: Bouquetin des Alpes; Spanish: Íbice de los Alpes; Russian: альпийский козёл; Italien: Stambecco; Slovenian: kozorog

Taxonomy

Capra ibex Linnaeus, 1758; Type locality: Switzerland, Valais.

Distribution

Switzerland, S Germany, Liechtenstein, Austria, N Italy and SE France, NW Slovenia. Introduced outside the Alps: Rila mountains/Bulgaria(4), Swiss Jura/Creux du Van(5)

General

head-body: 115-135 cm (males); 55-100 cm (females) – medium sized species

shoulder height: 65-95 cm

tail length: 21-29 cm (males); 15-23 cm (females)

beard length (only males): short, 7 cm

weight: 70-120 kg (males); 40-50 cm (females)

horn length: 85-95 cm (males); up to 35 cm (females)

Life span: 22 years (in capitivity); in the wild 16 years (males), 19 years (females)

Diploid chromosome number: 60

Body

Males reach maximum body size at 8,5-10,5 years and females at 4,5-5,5 years. Females can weigh 50% less than males. Males may loose 20% of body weight in winter. (2)

Coloration

The Alpine ibex is the least colorful of the ibex species(7). In winter, older males are dark chestnut brown with white belly; sides of body, lower chest, and legs are dark; tail is black and bushy. White, narrow rump patch is restricted to area about the length and width of the tail. Females are uniformly brown but with a black tail and dark stripe along lower portion of body. Miscellaneous: Calluses develop on the carpal joint of front legs. In summer, males and females are yellowish-brown but males have paler neck, forehead, and flanks.(2)

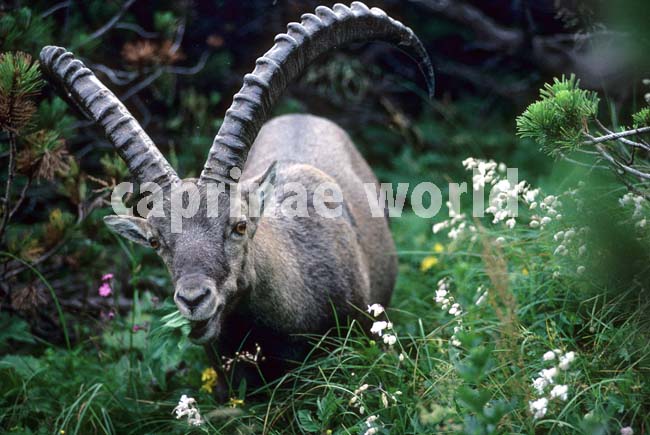

Horns

Male horns grow upward and diverge in a scimitar shape. Species characterized by the anteroexteral corner of the horns rounded.(1) Horn growth is greatest during the second year, with significant individual heterogeneity in horn growth. Individuals with the longest horn growth as young adults also have the longest horns later in life; longe horn length in adult males is indicative of genetic quality.(2)

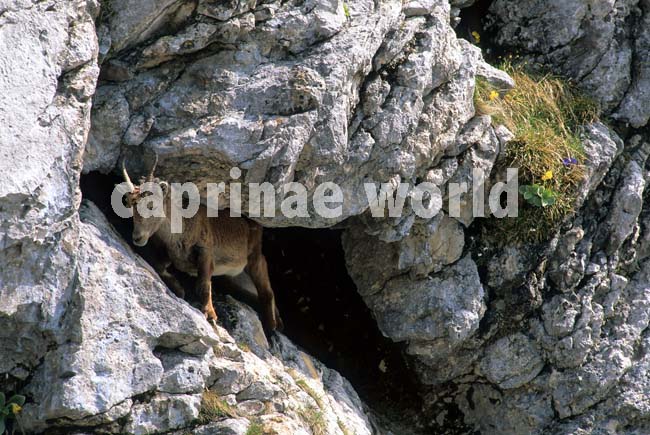

Habitat

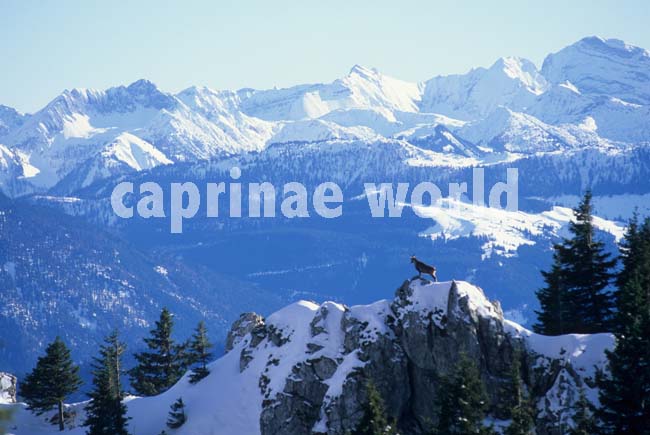

Alpine and subalpine habitats at elevations of 500-3200 m (2;4); can also use open forests in rocky terrain associated with ledges, cliffs, and precipitous valleys. In winter Alpine ibexes use precipitous slopes (30-45°) with minimal snow cover. Overhanging ledges and caves provide thermal cover.(2)

