Desert Bighorn Sheep are distributed in the United States and Mexico. Rams often give the impression of having disproportionately large horns.

Names

English: Desert Bighorn Sheep [2, 4] aka Desert Sheep [2]

French: Mouflon Bighorn du désert [2]

German: Wüsten-Dickhornschaf [2]

Spanish: Borrego cimarrón [2]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms [2]

Ovis montana, Baird & Scott 1859

Ovis nelsoni, Merriam 1897

Ovis mexicanus, Merriam 1901

Ovis cervina cremnobates, Eliot 1903

Ovis canadensis gaillardi, Mearns 1907

Ovis canadensis texiana, Bailey 1912

Ovis canadensis sheldoni, Merriam 1916

Ovis canadensis weemsi, Goldmann 1937

Taxonomy

Ovis canadensis nelsoni Merriam, 1897 [2]

diploid chromosome number: 54 [2]

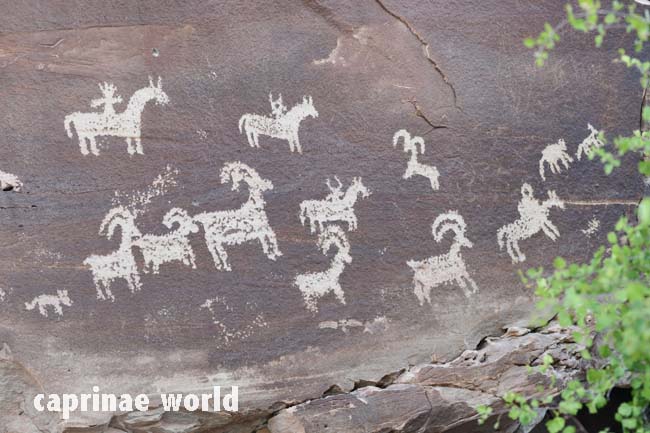

Older descriptions (compare Toweill and Geist 1999) considered Desert Bighorns to be relict populations and holdouts from the time when glaciation in North America forced ancestral populations southwards. According to this hypothesis, they became stranded in isolated mountain ranges gradually adapting to a drier habitat after the retreat of the glaciers. [2]

As new genetic and morphometrical data emerged, Cowan’s taxonomy of Ovis canadensis was modified, starting in 1965 with Baker and Bradely and reinforced in 1993 by Ramey and Wehausen. Molecular dating proves that Desert Bighorn Sheep and Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep diverged 300-400 thousand years ago. There have been 3 to 4 glacial and interglacial cycles since separation, thus refuting the old relict idea. As a group, Desert Bighorns are a recent radiation, which is also why there are no valid Desert Bighorn subspecies. [2]

Subspecies

As a result of morphometrical measurements, protein and mtDNA analysis, Ramey (1991, 1993, 1995) recommended that of the four subspecies of Desert Bighorn Sheep, only a single subspecies – Ovis canadensis nelsoni – be recognized. [2]

Table 1: Desert Bighorn Sheep subspecies – current and former

|

Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni)

|

Mexican Bighorn (O. c. mexicana) Peninsular Bighorn (O. c. cremnobates) Nelson’s Bighorn (O. c. nelsoni) Weems‘ Bighorn (O. c. weemsi) |

Distinctions between other Bighorn subspecies: Geist (1971) noted that more southerly populations from lower altitudes and poorer forage may be expected to be smaller than the more northerly, high altitude and cold adapted populations living in seasonally abundant forage habitats. In fact Desert Bighorns are smaller than Rocky Mountain Bighorns, but similar to Sierra Nevada Bighorns. [2] Desert Bighorns have short hair and longer ears, while northerly Bighorns have long awn hairs and a dense undercoat and small, thick-haired ears. [5]

Distribution

by country: United States (West), Mexico (North) [6]

In the United States, Desert Bighorn (O. c. nelsoni) inhabit southern portions of California, Nevada, Utah and New Mexico, much of Arizona, and west Texas. Weaver (1985) estimated 16.000 Desert Bighorn in this area. However, there are few Bighorn and few herds (mostly transplants to reintroduce Bighorns in areas where they were extirpated) within the Chihuahuan Desert of New Mexico and west Texas. [6]

