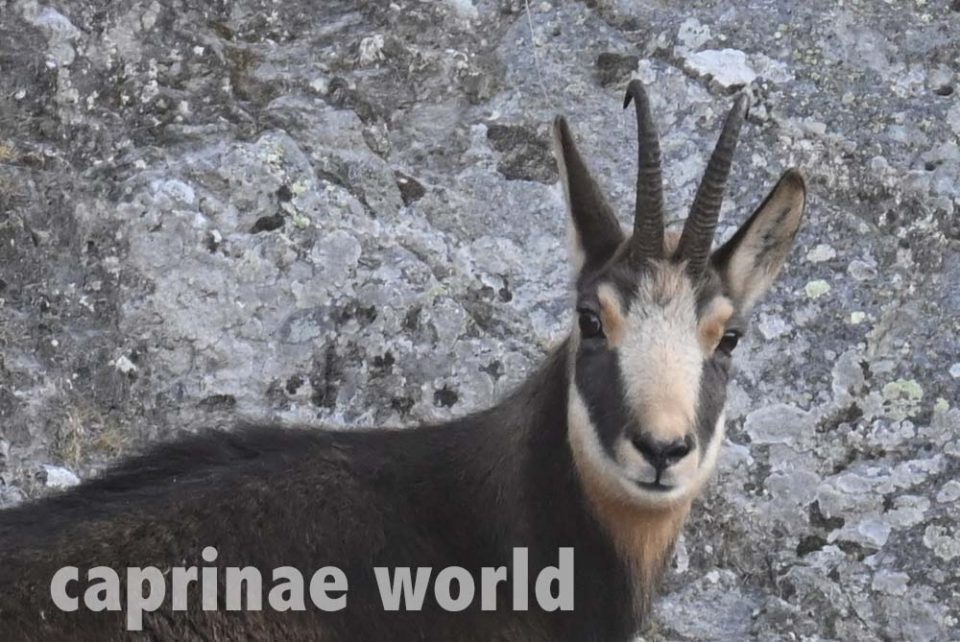

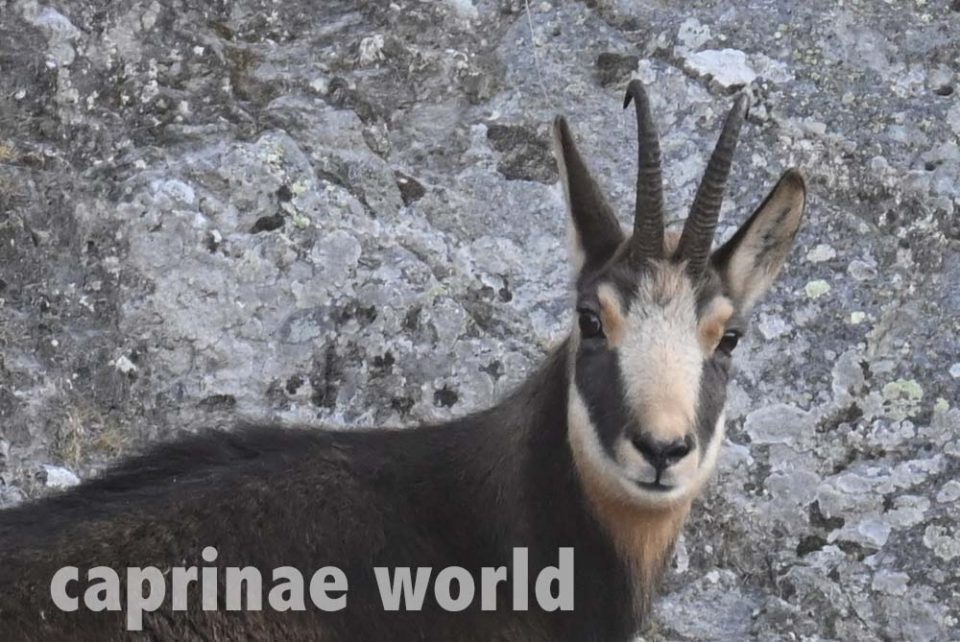

This phenotype is probably not much different from the Alpine Chamois, but does show a few interesting morphological features. Caprinae world is the only place, where these are currently (2024-04-24) presented.

