If you follow the Phylogenetic species concept (PSC) – as we do in this chapter – the Afghan Urial is treated as a full species and incorporates the Afghan Urial in the narrower sense, the Transcaspian Urial and the Blanford’s Urial.

Photo of an Afghan Urial from Afghanistan taken by Prof. Gunther Nogge; location: Kabul Zoo, ca. 1971

Name

English common name: Afghan Urial (1), Afghan Red Sheep (Tierpark Berlin).

German: Afghanisches Kreishornschaf (1), Kreishornschaf (Tierpark Berlin),

French: Urial de l‘ Hindu-Kush (1), Mouflon afghan (3)

Spanish: Urial del l‘ Hindu-Kush (1)

Iranian: Quch-e-afghani (1)

Some authors, some of them following the phylogenetic species concept, incorporate the Trans-Caspian Urial (O. v. arkal), Turkmenian Urial, Blanford’s or Baluchi Urial (O. v. blanfordi) (3) and even the Bukhara Urial (O. v. bocharenis).

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

Ovis orientalis cycloceros, Hutton 1842 (1, 6)

Ovis arkal, Eversmann 1850 (4)

Ovis arkar, Brandt 1852 (4)

Ovis vignei varenzovi, Satunin 1905 (4)

Ovis cycloceros (3, 6)

Ovis ammon cycloceros (Tierpark Berlin)

Ovis blanfordi, Hume, 1877. Type locality: Hills above the Bolan Pass, near Kelat, Baluchistan in West Pakistan (6)

Ovis bochariensis, Nasonov, 1914. Type locality: Baljuan, Russian Turkestan (approx. 38° 20′ N, 69° 30′ E) (6)

The name orientalis is based on a hybrid population in north-central Iran and is not usable. (3)

„Kreishornschafe“ from Tierpark Berlin were labelled (and still are, 2018) as Afghan Red Sheep, but today they are actually seen as Arkal (Wolfgang Dreier/Tierpark Berlin, pers. comm.) Subsequently this has let to confusion. For example Castelló (2016) has used images of these „Tierpark Arkals“ to illustrate his Afghan Urial on page 388. Hence his Afghan Urials and Transcaspian Urials are not distinguishable.

Taxonomy

Ovis vignei cycloceros, Hutton 1842

Type locality: Huzzareh (= Hazara) Hills near Kandahar, Afghanistan (6)

Karytype: 2n=58

Reasons for splitting the Afghan Urial as an independent species: Groves and Grubb (2011) have analysed that O. cycloceros arkal, O. bochariensis, and O. vignei are, in fact, distinct. Skull length and breadth, and the frontal arc, contrasted with the low frontal chord, distinguish O. cycloceros especially from the Bukhara Urial (O. bochariensis). (4)

Bukhara Urial and Afghan Urial. Compared to other „neighbours“ the Bukhara Urial differs most widely from the typical Afghan Urial: horns are on average shorter and horn growth is supracervical (they curve above and behind the neck). Photos: Bürglin (l.) / Tallinn; Prof. Gunther Nogge (r.), Kabul Zoo, ca. 1971

Table 1: Scull measurements (mm) of O. cycloceros arkal and O. bochariensis

| skull length | scull breadth | frontal arc | frontal chord | |

| O. c. arkal | ||||

| Mean | 273,39 | 144,47 | 133,00 | 94,12 |

| N | 36 | 34 | 26 | 24 |

| Std dev | 7,530 | 5,440 | 10,855 | 6,707 |

| Min | 252 | 132 | 112 | 81 |

| Max | 297 | 155 | 150 | 108 |

| O. c. bochariensis | ||||

| Mean | 250,40 | 130,90 | 125,50 | 91,13 |

| N | 10 ⚡ | 10 ⚡ | 8 ⚡ | 8 ⚡ |

| Std dev | 12,937 | 9,098 | 9,562 | 5,668 |

| Min | 233 | 118 | 115 | 83 |

| Max | 272 | 151 | 140 | 100 |

The basic information that can be extracted from this table: The sculls of O. cycloceros arkal are on average 3 cm longer and 1 cm broader than sculls of O. bochariensis. For Groves and Grubb (2011) this is one of the main arguments to seperate the two types (phenotypes) as distinct species. (⚡: survey sample size is very small!)

Subspecies

The species „Afghan Urial“ is seperated into two subspecies:

– the Afghan Urial in the narrower sense (Ovis cycloceros cycloceros) – Central and Northeast Afghanistan and West and South Pakistan.