In the United States the historical distribution range of the Desert Bighorn Sheep stretched far enough north to include all of Oregon, northeastern California and southeastern Idaho. In all these regions, as well as in northwestern Nevada, the original O. c. nelsoni populations were extirpated. Introductions during the 20th century replaced the original Bighorns [2]

In Mexico, the Desert Bighorn is distributed in the northern states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Sonora, and most of Baja California. [2]

Description

general appearance: Bighorn Sheep – in general – are blocky animals with compact bodies, relatively short legs, muscular front and hindquarters, sturdy necks and backs.

Young ram: Desert Bighorns – compared to Rocky Mountain Bighorn – have a more slender build. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

shoulder height: 83-97 cm [2]

weight males: mid 60 kg and normally not exceeding 100 kg [2]; up to 104 kg [7]

weight females: 35-60 kg; but apparently DeForge has weighed ewes in Baja California at 81 kg, which puts them up with Rocky Mountain Bighorns [2]

scull: short and broad [2]

molar teeth: heavier than in Rocky Mountain Bighorns [2]

average scull weights: Desert Bighorn 7,5 kg – compared to 11,3 kg in Rocky Mountain Bighorn [10]

ears: longer than in Rocky Mountain Bighorns [2]

Desert Bighorn females. Note the big ears. Specimen in the back has its right horn broken. Photo: Ralf Bürglin / Plzeň, 2018-04

Colouration / pelage

pelage in general: paler; vary in colouration from a light buff to a chocolate brown, with a deeper reddish tinge on the neck and shoulders, and a more greyish tinge on the underparts [2]. In general animals from southern populations are lighter than those of more northerly areas [7]; but Wehausen (2011, pers. comm.) states that sheep from Baja California may show a darker, to very dark, pelage contrasting with the pale brown found in Desert Sheep farther north. [2]

muzzle: almost white [2]

eyes: with light-coloured rings [2]

legs: with white edging on the rear legs [2]

tail: black; bordered in white [2]

rump patch: small, white; a dark line divides the rump patch lengthwise to the base of the tail [2]

underparts: more greyish [2], instead of white as in Rocky Mountain Bighorns

Horns

Desert Bighorn rams often give the impression of having disproportionately large horns relative to body size. Corrugations are not pronounced. Horn colour varies, depending on locality, from light reddish-yellow to dark reddish-brown. [2]

Desert Bighorn rams often give the impression of having disproportionately large horns relative to body size. Photo: Gregory Smith, Zion-NP, Utah.

Desert Bighorn Sheep scull: displayed at Canyonlands National Park visitor center. Both ends are broomed. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

horn length, males: 91 – 107 cm [2]

horn length, females (from Arizona): 25,4 – 33 cm [2]

base circumference, males: 36 – 43 cm [2]

horn circumference, females (from Arizona): 7,6 – 15,4 cm [2]

Horns of Desert Bighorn ewes seem to be larger on average than those of ewes from the Northern Rocky Mountain subspecies. Cowan’s (1940) statement that ewe horns of the putative Peninsular race represent the largest in the species canadensis was however, refuted by Wehausen and Remey (1993). [2]