Names

Armenian: Kovkasyan lernayts [2, 5]

Azeri (Azerbaijani language): Köpkör, Köpkər, Kiopkæz, Gara paça, Garapacha [5]

English: Caucasian Chamois [5]

French: Chamois de Caucase [2, 5]

Georgian: shych’i [5]

German: Kaukasus-Gämse [3]; Kaukasusgams [5] – (editor’s note: hunter’s jargon)

Ossete (Ossetian language / Eastern Iranian language): Archvi, Psiti [5]

Russian: Tschjorni kosjol (editor’s note: meaning Black Buck) [77]

Spanish: Rebeco caucásico [3] , Rebeco caucasico [5]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms:

Rupicapra tragus caucasica, Lydekker Ward’s Record of Big Game, ed. 6 p. 338, 1910. Type locality: Caucasus [5]

Taxonomy

| french | english | german |

| En résumé, par l’analyse minutieuse, on trouve au Chamois du Caucase des caractères qui lui sont propres, mais qui ne sont jamais éclatants. Cette forme est morphologiquement très rapprochée de la forme type des Alpes. J’en fais une sous-espèce faible. | In summary, by careful analysis, one finds in the Caucasian Chamois characteristics which are specific to it, but which are never striking. This taxon is morphologically very close to the typical form of the Alps. I make it a weak subspecies. | Zusammenfassend finden wir bei sorgfältiger Analyse bei der kaukasischen Gämse Merkmale, die für sie spezifisch sind, aber niemals auffallen. Diese Form kommt morphologisch der typischen Form der Alpen sehr nahe. Ich mache sie zu einer schwachen Unterart. |

Later it was more about whether the Caucasian Chamois should be considered as a subspecies of R. rupicapra (Alpine Chamois) or as a full species, under R. caucasica, by some authors.

The justification for the separation of subspecies asiatica and caucasica has also been questioned for a long time (Kumerloeve 1974; Heptner and Nasimovic 1966; Lovari and Scala 1984). [5]

Groves and Grubb (2011) believe that asiatica and caucasica are “almost certainly” synonyms. They further write: “On geographic grounds, it does seem probable that R. asiatica, the chamois of Turkey and the Caucasus, is distinct from others, but more evidence is needed.” [7]

Damm and Franco (2014) suggest that the separation into two geographical rather clearly separated phenotypes – asiatica and caucasica – „makes good conservation sense and opens management options.” [5]

Diploid chromosome number: 2n = 58 [5]

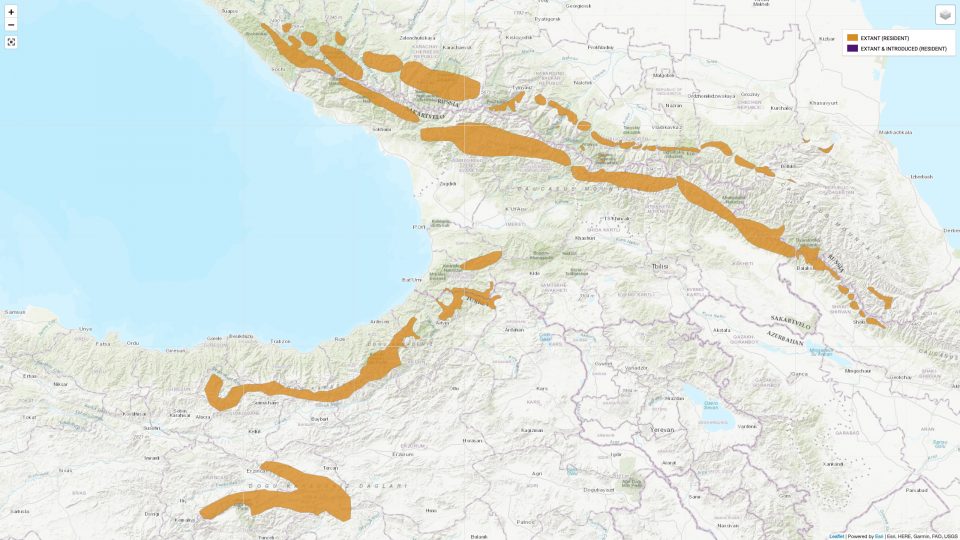

Distribution

The distribution of the Caucasian Chamois is not easily outlined, since in the first place the taxonomy is not clear (see above) and secondly if caucasica and asiatica are two different taxa it is not clear how to draw the distribution boundary between the two.