– the Trans-Caspian Urial (Ovis cycloceros arkal) – Northeast Iran, South and Northwest Turkmenistan, and West Kazakhstan. (3)

Differences between the subspecies

While it is generally not easy to distinguish between different Urial types, the distinction between Ovis cycloceros cycloceros and the Trans-Caspian Urial (Ovis cycloceros arkal) seems to be straightforward: O. c. cycloceros has a black ruff and a white bib, while in O. c. arkal both parts – ruff and bib – are white. (3)

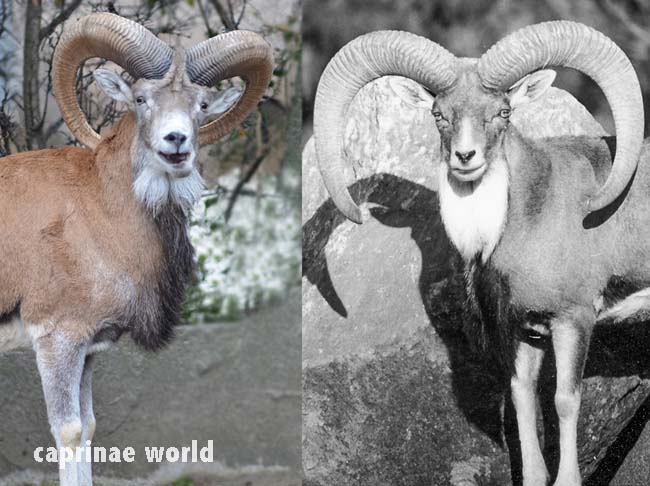

Differences between Arkal and Afghan Urial. Photos: Wolfgang Dreier (l.) / Berlin; Prof. Gunther Nogge (r.), Kabul Zoo, ca. 1971

Distribution

The Afghan Urial (Ovis cycloceros) has a greater distribution than any other type of Urial. It is known from Central and Northeast Afghanistan, West and South Pakistan, Northeast Iran, South and Northwest Turkmenistan and West Kazakhstan (3) and Uzbekistan. The range of Afghan Urial, Transcaspian Urial, Baluchi Urial was once connected. The present more contracted distribution ranges of all three forms are almost certainly separated. (1) They are rarely to be found outside protected areas. (3)

Afghan Urial distribution range if Arkal, Afghan Urial and Blanford’s Urial are pooled as the Afghan Urial in a broader sense. Map Source: OpenTopoMap

Afghan Urial distribution range if only the range of the Afghan Urial in the narrower sense is considered. Map Source: OpenTopoMap

Most of the following data is provided by the IUCN. It dates back to 2008 and is probably outdated:

Turkmenistan: The distribution in this country stretches south-eastwards in scattered populations from the Large (about 39°40’N and 54°30’E) and Small Balkhan mountains north of Nebit-Dagh, through the Kopet-Dagh mountains, in the mountains on the right bank of the Tejen, in an area between the Kushka and Murgab rivers, and in the ravines and rolling hills of Namansaar, Yer Oilanduz (Badkhyz) as far east as Southern Karabil (about 36°20’N and 64°30’N). (7)

Afghanistan: Current data is not available, but Damm and Franco (2014) hold the opinion that Afghan Urial occurs in most central provinces from west to east. (1) Urial populations were known to occur throughout the Hindu Kush and the mountains of central Afghanistan, extending from the Zebak mountains in the north to the Seyah Koh range in the southwest. The largest concentration was in the Ajar Valley Reserve, from where animals were known to migrate into distant valleys near the Band-e Amir National Park. Its presence was established in the Zebak ranges during 1976 surveys, but it was not known how far the species ranged into Badakshan. East of Kabul, the urial was found in the Kohe Safi region of Kapisa Province (Petocz, 1973). Specimens collected from hunters show that its range extended towards the Lataband Pass area near Kabul. The sub-species was also reported from the Safed Koh range in Heart and Badghis Provinces. (7)