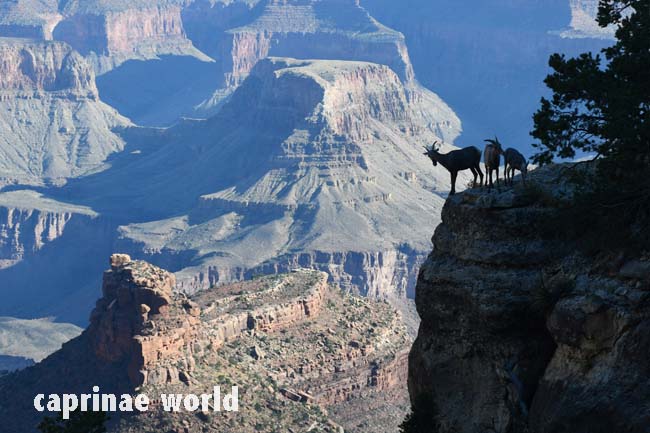

Habitat

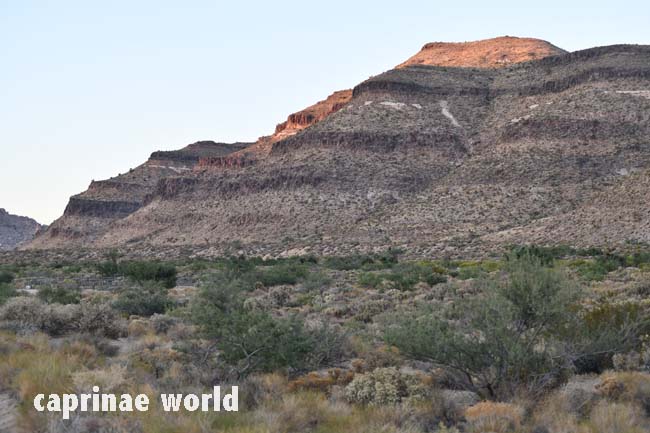

Desert Bighorn Sheep inhabit arid, naturally fragmented environments of isolated mountain ranges with unpredictable rainfall between sea level to 4.343 m asl (White Mountains, California). Climatic conditions are diverse, from those with cold winters and hot summers, to those with mild winters and hot summers or those with warm temperatures year round (Baja California) [2]. In the desert habitats temperatures can be greater than 40°C. [16]

Food and feeding

Bighorns in general mostly eat grass, but they also consume forbs and browse. [6] In desert areas, shrubs can comprise more than 90 per cent of summer diets. [16] For example Desert Bighorns feed heavily on jojoba (Simmondsia chinensis). Pincushion, barrel and cactuses provide moisture. The plant species eaten vary greatly between seasons, even years and in different desert habitats. [2]

Water and seasonal precipitation have important effects on forage availability, quality, and palatability, especially in desert environments, and largely determine diet composition. [16] Desert Bighorns drink every 3 to 5 days on the average if available (Welles and Welles 1961). [10] But sheep can survive without standing water for long periods [16].

Predators

Major predators of Desert Bighorn Sheep are Pumas (Puma concolor) [2, 16], and furthermore Coyotes (Canis latrans) and Bobcats (Lynx rufus). [16] Golden Eagles have been observed taking lambs. [2]

Breeding

sexual maturity: at 18 month [2]

rutting season: in northern Bighorn populations in late November and early December; in desert environments, mating season is prolonged [16]

gestation period: almost 6 months [2]

lambing season: in desert environments births occur from January through June, probably due to unpredictable precipitation patterns, although there is usually a peak period in births. [16]

parturition timing: In desert environments the peak birth period coincides with a predictable timing of the winter-spring forage growing season, indicating that most Desert Sheep births also coincide with the period of nutrient availability [16]

number of young: one, very occasionally twins [2]

Activity pattern

Feeding periods increase, probably influenced by the poorer nutritional quality and availability of forage plants, especially in deserts. Feeding activity is curtailed by high summer temperature during the day. [16]

Under better habitat conditions Desert Bighorn have more time to rest. Photo: Gregory Smith, Zion-NP, Utah

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

Desert population movements are related to seasonal water and forage availability. Males tend to make longer movements and have much larger home ranges than females, especially during the mating season. They can move 50 to 60 kilometres and encompass several mountain ranges. In the pre-Columbian period, when human structures were not a hindrance, desert populations were not sedentary, and the sheep crossed lower-elevation intermountain regions to move between mountain ranges. [16]

Sex, water, forage: decisive for home range sizes. In Utah, the mean home range size for males was 61 km²; for females it was 24 km². In arid areas, large female home ranges were correlated with widely scattered water sources; during the rainy season, home ranges and movements can increase because of greater availability of watering sources. However, in western Arizona, home ranges decreased with increasing precipitation indicating that forage quality was related to home range area. [16]

Bachelor-ram bands often use gentler habitats with more abundant forage to optimize nutrient intake. Photo: Gregory Smith, Zion-NP, Utah