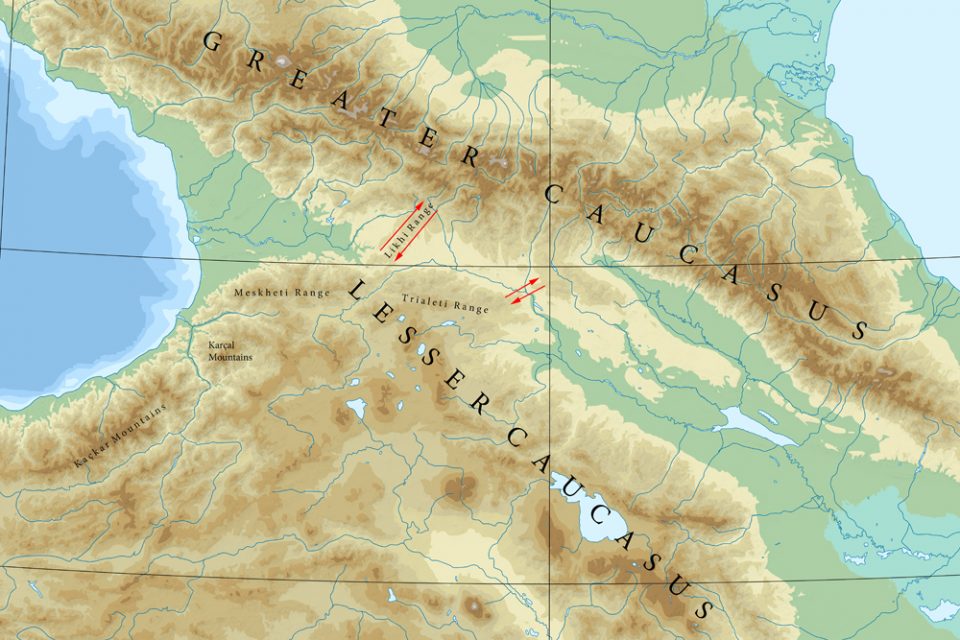

According to IUCN the subspecies R. r. caucasica is distributed in the Greater Caucasus and Lesser Caucasus, encompassing areas in southern Russia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. In the Greater Caucasus, the chamois sporadically inhabits all three highest ranges, and sometimes occurs at lower altitudes. It’s distribution in the Lesser Caucasus is said to be confined to the Adjara-Imereti Mountain Range (Vereshchagin 1947, Gurielidze 2015). [1] (Editor’s note: The Adjara-Imereti Mountain Range is tantamount to the Meskheti Range, see map below.)

On the other hand Damm and Franco (2014) confine the distribution area of the Caucasian Chamois to the Greater Caucasus exclusively. They assume the northernmost presence of the Anatolian Chamois in the Lesser Caucasus, west of Georgia’s Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park. [5]

The general question that arises is: Is it justified to allocate the Lesser Caucasus – or parts of it – to the distribution area of the Anatolian Chamois? From a geographical point of view there could be – or could have been – a better connectivity be given between the north-easternmost mountains in Turkey and the southwestern parts of the Lesser Caucasus in Georgia than between the Lesser Caucasus and the Greater Caucasus simply because the distance is shorter and because the level of connectivity of suitable habitat may be better.

The Lesser Caucasus is geomorphologically connected to the Greater Caucasus by the Likhi (Surami) Range, which extends north from the town of Borjomi. Looking at the topography it can be assumed that the south of the Likhi Range is less favourable for chamois. An impression of the area is received at Surami Pass (with 949 m the lowest pass within the Likhi Range; about 40 km north of Borjomi) or at nearby Rikoti Pass (996 m).