Pakistan: A distribution map for this urial in the North West Frontier Province is given by Malik (1987). It shows the occurrence of the subspecies in the Districts of Dera Ismail Khan, Bannu, Northern Waziristan, Karak, Kohat, Orakzai, Kurram, Peshawar, Mardan, Abbottabad, and Swat. Malik (1987) described the populations as being extremely scattered and at low densities in the Districts of Dera Ismail Khan, Bannu, Kohat, Abbottabad and lower -Swat. Urial densities in the Tribal lands are believed to be slightly higher. It is not certain whether animals inhabiting the hills along the west bank of the Indus (Districts Peshawar, Kohat, Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan) are Afghan or Punjab Urial (Schaller and Mirza 1974). Data for animals in this area are included in this account. Urial are widely distributed up to 2,750 m on gentler slopes of the major mountain ranges in Baluchistan. According to the most recent report by Roberts (1985), these include the Chiltan hills (Districts of Quetta and Kalat), the Hinglaj ranges (District Khuzdar), the Karhan hills (District Karhan), the Mekran Coast ranges (District Gwadar), the Takatu hills (Districts of Pishin and Quetta) and the Toba Kakar range (Districts of Pishin and Zhob). On a map published by the Zoological Survey Department (no date) additional areas are indicated: Kirthar range (Districts of Dadu and Las Bela), the mountains north of Nok Kundi (District Chagae), Takht-i-Sulaiman (Districts of Zhob and South Waziristan), the western edge of the Indus at Kalabagh (District Mianwali), the Mahsud mountains (Districts of North and South Warizistan), and the Marri mountains (District Kohlu). The last four areas lie within the distribution area for the subspecies given by Schaller (1977), but were not mentioned in Roberts’ (1985) more recent report. Because of the different and partially contradictory information of the above authors, it appears that the actual knowledge on the status and distribution of Afghan urial north of 32°N is inadequate. The most recent distribution map is given in Virk (1991). In Sind, the Afghan urial occurs in the Kirthar mountains, especially in the Mari-Mangthar range (District Karachi) and in Dumbar, Kambuh and Karchat mountains (District Dadu).

Iran: (Razavi and South Khorasan) (1)

General discription

According to the vast distribution range there is a great variation in body size of Afghan Urial. Males from North-eastern Iran in protected areas without livestock and in lush rangelands can attain weights of 85 kg; males from desert populations in southern Pakistan rarely exceed 40 kg. (3)

Measurements from North-eastern Iran

length / head-body: 135-160 cm – males; 120-134 cm – females (3)

shoulder height: 94-97 cm – males; 82-88 cm – females (3)

hind foot: 37-40 cm – males; 34-37 cm – females (3)

weight: 62-66 kg male, 36-42 kg female (3)

tail: 12-13 cm – male; 11-13 cm – females (3)

Measurements from Pakistan

length / head-body: 127 cm – males; 94 cm – females (3)

shoulder height: 75 cm – males; 72 cm – females (3)

hind foot: 34 cm – males; 32 cm – females (3)

weight: 36 kg male, 26 kg female (3)

tail: 11 cm – male; 10,5 cm – females (3)

Coloration / pelage

upper parts: reddish-buff to yellowish-brown (6)

saddle patch: Males in winter coat from north-eastern Iran and southern Turkmenistan lack a saddle patch, but those from eastern populations usually possess a saddle patch of variable size. (3)

rump: both sexes possess a clearly delineated white rump patch that is restricted to below the base of the tail. (3)

limbs: The back of the hindquarters and lower legs from the „knee“ to the hooves are usually white. (3)

neck: In general, western races have a white throat and neck ruff and eastern forms have a white throat ruff and a black neck ruff. (3)

Horns

Rams have horns which often develop more than a complete arc when viewed from the side. The tips usually bend slightly outwards. The horn growth is normally homonymous (1, 4), but heteronymous horn types are also found in the same populations.

horn length: markedly larger and heavier than in neighboring species / subspecies; length up to 92 cm – (measurements combine O. c. cycloceros and O. c. arkal) (4); over 100 cm in extraordinary specimens. The longest horns are 105,4 cm (1, 6) – the longest of all urial species / subspecies have been recorded from heads originating from the old Waziristan province of British India (now part of Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas. (1)

basal circumference: 20-30 cm (6); 24-30 cm (4); up to 30,5 cm (1)

Today horns over 83 cm in length and 24 cm in girth may be considered very good. (1)