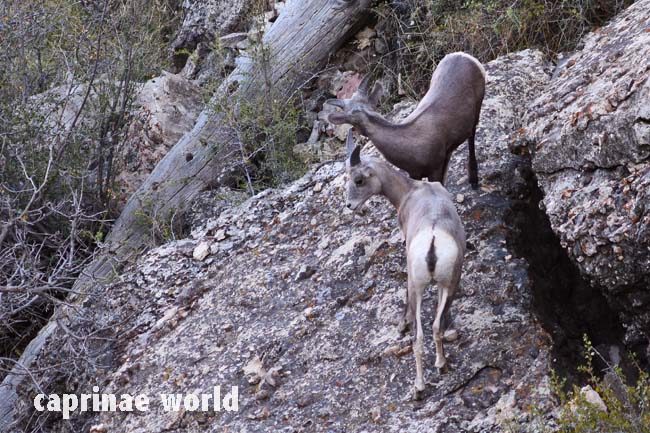

Desert Bighorn Sheep are social animals that live in groups most of the year. They do not gather on any particular range. Groups sometimes combine as they come to water, but summer groups are typically small. The largest groups are spring nursery groups in years of excellent spring forage growth (Wehausen 2011, pers. comm.) After the rut, adult rams generally segregate from ewe-lamb groups. These bachelor-ram bands often use gentler habitats with more abundant forage to optimize nutrient intake and therefore enhance body condition and horn growth. This ultimately leads to increased reproductive fitness. In contrast, ewes spend more time in steep rocky escape terrain for protection from predators to help ensure lamb survival. These areas generally have less abundant forage (Beich et al. 1997). [2]

Colonisation exceed extinctions: Although Desert Bighorn Sheep are said to transfer home range knowledge from one generation to the next, and rarely re-colonize ranges where they have been extirpated, new research over the past two decades has established that natural colonisation in the deserts of California has exceeded extinctions and is filling habitat vacant from an earlier period of higher extinction. [2]

This may mean a revaluation of Geist’s (1971) assumptions: that rams move long distances between mountain ranges in search of ewes during the rut, but will return to their natal home if they do not find other Bighorns; and that ewes rarely follow rams on these journeys. Generally, transplants are necessary to establish resident populations at new sites, especially if inter-mountain corridors contain barriers to successful movement and colonisation. [2]

Status

IUCN classifies the species Ovis canadensis as „least concern“. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [6]

United States: The total number of Desert Bighorns in the US ( 2014) exceeds probably 22.000 individuals. This represents a remarkable recovery from the population lows of the early 1990s, when probably only a few thousand had survived, but still falls short of historic population peaks. [2]

Table 2: Desert Bighorn populations in US states [2]

| state | number of herds / sub-populations | population | large / important populations |

| Arizona | 40 | 4.600 | Black Mountains, southeast of Las Vegas |

| California | – | 4.000 – 4.500 | mountain ranges in the Mojave and eastern Sonoran deserts, Transverse Ranges and the Great Basin Desert (Mono and Inyo Counties) |

| Colorado | – | 480 (in 2010) | Uncompahgre Plateau |

| Nevada | – | 7.400 (in 2014) | Pancake and Toquima Ranges, Gillis and Gabby Valley Ranges, Silver Peak/Monte Cristo, El Dorado Mountains, Muddy and Black Mountains, River Mountains and Mormon Mountains |

| New Mexico | – | 600-700 (in 2011) | Peloncillos (95-110), Hatches (125-155), San Andres (110-130), Fra Cristobal (180-200), Caballos (55-65), Ladrones (35-45), Red Rock captive facility (70) |

| Texas | 7 (in 2010) | 1.500 (in 2010) | in the Trans-Pecos region: Sierra Diablo, Baylor, Beach, Van Horn and Sierra Vieja Mountains |

| Utah | 21 | 2.700 (in 2008) | in the southeastern portion of the state |

Mexico: In 2014 the total number of Desert Bighorn Sheep in Mexico probably approached 10.000 animals. [2] This is a great success story considering that in 1992 the total estimate was just around 4.500 animals. [6] And Desert Bighorn Sheep populations are still increasing in each state that conducts some surveys. Baja California Norte has not done a statewide survey for several years, but recent surveys in localized areas indicate that the population is at least stable. [2]