In 2023 a Chinese Company was in the process of expanding the road that goes over the pass – also building a tunnel, which should be advantageous for animal movement.

Could there be a second corridor for chamois between the Lower and the Greater Caucasus? Shackleton (1997) writes that chamois is also distributed within the Trialeti Range, which extends from Borjomi eastwards towards Tbilisi. Damm and Franco (2014) state that “it is unknown whether chamois are still present in the area east of Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park.” Nika Kerdikoshvili, Georgian biologist, told me that there are no more chamois left in the Trialeti Range (pers. comm, 2023). However the northeastern end of the Trialeti Range could have been a second stepping stone towards the Greater Caucasus. Northeast of Tbilisi the mountains continue with the Saguramo Range (including Tbilisi National Park and Mt. Saguramo, with 1392 metres the highest mountain in the area). Today it has to be assumed that the northern outskirts of Tbilisi, highway E60 and the river Kura constitute a barrier for any animal movement.

Given that Anatolian Chamois and Caucasian Chamois are two different taxa, another interesting question arises: Is or was there a zone of overlapping and where could it be? If the Caucasus Chamois is restricted to the Greater Caucasus and the Anatolian Chamois occurs in the Western part of the Lesser Caucasus, then the connecting mountains in between are a place to look for. The next possible population south of the Likhi-corridor and east of the Meskheti Range is the area of the Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park. And here it is actually, where Damm and Franco (2014) assume the “zone of intergrading or overlapping” between asiatica and caucasica. Unfortunately, it seems there are no chamois left in this area (pers. comm. Nika Kerdikoshvili 2023).

A hint that chamois are or have been distributed further southeast along the Lesser Caucasus comes from some records of chamois in northern Armenia (Vereschagin 1959, in “Mammals of the Caucasus” p. 361-362), but apparently they became extinct in the 1930s. However, some Azeri researchers assume that chamois may still occur in the northern, forested part of the eastern Lesser Caucasus (Zazanashili 2011, pers. comm. to Damm and Franco). [5]

Description

The following list shows how difficult and contradictory the description of this taxon is – even if it’s just the size:

- F. Siegmund writes that the Caucasian Chamois is smaller than that of the Alps. [4]

- Max Noska notes no difference between the two forms with regard to height and stature, absolutely identical. [4]

- According to Damm and Franco (2014) this “phenotype is probably on average larger than the Alpine Chamois.” [5]

- In Castelló (2016) the “probably on average” mentioned in Damm and Franco (2014) is gone. He simply states that the chamois is „slightly larger than the Alpine Chamois.„ [3]

| french | english | german |

| En 1901, dans The great and small Game of Europe, R. Lydekker fait du Chamois du Caucase une variété de l’appelle Rupicapra tragus var. d. M. Noska avait déja attiré l’attentation sur cette forme dans uns monographie remarquable parue en 1895. Néanmoins, C. K. Satunin en 1896, Satunin et Radde en 1899, Moriz von Decky en 1905, Trouessart en 1910, K. Stoffel en 1912, A. Martenson en 1912 ne lui trouvent pas de caractères différentiels précis. Cependant, Lydekker en fait une sous-espèce qu’il nomme Rupicapra tragus caucasica en 1910 et Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica en 1913. F. Siegmund, cité par Noska, écrit que le Chamois du Caucase est plus petit que celui des Alpes Max Noska ne note aucune différence entre les deux formes en ce qui concerne la taille et la stature, absolument indentiques. | In 1901, in The great and small Game of Europe, R. Lydekker made the Caucasian Chamois a variety of the called Rupicapra tragus var. d. M. Noska had already drawn attention to this form in a remarkable monograph published in 1895. Nevertheless, C. K. Satunin in 1896, Satunin and Radde in 1899, Moriz von Decky in 1905, Trouessart in 1910, K. Martenson in 1912 did not find any precise differential characters for it. However, Lydekker made it a subspecies which he named Rupicapra tragus caucasica in 1910 and Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica in 1913. F. Siegmund, quoted by Noska, writes that the Caucasian Chamois is smaller than that of the Alps Max Noska notes no difference between the two forms with regard to height and stature, absolutely identical. | 1901 machte R. Lydekker in The great and small Game of Europe die kaukasische Gämse zu einer Varietät der sogenannten Rupicapra tragus var. d. M. Noska hatte bereits 1895 in einer bemerkenswerten Monographie auf diese Form aufmerksam gemacht. Dennoch fanden C. K. Satunin 1896, Satunin und Radde 1899, Moriz von Decky 1905, Trouessart 1910, K. Martenson 1912 keine genaue Differentialzeichen dafür. Lydekker machte sie jedoch zu einer Unterart, die er 1910 Rupicapra tragus caucasica und 1913 Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica nannte. F. Siegmund, zitiert von Noska, schreibt, dass die kaukasische Gämse kleiner ist als die der Alpen Max Noska stellt keinen Unterschied zwischen den beiden Formen hinsichtlich Größe und Statur fest, absolut identisch. |

