I visited Georgia between 28. 10. and 11. 11. 2023. The main purpose of this trip was to find and photograph Caucasian Chamois. For me it is the last of the ten chamois subspecies, that I wanted to see and photograph.

And I have some ideas concerning this subspecies (more on this two sections down). Being in the Caucasus it is self-evident for a mammal-interested naturalist to look at least for two more endemic species, the Eastern Tur and the Western Tur. The end of October, beginning of November is not the best time to search for animals in the area. Some animals are already in hibernation; the bird migration is largely done. The time of my visit is simply owed to the fact that I wanted to photograph chamois in their winter coat and that you can expect some behaviours related to the species’ mating season.

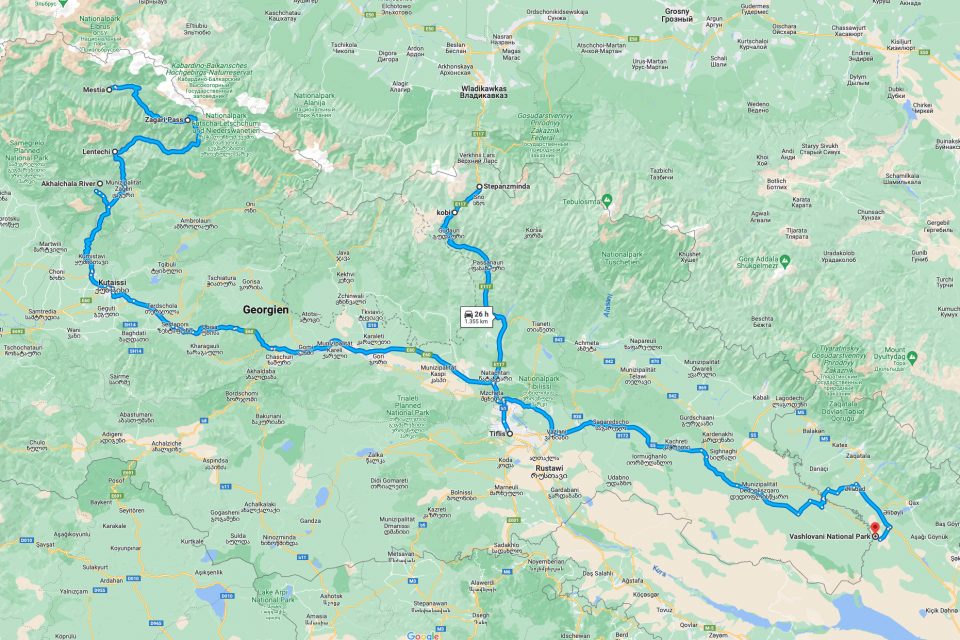

The original plan was to explore these areas: Kazbegi (also spelled Kazbek) and Kobi / Stepantsminda (for Caucasian Chamois and Eastern Tur), Akhalchala / Lentechi (for Caucasian Chamois), Mestia / Svaneti (for Western Tur). (Note that google does not show you the shortest route between Lentechi and Mestia via Zagari Pass and Uschguli.) Early in the planning I skipped Lagodekhi National Park (for Chamois) for the long ascent. I later had to skip Adjara too (an Anatolian Chamois site near the Turkish border) for not having enough time left and cumbersome permit arrangements. This saved me two days, that I used for Vashlovani National Park in the Southeast of the country (for Goitered Gazelle, Golden Jackal, Wolf, etc.). If you combine the distances between the places, where I have been on Google maps, the distances add to 1355 km. (Note, that the last leg to reach Vashlovani NP is not shown correctly. One does not need to drive through Azerbaijan to reach the park.)

About Caucasian Chamois: It is assumed that chamois ancestors probably originated in Asia and spread to Europe during ice age (Wilson and Mittermeier, 2011). According to Iacolina et al. (2021) the closest relatives of chamois are Arabian Tahr (Arabitragus jayakari) and Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) – living in dry environments. Pérez et al. (2022) highlight the hypothesis of three southern glacial refugia in Iberia, Italy, and the Balkans and the posterior recolonization of the northern wards. They also mention that some phylogeographic studies suggested that areas in the south of the Caucasus constituted a further refugium to the East.