Table 3: Desert Bighorn populations in Mexico [2]

| state | number of herds / sub-populations | population | large / important populations |

| Baja California | 14 | 1.000 adults (in 1992); 2.500 (in 2000) | Sierras of Cucapa, El Mayor, Juarez, Tinajas, La Pintas, San Felipe, Santa Rosa, San Pedro Matir, Santa Isabel, San Francisco and Las Virgenes |

| Baja California Sur | – | 1.000 (in 2014) | Loreto, Sierra de la Giganta, Sierra Las Tarrabillis, Isla El Carmen (450) |

| Chihuahua | – | – | on several privat ranches |

| Coahuila | – | 150 wild and 250 within enclosure | Los Pilares (breeding facility); Sierra Maderas del Carmen |

| Nuevo Leon | – | – | bin 2008, private ranches started reintroduction efforts |

| Sonora | 30 | 2.800 (in 2009) | western Sonora mountain ranges – particularly from Caborca to Kino Bay; Tiburon Island (800 animals in 2006) |

Threats

Desert Bighorn Sheep partially occur in habitats that are not uniformly distributed and that are increasingly being fragmented, making it impossible for groups to interact and interbreed. [16] Especially in the United States many herds are small (< 100). [6]

Sheep crossing on the eastern base of Sierra Nevada, north of Lee Vining, California. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Habitat enhancement programs and tourist activities can interfere. Sign in Lone Canyon on the border to Canyonlands National Park, Utah. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Exotic ungulates (e.g. Aoudad [7] and Persian Wild Goat [5]) can compete for forage and space, and exotics, together with domestic livestock (including feral burros (Equus asinus) [12], can transmit diseases [16] or alter habitat conditions.

In Mexico main threats are poaching, competition from domestic livestock, and habitat degradation (Sandoval, 1985). [6] In fact the domestic goat industry is one of the limiting factors for Bighorn Sheep in Mexico. [2]

Conservation

The 2000 Wildlife General Law in Mexico provides a new approach for wildlife and habitat management through the establishment of the Wildlife Management and Conservation Unit system (UMA). The UMA allows an individual landowner to construct an enclosed facility for the captive propagation of wildlife. By 2006, 26 UMAs had been established specifically for Desert Bighorn Sheep in Sonora and contained over 700 animals. UMA Pilares in Coahuila and La Guarida in Chihuahua contained more than 120 animals in 2006. Several state governments, namely Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora and Nuevo Leon, obtained the jurisdiction for wildlife management in 2005, and established their own state wildlife agencies. Sonora and Chihuahua devised their state programs specifically for the conservation and management of Desert Bighorn Sheep, with Coahuila and Nuevo Leon taking the same direction. [2]

Although wildlife resources are federal property and are currently managed by the Mexican federal government, almost all of the land is under private ownership. At least seven areas offer special protection for Desert Bighorns by restricting conflicting land use practices (Espinosa 2007) [2]

Recreational Hunting

The economic value of Bighorn Sheep through hunting has led to active management programs and transplanting strategies and, since Desert Bighorns are increasingly appreciated by landowners, the consequence is greater protection of both the animals themselves and their habitats. [2]

United States: Hunting is well regulated and managed in the US. [6] Desert Bighorn Sheep hunters are advised to make themselves familiar with the hunting regulations of the jurisdiction they are hunting in. All jurisdictions in the United States require that Desert Bighorn ram horns be permanently sealed through the insertion of a metal plug into one horn by the appropriate authority. [2]