The following measurements show ranges rather than means, which makes comparing taxa difficult.

head-body males: 125-135 cm [5, 10] – compared to Alpine C.: 110-130 cm [10]

head-body females: c. 96 cm [5, 10]

tail: 8-10 cm [10]

shoulder height: 78-86 cm [5, 10] – compared to Alpine C.: 70-85 cm [10]

weight: males 30-50 kg [5, 10] – compared to Alpine C.: 25-60 kg [10]

females: 25-42 kg [5, 10]

It is also interesting to note that the above figures correspond exactly to those of the Anatolian chamois.

Scull

“larger cranial dimensions for caucasica than those of the Alpine subspecies”. [5 – quoting Koubek and Hrabe (1983)]

The nasal bones are lacking a distinct lachrymal process and a small persistent lachrymal fissure is present. In the West European races and in the Anatolian Chamois there is a small lachrymal process to the nasals, and the lachrymal fissure obliterates early. [5 – quoting Lydekker (1913)]

| french | english | german |

| Je remarque sur cette tête osseuse la petite largeur du lacrymal à sa partie moyenne. La fontanelle naso-lacrymale est complètement fermée. La suture naso-maxillaire, longe de 1,8 cm, est très intime. L’os nasal très dévelopée a une forme triangulaire allongée. Je note l’importance en largeur de l’ouverture des fosses nasales: 3,65 cm. | I notice on this bony head the small width of the lachrymal bone at its middle part. The nasolacrimal fontanel is completely closed. The naso-maxillary suture, 1.8 cm long, is dead smooth (not gross). The highly developed nasal bone has an elongated triangular shape. I note the importance in width of the opening of the nasal cavities: 3.65 cm. | Ich bemerke an diesem knochigen Kopf die geringe Breite des Tränenbeins in ihrem mittleren Teil. Die Nasen-Tränen-Fontanelle ist vollständig geschlossen. Die 1,8 cm lange Naso-Maxillar-Naht ist absolut glatt. Das hochentwickelte Nasenbein hat eine länglich-dreieckige Form. Ich bemerke die Bedeutung der Breite der Öffnung der Nasenhöhlen: 3,65 cm. |

Colouration / pelage

The Asia Minor Chamois (asiatica and caucasica are seen as one species here) is similar in body coloration to Alpine Chamois. [10]

Couturier (1938) goes a bit more into detail:

| french | english | deutsch |

| La robe n’offre pas des caractères bien particuliers. Elle est cependant un peu plus claire. La tache claire du cou est dans sa partie inférieure, d’un jaune orange. Toutes les zones claires de la tête sont orange pâle. J’ai noté que la région claire du front se continue jusqu’a la base des cornes. La barre sombre des joues, limitée en bas par une ligne horizontale, est d’un brun grisâtre. Le contraste entre les parties claires et les zones foncées de la tête n’est pas três marqué. L’habit hivernal est brun foncé, les plages claires blanchâtres, la queue noire. On cite des cas d’albinisme partiel. | The dress does not offer very particular characters. However, it is a little lighter. The pale patch of the neck is in its lower part, of an orange yellow. All light areas of the head are pale orange. I noted that the light region of the forehead continues to the base of the horns. The dark bar of the cheeks, bounded below by a horizontal line, is grayish brown. The contrast between the light parts and the dark areas of the head is not very marked. The winter coat is dark brown, the pale areas whitish, the tail black. Cases of partial albinism are cited. | Das Kleid bietet keine sehr besonderen Eigenschaften. Allerdings ist es etwas heller. Der helle Fleck am Hals ist im unteren Teil orangegelb. Alle hellen Bereiche des Kopfes sind blassorange. Ich bemerkte, dass sich die helle Region der Stirn bis zur Basis der Hörner fortsetzt. Der dunkle Balken der Wangen, der unten von einer horizontalen Linie begrenzt wird, ist graubraun. Der Kontrast zwischen den hellen Teilen und den dunklen Bereichen des Kopfes ist nicht sehr ausgeprägt. Das Winterfell ist dunkelbraun, die hellen Partien weißlich, der Schwanz schwarz. Fälle von partiellem Albinismus werden angeführt. |

Comment on Couturier’s statements above: It is not clear how Couturier determines that the fur should be lighter overall. The fact that the lower part of the throat patch and other light areas on the head are orange-yellow can also be seen in other subspecies of the northern chamois. One can also see in other chamois that the light forehead extends to the base of the horn. The fact that the contrast between the light and dark parts of the face mask should not be very pronounced is refuted by the photos shown below. If you wanted to scientifically test Coutourier’s statements concerning colour patterns of the pelage, you would have to analyse the coloration patterns of a large population, define an average and then compare the results with other subspecies.

winter pelage colour: chocolate brown [2, 5]

summer pelage colour: smooth tawny or reddish brown to fox red with a dark stripe running along the spine. [2, 5]

underparts: pale [2, 5]

legs: usually darker than body [2, 5]

head: facial mask reaches up to the back of the neck; coloration at the base of the horns is paler than in Carpathian Chamois. [2, 5] Orange patches appear on the light area of face above the nose and eyes, as well as behind the tip of the chin. [5]

Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Alpine Chamois from Berchtesgaden National Park, Germany. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

throat patch: large, whitish above and orange below [5 – quoting Lydekker (1913)]

Horns

| french | english | german |

| F. Siegmund, cité par Noska, écrit que le Chamois du Caucase est plus petit que celui des Alpes, que ses cornes sont bien droites, très rapprochées à leur naissance et forment un crochet très net. Pour lui ((Noska)), le Chamois du Caucase a les cornes plus petites. Chez les femelles, les étuis presque parallèles se terminent par un crochet insignifiant, ce qui ne les empêche pas d’avoir une longeur parfois supérieure à celle de étuis des mâles. Lydekker souligne les caractères suivants et s’en sert pour la descriptions de sa sous-espèce: cornes du mâle courtes et trapues, s’élevant presque verticalement avec peu de divergence … Couturier conclut: … on se rend immédiatement compte de la faiblesse des chiffres et on peut affirmer que le Chamois du Caucase a des cornes nettement moins fortes et moins divergentes que celles de la forme des Alpes. | F. Siegmund, quoted by Noska, writes that the Caucasian Chamois is smaller than that of the Alps, that its horns are very straight, very close together at their base and form a very clean hook. For him ((Noska)), the Caucasian Chamois has smaller horns. In the females, the almost parallel sheaths end in an insignificant hook, which does not prevent them from having a length sometimes greater than that of the sheaths of the males. Lydekker underlines the following characters and uses them for the descriptions of his subspecies: male horns short and stout, rising almost vertically with little divergence… Couturier concludes himself: … we immediately realize the low numerical values and we can affirm that the Caucasian Chamois has horns that are clearly less strong and less divergent than those of the Alpine form. | F. Siegmund, zitiert von Noska, schreibt, dass die Kaukasische Gämse kleiner ist als die der Alpen, dass ihre Hörner sehr gerade sind, an ihrer Basis sehr dicht beieinander liegen und einen sehr sauberen Haken bilden. Für ihn ((Noska)) hat die Kaukasische Gämse kleinere Hörner. Bei den Weibchen enden die fast parallelen Scheiden in einem unbedeutenden Haken, was nicht verhindert, dass sie manchmal länger sind als die Scheiden der Männchen. Lydekker hebt die folgenden Merkmale hervor und verwendet sie für die Beschreibungen seiner Unterart: männliche Hörner kurz und stämmig, fast senkrecht ansteigend mit geringer Divergenz … Couturier zieht selbst folgende Schlüsse : …erkennen wir sofort die geringen Zahlenwerte und können bestätigen, dass die kaukasische Gämse Hörner hat, die deutlich weniger stark und weniger divergierend sind als die der alpinen Form. |