Mainly based on these infos I hypothesise that the ancestors of chamois evolved in a rather dry environment and that the more structured / colourful fur pattern of Southern Chamois should be more similar to the original form, whereas the blackish dominated fur of the Northern Chamois is an adaption to wetter environments (Gloger’s Rule). I consider a long, light-coloured gorge patch and a light posterior neck – divided by black lateral neck stripes – to be original features in the winter fur of chamois. In Northern Chamois the gorge patch is usually small. A light-coloured posterior neck is – if at all – only lightly marked (own observation; see also photo below). I hypothesise that in Northern Chamois these features should be more prevalent (in dimensions and numbers) in distribution ranges, which are closest to the assumed development centre of the taxon or respectively closer to a former glacial refugium. The drier parts of the Eastern Caucasus could be such an area. I aimed to see and photograph as many chamois as possible to see if I can get any hints concerning this hypothesis.

Security: Hyperphagia is very likely to strike you. The Georgian kitchen is insanely delicious, very diverse and portions are always too big. Climbing mountains saved me. Next on the danger list is driving. Sitting in a car is probably the most dangerous thing you can do in Georgia. Highways and remote country roads are o.k., but busy two lane roads are murderous. – For weather forecasts guide Nika recommends the following sites: yr.no, meteoblue, accuweather. You reach the mountain rescue via 112. According to Nika they are well organised.

Guiding: For the whole time I went with Nika Kerdikoshvili (You find him on facebook). Jon Hall had already gone with him. He is the most remarkable person I have ever gone with watching animals: dedicated, ambitious, knowledgeable, mountain experienced. He started hunting at the age of seven (his dad had to support his back because of the blowback). He killed his first bear at the age of 14 – but after that Nika decided that killing bears does not make sense. He later studied biology and became a curator at the zoo in Tibilissi. He also works as a birding guide. The only thing that annoyed me is his alarm: a crowing cock. We had a discussion about whether he could at least replace it by the call of a native snow cock. Hopefully in the future …

Mountaineering: You can expect to find chamois in November to range from 2000 m upwards. This meant that in a few cases we could drive up close and then explore an area in a snowless day hike. Hiking boots and trekking poles are advisable, but Nika can also give you a lesson in how to beat the mountains with 20 Euro rubberboots and a self-carved hazelnut stick …

Turs are trickier. They are higher up (Eastern Turs start at 2500 m, Western Turs at 3000 m). Also we managed to reach our first Eastern Turs in an afternoon hike from around 1800 to about 2500 m, I recommend to at least plan two days for Tur observation including setting up a tent. You can hike up in the morning and can then enjoy the late afternoon activities of the animals. The next morning you are in place for the morning show and have the afternoon for the way down. I used my Hilleberg solo tent, Nika had a Northface two-person tent. For November a 3-season sleepingbag is still sufficient. But make sure your air mattress is sufficiently thick. For the hours of relatively physically inactive observation you need a winter down jacket. Be forewarned that observing the ungulates in an upright position is often impossible. Because of their shyness in many cases you must hide behind a rock or even must be lying flat. For longer observations in that position you need a support. (I used my backpack or my mattress wrapped in a protective cover.) For Western Tur in Svaneti you have to expect snow at 3000 m in November. Although you can reach Western Tur habitat without climbing gear an ice axe is recommended for snow covered steep slopes.

28.10. Tbilissi – Stepantsminda via Ivari-Pass

My flight from Basel via Istanbul arrives at 2 am in the Georgian capital. Nika is crazy enough to pick me up at this inhumane time – and start the trip immediately. We stop near the village of Kobi at about 2000 m. We see 6 chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica) at about 2200 m. So we have a plan for tomorrow.

After a night with hardly any sleep I am looking forward to a sweet nap upon our arrival in Stepantsminda. I should have known better and tie Nika onto his car … he goes scouting – and sure enough finds some Eastern Turs (Capra cylindricornis). Heck! So much for the nap, now I already have to climb the mountains. Oh, well …

29.10. Stepantsminda – Kobi – Sno Valley – Stepantsminda

The chamois are still at the site near Kobi. We travers the slope, which has some scattered birches, for about one kilometer. There are six chamois, of which I can photograph two. The first one is a jackpot: Just as expected (see above) it shows a very long gorge stripe – in fact it has the longest one I have ever seen in a Northern Chamois. Very nice!

After that we patrol nearby Sno Valley by car. But no mammals. A few birds still migrate. We see Chaffinch, Yellowhammer, Goshawk …

30.10. Stepantsminda – Kobi – Stepantsminda

We try our luck again at Kobi. But just one lonely male high up is left.

We assume the rest of the chamois has crossed the ridge to the other side of the mountain. So do we. We drive around the corner and hike about five kilometers as far up as 2700 m. The landscape is wild, but except for two Caucasian Grouses and a White-throated Dipper (Cinclus cinclus) we don’t see any noteworthy living creatures.