Table 4: Desert Bighorn hunting permits, applicants and revenues in US states [2]

| state | year hunting was reinstated | permits issued | no of applicants | revenues |

| Arizona | 1953 | 75-90 permits (as of 2014) | – | – |

| California | 1987 | 201 permits (1987-2004) | 85.000 (1987-2004) | US$ 2,3 million (180 sheep) |

| In 2010 eight more hunting zones added: 15 – 20 permits | – | – | ||

| Colorado | 1988 | 5 rams / year (1990-2007) | 800 / year (2014) | – |

| Nevada | 1952 | 175 (in 2008) | – | – |

| New Mexico | 1954 – but not throughout | Peloncillo Mountains: 1-2 / year (1995-2009) | in 2009 odds for drawing a tag were 1996:1 | US$ 2,0 million / year (since 1990) |

| Texas | 1988 | 98 (2008-2014) | – | – |

| Utah | 1967 | 614 (1967-2002); 43 permits / year (as of 2014) | – | – |

Hunting in Mexico: For Mexico is was said in 2008 that hunting needs improvement. [6] Almost all Desert Bighorn Sheep hunts are now fully guided and outfitted with hunter success exceeding 90 per cent. With the exception of the permits that are available through auction, the only permit available are through purchase from outfitters who either own, or have contracted for, the available permits. Any mature ram is legal for harvest. [2]

In Baja California concerns regarding excessive harvest, illegal take, and reported decline of Desert Bighorn resulted in the cessation of all Bighorn hunting in 1990. [2]

Baja California Sur: As of 2014 hunting is permitted in the ejido (hunting area) Bonfil within the El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve on El Carmen Island, and in several ejidos located on communal lands along the east coast of Baja California Sur. Today, there are approximately 450 sheep on El Carmen Island. Currently around 16 permits are available annually. [2]

Chihuahua: By about 1970, wild sheep were probably extirpated in Chihuahua. Today (2014) Desert Bighorns occur on several private ranches. The population is approaching 200 animals. Hunting permits sold in 2009 fetched $50.000 each. [2]

Coahuila: Desert Bighorns were extirpated from this state in the 1950s. In 2000 a Desert Bighorn restoration (fenced breeding facility) was initiated in Los Pilares in the Sierra Maderas del Carmen on the border to Texas. In 2004 a total of 32 animals were released into the wild. Until 2009 the population has grown to 250 within the enclosure and about 150 in the wild. The first Coahuila hunting permit was probably sold in 2010. The first legal hunt in Coahuila in decades followed. [2]

Nuevo Leon: Bighorns had been extirpated long ago. In 2008, privat ranches started reintroduction efforts with sheep from Tiburon Island. [2]

Sonora: Native herds of Desert Bighorn Sheep are found in nearly all the northwestern Sonora Mountain ranges. The entire population in Sonora, including Tiburon Island, consists of about 30 populations, and the 2009 survey produced an estimate of 2.800 free-ranging Desert Bighorn Sheep. (Apparently there are even more animals in enclosures.) The Tiburon Island sheep were introduced in 1975. The 2006 survey estimated nearly 800 animals. The first official hunting season on Tiburon Island was conducted in 1998. About 10 permits are issued annually. The tag auction revenue on the island stood at over US$ 4.500.000 by mid-2010. [2]

Ecotourism

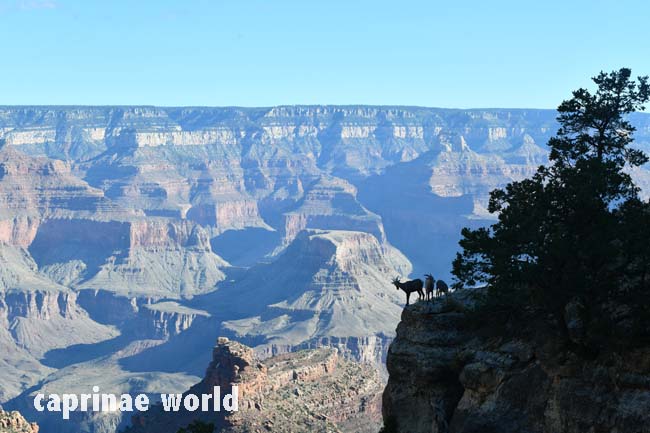

Encounter of two hikers and a ewe on Bright Angel Trail, Grand Canyon National Park. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