Horns are short and stout, rising nearly vertically and with only moderate divergence. [5 – quoting Lydekker (1913)], e.g. they are shorter and more compact than that of the Alpine Chamois, with a relatively narrow spread. [5]

horn length mean:

20,6 cm (n=71) – hunted chamois (SCI and RW) [5] – The values may refer to males. However, the text does not provide any clarity regarding gender.

23,14 cm (males, n=7) – according to M. Noska (see table below)

22,346 (males, n=12) – according to Lovari and Scala, 1984) (see table below)

horn length males maximum: 27 cm (see table Lovari and Scala, 1984); 25 cm (see table Nosca below); over 25,4 cm is rare [5]

female horns: slightly shorter, less hooked and thinner on average [5]

horn basal circumference (mean): 8,6 cm [5]

| female 1 | female 2 | male 1 | male 2 | male 3 | male 4 | male 5 | male 6 | male 7 | |

| length | 24,0 | 18,0 | 23,5 | 24,0 | 24,5 | 24,0 | 21,0 | 20,0 | 25,0 |

| height | 18,0 | 11,5 | 15,0 | 16,0 | 14,0 | 12,0 | 17,0 | ||

| base circumf. | 7,2 | 7,2 | 9,0 | 8,7 | 9,0 | 9,0 | 9,0 | 8,5 | 9,0 |

| dist. at base | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 1,0 | 2,0 | 1,0 | 1,5 | 1,5 | 1,0 |

| gap at top of curvature | 6,0 | 4,5 | 10,5 | 7,5 | 10,0 | 10,5 | 8,0 | 11,0 | 10,0 |

| 1 frontal length of horn | 2 dist. betw. horn tips | 3 min dist. betw. horn tips | 4 min dist. betw. horn bases | 5 min dist. betw. horn bases | 6 antero- posterior diam. at base | 7 trans- verse diam. at base | 8 min dist. betw. horn tips and base | 9 base circum- ference | |

| min. value | 20,300 | 5,000 | 5,200 | 1,400 | 08,00 | 2,500 | 2,000 | 9,500 | 7,300 |

| max. value | 27,000 | 9,600 | 10,100 | 4,600 | 2,200 | 3,000 | 2,700 | 12,900 | 9,000 |

| mean | 22,346 | 7,208 | 7,338 | 2,508 | 1,162 | 2,731 | 2,454 | 11,154 | 8,231 |

| stand. deviat. | 18,41 | 13,38 | 12,77 | 7,87 | 3,75 | 1,49 | 1,94 | 11,14 | 5,04 |

| french | english | german |

| Ce qui m’a le plus frappé à propos des cornes, c’est leur richesse en annelure d’ornementation, annelures serrées, très saillantes et rencontrées jusqu’à la partie la plus élevée de la courbure. | What struck me the most about the horns was their richness in ornamental ringing, tight ringing, very prominent and met up to the highest part of the curvature. | Was mich an den Hörnern am meisten beeindruckte, war ihr Reichtum an Schmuckringen, engen Schmuckringen, sehr hervorstehend und bis zum höchsten Teil der Krümmung auftretend. |

Field characteristics

Reliable features for distinguishing Caucasus Chamois from tur: The comparably light body, the different shape and black colour of the horns, the intensely bright fox-red colour of the pelage in summer and the black-brown fur in winter, as well as the drawn-out hissing whistle. [77]