Alpine ibex usually chose steep, south- and southwest facing slopes during the winter to avoid deep snow cover. But during mating season males wander through unfavorable habitat to reach female groups. Photo taken at: Benediktenwand, Germany

Food and feeding

Annual diets consist of about 60% grasses, 38% forbs, and 2% browse. Consumption of browse increases in winter and spring.(2)

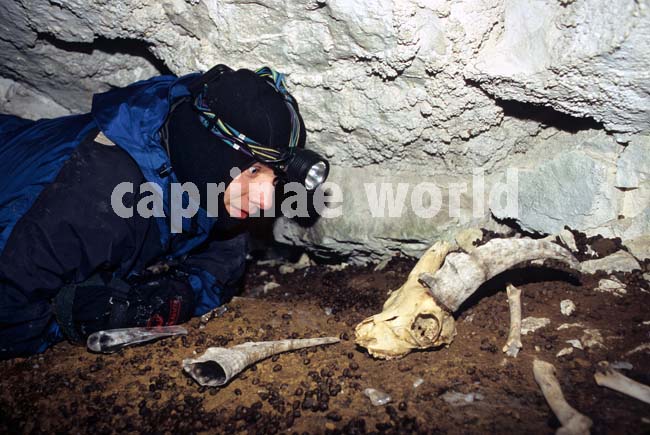

Greatest mortality factors

old age, starvation, disease (e.g. infectious keratoconjunctivitis, resulting in blindness – can result in 30% mortality), avalanches (2)

Predation

negligible because of absence or scarcity of large predators(2); otherwise red fox, wolf, golden eagle for kids

Breeding

Sexual Maturity: 1.5 years, female’s first precnancy can be delayed until 3-4 years of age or later in high-density and poorly nourished populations.

Mating: December-January

Gestation Period: 165-175 days

Parturition: June

Young per birth: 1, rarely 2

Activity pattern

Grazing of this diurnal species occurs primarily during the morning and late afternoon (4). On average, males spend 51% of their daily activity budget grazing, 38% resting, 4,8% standing, 2,4% moving, and 3,8% in other activities. Ibexes move to higher elevations and nearly stop feeding during hot and sunny days, and remain at lower elevations and feed at all hours during cooler and cloudy days. In a study heavier males moved higher copared to smaller males, given the same increase in air temperature. Small males spent more time feeding than large males. Males also spent more time lying, standing, and walking than females. Males of all ages spend less time foraging during the rut than before or after the rut.(2)

Movements, home range and social organisation

During the winter, Alpine ibexes may move to lower-elevation, snow-free areas. In winter they also prefer south- and south-west-facing slopes that are steep and snow free.

During spring they follow the retreating snow line upward, feeding on fresh plants, they remain at higher elevations from July to October. There is usually overlap between winter and summer ranges. Female with young use habitats in or close to precipitous, rocky terrain. Males are not so much dependent on steep slopes. They move greater distances than females, seek out alpine meadows, and make more frequent use of areas disturbed by humans, such as roads, villages, and hiking trais, which are charaterized by higher forage quality.

Snow cover can restrict home range size. Home ranges are larger in summer and autumn, smaller in spring, and smallest in winter; the ranges of males are larger than those of females. Home ranges of recently translocated populations can be several times larger than those of established populations.

Males and females are spatially segregated from spring to autumn. Males join females during the mating season. Males associate with other males of similar age and social status. Adolescent males remain with females until about age three, when they join male herds.(2)

Conservation Status

IUCN Red List: least concern. The Alpine ibex was on the verge of extinction in the 1800s, just one protected population remained – less than 100 animals (7) – in northern Italy (today: Gran Paradiso National Park) and the neighbouring French valley of Maurienne (today: Vanoise National Park). This area is the source from which reestablished populations in the Alps originated.(2) The introduced populations of ibex appear to have low genetic diversity(3). Nevertheless this has so far not been an obstacle in succesfully establishing populations. Number of mature individuals today: 31420.(4) Alpine ibex are one of the great stories of wildlife conservation.(1)

Hunting is allowed in managed populations in Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein, Bulgaria and Slovenia.(2;4) Legal hunting is well-managed and is not considered a threat to the species.(4)

Traditionally Alpine ibex were also hunted for body parts like this bezoar, which can be found in the stomach of ibexes.

The bezoar was used in traditional medicine. Bezoars were believed to have the power of a universal antidote against any poison.

Literature Cited

(1) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(2) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(3) Biebach, I.; Keller, L. F., 2009: „A strong genetic footprint of the re-introduction history of Alpine ibex (Capra ibex ibex)“. Molecular Ecology 18 (24): 5046–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04420.x

(4) Aulagnier, S., Kranz, A., Lovari, S., Jdeidi, T., Masseti, M., Nader, I., de Smet, K. & Cuzin, F. 2008. Capra ibex. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T42397A10695445. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T42397A10695445.en. Downloaded on 12 April 2016.

(5) Weissbrodt, Michel, 2003: Le Bouquetins du Creux du Van. Les Editions du Château, Colombier NE.

(6) Irène Girard, 2000: Expansion of the European Ibex (Caprex ibex ibex, L.) in the Alps. Thesis, Université de Savoie.

(7) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.