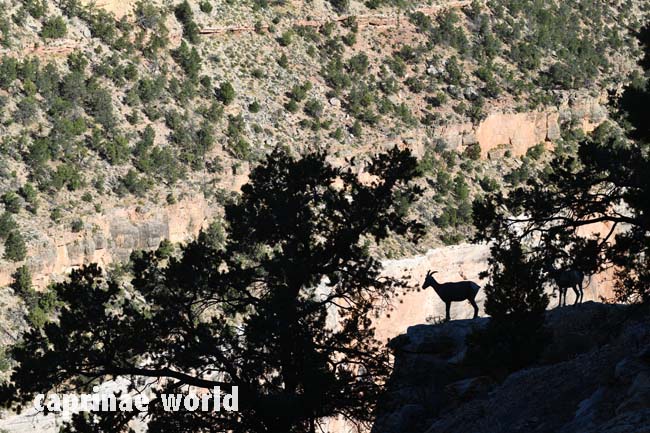

Opportunities to watch Desert Bighorn are numerous. Looking for it often involves hiking through some of the world’s most striking landscapes. Places where it can be found regularly include: [3]

Arizona: the lower slopes of the Grand Canyon (AZ) year-round [3]

According to locals female-young groups can be encountered near the trail head of Bright Angel Trail, Grand Canyon National Park. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Kofa National Wildlife Refuge (AZ) in winter; at Mt. Graham (AZ); they are also often seen on boat tours of Canyon Lake (AZ) [3]

California: the entrance to Borrego Palm Canyon in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park (CA), Barker Dam area in Joshua Tree National Park (CA), Afton Canyon (CA) [3]. Mojave Desert Preserve harbours also a Desert Bighorn population. [3]

Woods Mountains: apparently Bighorn Sheep habitat. But according to locals I interviewed in September 2019 bighorns are very rare and seldom seen in these mountains. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Nevada: a very reliable site is supposed to be Warm Springs, Nevada [John Wehausen, pers. comm.]; other places: main entrance to Valley of Fire State Park (NV) and Desert National Wildlife Refuge (NV). The website of Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge (NV) has a detailed list of locations within the refuge where a sighting is possible. [3]

Oregon: Steens Mt. (OR) in summer [3]

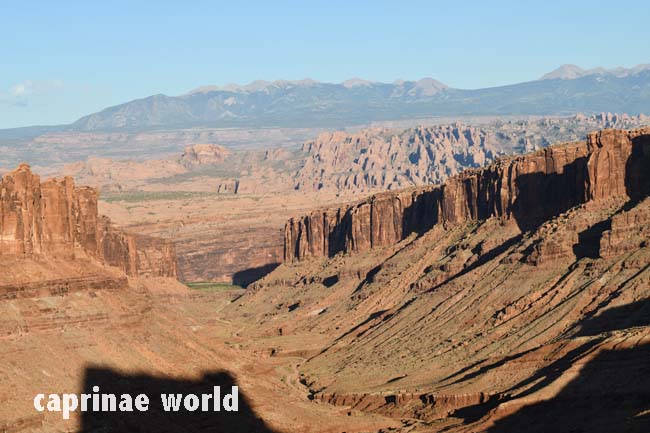

Utah: Arches and Canyonlands National Parks (UT) [3]

Sheep sculpture at the entrance of Arches National Park visitor center: The park administration has made Desert Bighorn Sheep a faunal representative of the area. But according to staff and my own observations the species is hard to find in the park. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

To assist control of poaching, it is illegal, in most US jurisdictions, to pick up the horns of a dead Bighorn Sheep in the field. [2]

Literature cited

[1] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[3] Dinets, Vladimir, 2015: Peterson Field Guide to Finding Mammals in North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[5] Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.), 1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie, Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

[6] Festa-Bianchet, M. 2008. Ovis canadensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15735A5075259. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15735A5075259.en. Downloaded on 19 March 2019.

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[10] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain Monarchs – wild sheep and goats of the Himalaya. The University of Chicago Press

[12] Shackleton, D. M (ed.) and the IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 1997: Wild Sheep and Goats and their Relatives. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 390 + vii pp

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Photo gallery

Rump patches. Note: Dorsal line is intersected. Grand Canyon National Park, September 2019. Photo: Ralf Bürglin