Table 2: Horn length, basal circumference and tip to tip spread of six urial phenotypes. The first three forms are to be included with the Afghan Urial in a broader sense (after Damm and Franco, 2014; measurements in centimeters)

| horn length (median) | horn length (max) | basal circum-ference (median) | basal circum-ference (max) | tip to tip spread (median) | tip to tip spread (max) | |

| O. v. arkal | 92,4 (n=326) |

92 (from Iran); 106, 113, 118 |

27 | 31,2 | 44 | – |

| O. v. cycloceros | 77,8 (n=34) | 105,4 (Waziristan, 1909); 83 (today) | 24,8 (n = 34) | 30,5 (Waziristan, 1909); 24 (today) | 40,3 (n=6) | 61,3 |

| O. v. blanfordi | 74,3 (n=71) | 87,6 (Sindh, 1906); 86 (Balochistan, 2005); 83,8 (Sindh, 2008) | 22,5 (n=71) | – | 22,2 (n=3) | 40,6 |

| O. v. bocharensis | 70,5 (n=39) | 95 | 24,8 | – | – | 28,3 |

| O. v. punjabiensis | 70,8 (n=66); 66,2 (since 1972, n=44 |

98,4 (Attock, 1927); 76,2 (since 1972; n=4) |

23,8 (n=66) | 24,8 (Attock, 1927) | – | 24,1 (Attock, 1927); between 11,4-42,5 |

|

O. v. vignei

|

81,3 (n=33 (Rowland Ward; before 1925)

|

100,3 (1921), 91,4 |

26,9; 27,6 (n=33 (Rowland Ward; before 1925) |

30,5 (1921) | 31,9 (n=28) | 10,8-48,3 (n=28) |

Habitat

The Afghan Urial occurs in a greater variation of habitats than any other form of urial. Populations occur from near sea level to avove 3000 m, but rarely exceed 4000 m. Many occur in degraded habitats grazed by domestic livestock. They usually use rounded, broken terrain at lower elevations, but readily access precipitous terrain as escape cover. Urial densities can vary from less than 1 individual/km² in poor quality habitat overgrazed by domestic livestock to 4,5 individual/km² in good habitat. (3)

Predators

Preadators include Leopards (Panthera pardus), Wolves (Canis lupus), Golden Jackals (Canis aureus), Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and feral and domestic dogs. (3)

Food and feeding

This species is an opportunistic herbivore, feeding on grasses and shrubs. (3)

Breeding

sexual maturity reached: most males by age two, but they do not participate in the rut until 4-5 years of age (3)

mating season: november-december in colder climates; august in southern Pakistan (3)

parturition: April to May in Central Afghanistan (1); February in southern Pakistan (3)

first year of parturition: age two (3)

number of births: twinning can be common, but in years of low precipitation, single offspring prevail. Under extreme drought conditions, females can fail to reproduce and there is high lamb mortality. In contrast, in areas with high forage production, productivity is high. (3)

Activity pattern

Mostly active during morning and afternoons. During the warmest period of the day, they seek thermal cover in tall vegetation. (3)

Movements, home range and social organisation

Except for the mating season, adult males and females segregate into seperate groups. Ram groups are composed ot two-year-olds and older males. Female groups consist of ewes, lambs, yearlings and occasionally younger rams. Ram groups usually number less than 30, but female groups can exceed 100. In areas with high populations, ewe groups consist of 10-49 animals. Adult rams form dominance hierarchies, with older, larger rams dominant over younger rams. Dominance hierarchies probably also occur among ewes. (3)

Population

Populations in all countries have greatly declined. Protected areas rarely have populations exceeding 500. (3) The following data, provided by the IUCN, dates back to 2008 and is most probably outdated (7):

Afghanistan: no estimate

Turkmenistan: The estimate for the total population in the late 1980s and early 1990s was between 10,500 and 11,000 urial. Numbers had increased slightly from the estimates of 7,000 to 9,000 made in the 1970s (Babaev et al., 1978), when there were 2,000 in the Kopet-Dagh Reserve, with about 1,500 in the Badkhyz Reserve (Gorelov, 1978). Although about half the total numbers probably still occur within protected areas, outside them these urial exist mainly in relatively low densities. Recent evidence reports a significant decline in numbers in the eastern Kopet Dagh and in Badkhyz, with only 150 to 200 in Big Balkhan and 300 to 350 in the western Kopet Dagh (V. Lukarevsky, in litt., 1994).