In the evening Nika scans the slopes above Ioane Natlismcemeli east of Stepantsminda while I detect a squirrel in a nearby pine grove.

31.10. Stepantsminda – Kobi – Stepantsminda

After another morning at the chamois site near Kobi, we now know that poaching pressure must be really high: One disturbance on one day forces the animals to abandon their habitat for several days. That’s not good. And you really have to ask yourself what you should do as a mammal watcher. The animals are not able to distinguish between poachers and naturalists.

On the way back to Stepantsminda Nika detects a new herd of ten chamois in a gorge very close to the road. We park the car and the plan is to approach the animals by climbing the shoulder of the valley. It turns out that this is too difficult, so we try it directly through the gorge. Fortunately there are many rocks to climb up in cover. So eventually I get first pictures. The animals slowly move uphill.

Nika’s skills are amazing. I admire him for his ability of maintaining an overview over a herd. As soon as he sees them, he starts counting. After each sighting he knows exactly how many individuals there have been in a group. In one occasion our chamois climb up behind a rock tower. It is foreseeable that the whole herd will disappear behind that rock to reappear further up. The idea is to wait until the last animal is hidden behind the rock and then sneak up on them from the other side before they show up again. I am sure that the last animal is around the corner and urge zu go. But Nika holds my arm: “Wait! Three are missing.” What? We wait and sure enough three more chamois traverse the site. Without waiting for these, I would have ruined the whole situation.

At around 13:30 we are done with a 500 m ascent and are now at eye level with the chamois at 2510 m. It is nap time and the animals are inactive. I envy them. But my position behind a ridge is to uncomfortable for a nap. My face is burning in the midday sun, while pelvis and thigh lie in the shadow and freeze. Eventually I dare to crawl up so that my whole body lies on the ridge partly covered by grass. The chamois recognise that something is going on, but stay put. I sleep well.

At 4 pm we become busy again. I get my pictures, which proof that basically all animals I have observed show more or less some degree of Southern Chamois traits (more than in any of the hundreds of chamois I have seen so far in other places). In the next step one has to quantify the data and compare populations / subspecies to make this sound science.

Before it’s dark we retreat. In less than one hour we are back to the car. Great day!

1.11. Stepantsminda – hike up the eastern slopes

We park the car again near Ioane Natlismcemeli. In the beginning we follow a path, which is soon lost on the grassy slope. The slope is composed by head sized mounds. (I think in my botany class we called these „tussocks“. Maybe that’s North American? In Germany we call them “Bülten”; singular: Bult). Anyway they are typical for wett soils and while climbing the hill you can use these mounds as stairs. On the other hand, should you miss to step on top of them, you easily slip. There is one 50 m key section, where there is a risk of tumbling down the hill should you slip. Overall the ascent is doable without gear.

We need 4,5 hours (long lunch break included) to reach a ledge at 2700 m, where we set up our tents. At this hight you are already in Eastern Tur country. We enjoy a great view facing Mount Kazbek (5054 m). We leave all the heavy stuff behind, continue our walk and after just another 100 m altitude we detect the first turs. We set-up behind a rock and watch.

Back in camp temperatures stay above freezing. Only my tent gets on my nerves at night. Not properly anchored, it makes a lot of noice in the wind.

2.11. On the eastern slopes – Stepantsminda

We get up at dusk. Nika brews a cup of coffee for each of us. We are still not quite packed, when we suddenly detect a group of six female turs watching us from above, just 30 m away.

We freeze to the ground, which allows us to observe the animals for quite some time. They eventually even allow me to take a few photos before they are gone. Wonderful! Later we don’t have to cover much ground and are able to see different groups of tar.

The most interesting herd consists of 4 old males, 3 young males and 18 females and young. Between the old males there is a lot of wrangling going on. It is still not the peak of the rutting season. As far as we notice there is only one serious clash between two opponents (You definitely hear that!). Luckily my camera captures this moment. From the same observation point we count 28! Caucasian Black Grouse in one flock. Fantastic!

We need to move to relax our bones and walk on. At 3000 m we detect a Stoat, searching for prey within a blockfield. We are lucky to see it running for several minutes. Eventually we loose it in the distance and we decide to continue our hike – just to find a stoat again in front of us. We believe it is a second animal.

We reach the pass at 3160 m. Great views! We see Sno Valley in the distance, that we have already explored. A last couple of Güldenstädt’s Redstart crosses the pass. On the way down we see more turs. Overall it is another very successful day. Nika counts 6 female tur; another group of 19 females; 1 lonely big male; 16 female and 6 male; 4 big males, 3 three-year old, 18 females; 13 snow cocks (including one close up); 28 Caspian Black Grouse.

It is not far to the camp. From there we need 1 h 40 min to reach the car.

3.11. Stepantsminda – Akhalchala

We drive to Western Georgia to a place called Akhalchala (see map).

The last 14 km are a rough off-road path through virgin Caucasian forest – with Nordmann Fir (Abies nordmanniana), Oriental Beech (Fagus orientalis), Caucasian Spruce (Picea orientalis). Gorgeous! It had drizzled the whole day, here in the mountains it is heavy rain. Nika drives a Nissan xterra. I guess it is a serious SUV. Nevertheless it is quite an adventure with slipping and sliding to reach our destination at the end of the forest at 1880 m. There is light in one of the huts. We approach it and Nika talks to a group of loggers. We then just simply move into the neighbouring cabin, where we are dry and can use the oven.

Very basic, but all you need. Lying in the rusty, sagging metal bed lets your bum sink in almost bottomless depths. At least there is enough space underneath to not block the runways of our Murid housemates. Damn! I will never forget to bring a trap along (for IDing the mice).

4.11. Akhalchala – hike to next valley

It has ceased raining. There is a wonderful amphitheatre of mountains around us – but no chamois. It seems, every valley with a road is a lost valley for chamois.

In order to see some, we have to leave this side and climb over into the next valley. In the pass region there is snow and a climbing section.

Nika has to help me and carry my backpack for a few metres. Phew, done! We camp right on top of the next pass at 2750 m, where we can overview three valleys.

But despite a lot of searching we can only spot three chamois. Only one of them is in reach. We save it for tomorrow.

5.11. hike – Akhalchala

We were thinking of approaching the animal at night, but the terrain is to rough. By using headlights we would reveal ourselves. So we try it before sunrise in first light.

We choose a route on the very left, where we have more occasions to hide behind rocks. But we do not come far and the beast is gone. Usually when chamois notice something, they become curious, look at you, ensure that you are a threat and then leave the site quickly. Not here. One view seems to be enough. And the animal is gone. We go around the rock, where it was. From both sides. Nothing.

We climb back to the camp and eat. Chamois numbers are low and the animals extremely shy. Since there is not more to expect, we retreat. We reach the logger’s camp, have another short break, slide down the forest road to reach Mestia in Svaneti in the evening. A Red Fox is the only wild animal we see on the way. At the end of the day we are too tired to go out eating. A shower is all it needs to be ultimately happy.

6.11. Mestia – Svaneti – Mestia

Rain is announced: It is a perfect day to get a rest from the last two days hiking, explore the area and plan the following days. Nika drives me to a place at 3200 m, where you get a good overview and a chance to see tur – this time the Western form (Capra caucasica) – from the car. Dispite the distance (probably two kilometers or more) Nika surely finds a female with a young. My first Western Tur in the wild! It is a start, but I hope to get closer the following days.

North of the airport we detect 20 ravens at a carcass. I believe this is a good opportunity to wait for a fox or some wolves. And there is not much else to do in the rain anyways besides liking Nika’s facebook posts, while he sits beside me … Eventually nothing shows up except a stray dog. I still enjoy the day off.

7.11. Mestia – Svaneti Mountains

Today it gets serious again. We park the car nearby a village at 1650 m. And up it goes. I don’t feel really fit today, but still enjoy the hike through a gorge and a fabulous forest. Close to the tree line we loose the path and have to bushwhack through some Rhododendron thickets. Very strenuous. We finally make it. And just before we reach the open, there is a convenient place at 2490 m to pitch the tents. Nika lights up a fire and soon serves lunch.

After lunch we want to climb higher. A nice day is forecasted, but now it actually snows. We go anyways. Soon we are in the clouds and hope is fading fast. Eventually we are back at the fire, drying wet socks, drinking tea made of melted snow and hoping for next day.