Pakistan: A total population census based on surveys is not available. In the past, Roberts (1985) estimated that perhaps 2,500 to 3,000 Afghan urial lived in Baluchistan, with 1,000 (0.2/km²) inhabiting the Torghar hills of Toba Kakar range (District Zhob) according to Mitchell (1988). About 150 animals inhabit the Takatu hills near Quetta (A. Ahmad, unpubl. Data), and the situation in the Dureji hills (District Zhob) may be a little better (Virk, 1991). Malik (1987) estimated a total of 310 to 340 Afghan urial for the whole of NWFP, whereas the NWFP Forest Department (NWFP 1992) reported a more recent total of only 80 urial (68 from Kohat, two from Mardan and 10 from Abbottabad), suggesting a severe decline over five years. For Sind Province, a census carried out by Mirza and Asghar (1980) estimated a population of 430 urial for Kirthar NP. Based on a census in the Mari-Lusar-Manghtar range and in the Karchat mountains in 1987, K. Bollmann (unpubl. data) estimated between 800 and 1,000 urial (0.26-0.32/km²) for the whole of Kirthar NP. About 150 to 200 animals live in the Mari-Lusar-Manghtar range, and 100 to 150 in the Karchat mountains; i.e. 1.7 to 2.5 urial/km² (Edge and Olson-Edge, 1987). The overall density within the subspecies’ distribution is probably much lower than this. (7)

Threats

Their greatest threats are competition with livestock and illegal hunting. (3)

Afghanistan: On 20 March 2005, Afghan President Hamid Karzai issued Presidential Decree No. 53 banning hunting in any form. (1) In Afghanistan, urials are placed on the country’s first Protected Species List in 2009, prohibiting all hunting and trading of this species within the country. (7) But the ban is almost universally ignored. (1) Most populations in Afghanistan have probably been extirpated. (3)

However, since the increasingly effective enforcement of the Law on Firearms, Ammunitions and Explosives, people have become wary of openly carying firearms. Accordingly, urial populations are considered to have increased in the past several years. However, hunting and trapping of urial continues mostly by a few individuals who attain local prestige as hunters, and by powerful government officals (Shank and Alavi 2010).

In Iran, the remoteness of some areas where Afghan Urial most likely occur have so far prevented a reliable survey. (1) Caprinae species (urial and wild goat) are the only game mammals in Iran that can be hunted under licences issued by the Department of the Environment. The hunting season for Caprinae lasts four months beginning each year in September, but each licence is valid only for five days from its date of issue. Each hunter can obtain up to four licences per hunting season, and may shoot three males and one female. Unfortunately the exact numbers of Caprinae shot each year by hunters are not available. According to recent data, between 2,200 and 3,200 licences were issued each hunting season, and a rough estimate of the number Caprinae legally shot each year would be between 2,000 to 3,000 animals. However, more than twice this number are estimated to be killed by poachers annually. Hunting is permitted in protected areas but requires a special licence. Because Caprinae populations are not harvestable in most areas, licences are almost never issued for protected areas. (7)

Conservation Status / Trophy hunting

Turmenistan: Approximately half the total population lives in protected areas in Turkmenistan. Kopet Dagh Nature Reserve was established primarily for preservation of this subspecies, and they are also found in Siunt-Khasardag and Badkhyz Nature Reserves. (7)

The Torghar Concervation Project (TCP) is critically important for the conservation of Afghan Urial in Pakistan. The goal of this sustainable use project is to bring benefits to the local people to prevent them from poaching. Initially, TCP established a game guard program at Torghar in 1986 with the involvement of the local communities. Over the years the Torghar project has emerged as an exemplarily successful model of biodiversity conservation through sustainable use. A complete ban on unauthorized hunting has been enforced. Controlled hunting of trophy animals was seen as a critical component of the plan for two basic reasons: first, to generate the revenue necessary to support the game guard program; second, to convice the game guards and other local people that their economic well-being was directly tied to the abundance of urial (and markhor), motivating them to give full protection to both species. (1)

Systematic trophy hunts by foreign hunters (mainly from Europe) have taken place every year from 1986 onwards and the proceeds were used to hire more game guards and provide developmental assistance to the local community and tribesmen as areward for their conservation efforts. older animals were carefuly selcted for hunting so that the herds‘ breeding performance was not affected. The Society for Torghar Environmental Protection (STEP), an officially registered nongovernmental organization under Pakistani law, receives an annual hunting quota of five Afghan Urial.

Surveys between 1994 and 2005 show that the estimated urial populations have increased from 1.173 to 3.146 (Shafique 2006). The developmental schemes which were funded with the proceeds of trophy hunting benefited the entire community. The people of Torghar recognized that conservation, when practiced correctly, brings pride and economic benefits to the entire community and results in bright ecological prospects. (1)

Ecotourism

not a factor

Literature Cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine and Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag.

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princton University Press.

(6) Valdez, Raul, 1982: The Wild Sheep of the World. Wild Sheep and Goat International, Mesilla, New Mexico.

(7) Valdez, R. 2008. Ovis orientalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15739A5076068. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15739A5076068.en. Downloaded on 12 March 2018.