8.11. Svaneti Mountains – Mestia

The embers are still glowing, when I get up. It is -8° C. The fresh snow means more cups of tea. The views are clear. We travel lightly. At 3000 m we reach Western Tur country. Good to be here eventually. It is actually a very small area in Georgia, where this species occurs (In respect of my guide Nika I don’t want to say more.). And it is the only place outside Russia (aside occupied Abkhazia), where it is apparently much easier to see this species. But it’s war …

The snow reaches to the rims of the boots. We leave the ridge and begin to traverse the slopes. Eventually we can see the area, where we saw the turs yesterday from a great distance. We discover tracks and eventually the animals themselves, a herd of 15 males. Bingo! But we are still several hundred metres away. We can at least see, which one is the oldest. It is almost noon, the animals rest. I take a few photos (very bad light), but today is not the day to get more out of the situation. We had planned two days for this part of the trip. We can’t wait until the afternoon and get closer. We are at 3200 m. That makes it a 1550 m descent with heavy gear – including my 800 mm lens. It’s a beautiful hike down. Just after sunset we reach the car.

Originally I had wanted to go to another Chamois site near the Turkish border: Adjara. It turns out, it is a bit more complicated to visit that region involving quite a bit of paper work. Instead we decide to spend the morning in Zcheniszchali Valley between Zagari Pass and Lentechi and look for chamois there from the car and then drive on to reach Vashlovani National Park in the Southeast of the country.

9.11. Mestia – Vashlovani National Park

We leave Mestia while it is still dark. It is very quite on the road. Near the pass we start to scan the area with spotting scope and binoculars. We spend hours on the 65 km long stretch – but with no success. It is unreal. After a hearty breakfast-lunch at Lentechi we are off for Vashlovany on the other side of the country. All-round man Nika organises the permits on the way. It is dark when we arrive in the semidesert. We spotlight until after midnight and find 3 Golden Jackals, 1 fox, a pack of 4 wolves, 2 hares (Lepus europaeus). In a thicket we also detect a cat, which is very likely a Jungle Cat. But we are not able to get close enough. We camp nearby a ranger station. Nika is in his element, lights a fire and a little while later serves fried sausages.

10.11. Vashlovani National Park – Tbilissi

After a short night we are on the dirt road again. The first stretch reminds me very much of North American badlands. The track is often at the same time a temporary water course – on the Arabian peninsula it would be called a “wadi”.

Later the landscape opens into a flat steppe, which is home to the Goitered Gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa). The timing is perfect, since the herd that we approach has a male that is in heat (mating time is early winter). Another great animal!

Yet another highlight is a gathering of Griffon and Cinereous Vultures on the ground. We get quite close. It’s the first time I see the two species together and I am surprised about the bigger size of the Cinereous Vulture. We try to find a carcass, but nothing is found.

After the steppe we enter a gorge to reach a plateau overlocking an area which is unexpectantly quite forested.

Allegedly you can find wolves, bears and lynx here. According to an info board in the park a leopard was confirmed by photo trap for the first time in 2004. Since 2009 no leopards have been spotted again. The prospect of recovery is linked to the recovery of one of its main prey, the gazelle.

This park is so great, that we spend the whole day here, so it is night, when we drive back to Tibilisi. I would have preferred to avoid that because of the traffic, but …

11.11. Tbilissi – Basel

After another short night, my alarm wakes me at 4 am. Nika waits infront of my hotel at 5. He is so kind to drive me to the airport. Great man!

Overall I had a great and successful time in Georgia. Not only did I learn about a country that I hadn’t visited before and enjoyed its nature, I believe I was also able to ascertain that mammal watching can contribute grass roots for science.

References

Iacolina, Laura; Buzan, Elena; Safner, Toni; Bašíc, Nino; Geric, Urska; Tesija, Toni; Lazar, Peter; Cruz Arnal, María; Chen, Jianhai; Han, Jianlin and Šprem, Nikica (2021): A Mother’s Story, Mitogenome Relationships in the Genus Rupicapra. Animals 11, 2021, S. 1065, doi: 10.3390/ani11041065

Pérez, Trinidad; Fernández, Margarita; Palacios, Borja and Domíngue, Ana (2022): Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genomes in the Ten Rupicapra Subspecies and Implications for the Existence of Multiple Glacial Refugia in Europe. Animals 12 (11):1430, dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani12111430

Svensson et al. (2015): Der Kosmos Vogelführer. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart

Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. eds (2021): Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Editions, Barcelona

Giorgi Liparteliani

Eine wunderbare Reise. Sehr gute Bilder und ein toller Text. Ich habe den Artikel zweimal gelesen. Nika ist wirklich der beste Guide für Naturreisen und Wildlife Fotografie.

Danke dafür,dass Du Georgien populär machst. Viel Erfolg noch!!!

Stefan Michel

Großartiger Bericht, tolle Beobachtungen und exzellente Fotos! Danke!