The feces is in the form of small elongated nuts (1-1.2 x 0.8 cm), which are smaller than those of turs and Bezoar goats. The Chamois’s game trails, which they use alone, are narrower and less worn than those of the wider built turs. [77]

Habitat

The Caucasian Chamois lives in areas with a very humid climate and a large amount of precipitation in the form of snow (Western Caucasus) as well as in relatively dry areas with little snow (Dagestan, Armenia, etc.). [77]

The vertical distribution varies greatly: it ranges from 400 to 3500 meters (Northwest Caucasus) and even up to 4000 meters in Transcaucasia. [77]

(Editor’s note: The term Transcaucasia is confusing. One might think that it refers to the area beyond – from a Russian perspective, south – of the Greater Caucasus. But the term South Caucasus also appears as a synonym for the Transcaucasus. This in turn suggests that the South Caucasus is part of the Greater Caucasus. In fact, according to Wikipedia, the South Caucasus includes not only the Lesser Caucasus and the plains south of the Greater Caucasus, but also southern parts of the Greater Caucasus. The fact that the maximum altitude distribution of the Caucasus chamois of 4000 meters must be in the southern part of the Greater Caucasus can also be concluded from the fact that there is no peak south of the Greater Caucasus that reaches this height. The highest peak in the Lesser Caucasus is Gamış dağı in Azerbaijan at 3724 meters.)

Chamois by the sea: At the end of the 19th century, small herds gathered in winter near Khosta and Gelendzhik (Black Sea coast) 150 to 200 meters above sea level. [77]

In the Western Caucasus, chamois can be observed in a wide mountain belt in summer, but are particularly numerous at this time of year at altitudes of 1700 to 2500 meters, in alpine and subalpine meadows and in the upper third of the mountain forest belt. The animals are drawn to very steep and rocky slopes and only where people do not disturb them much, do they sometimes go out to graze on open alpine pastures with relatively gently sloping slopes, for example on mountain plateaus, in wide trough-shaped high valleys and the like. Turs are extremely rare to find in such places. The chamois avoid shady gorges, where the Turs often descend to rest for the day in summer. The habitats of both species therefore often do not match.

In Dagestan (Eastern Caucasus) Rupicapra is usually found very high in the alpine belt of mountains in summer time, where it can be observed even higher than the Bezoar Goats and Turs (Heptner and Formozov 1941). To some extent this is connected with the high location of the eternal snow border in Dagestan. In many areas of the Caucasus, especially where chamois were heavily persecuted by hunters in the past and the alpine pastures are easily accessible to humans, most spend the whole year in the forest belt of the mountains between 700 and 2000 meters above sea level (Ossetia, catchment area of the Alasani river and others). Animals that live in alpine meadows in summer usually descend into the forest in winter.

They occur in the alpine zone in September-November and lowest elevations during December-May. [10]

Predators / Mortality / Competitors

Gray Wolves (Canis lupus) and Lynx (Lynx lynx) are major predators. Chamois remains were found in 12 % of wolf droppings and 18 % of lynx scats. Domestic dogs can be major predators in some areas [6, 77]. In snowy winters, chamois sometimes end up in biotopes that are less suitable for them, where they then become victims of wolves. [77]

Wolf predation does not affect the chamois population on the reserve. The number of wolves increases with an increase in the chamois population density to 15–20 ind./1000 ha. [6]

In mountain pastures, chamois can often be seen grazing in close proximity to a bear, but the bear makes no move to attempt an attack and the chamois do not make any attempt to escape. However, in spring (editor’s note: when young are born) it is quite possible for bears to attack (Nasimovic 1940). [77]

Dinnik (1910) considered the Leopard to be one of the most dangerous enemies of the chamois. Today it is very rare in the Caucasus and cannot cause any damage to the population. [77] (Editor’s note: „Today“ is 1966, but probably since then not much has changed.)

In very snowy winters, such as in 1910/11 and 1931/32, cases of chamois dying from avalanches increases (Western Caucasus; Nasimovic 1939) [77]. Another study also shows the negative effects of an unusually thick snow cover. The impact can be measured by the proportion of yearlings in the population one year after winter. If the snow is exceptionally high, this increases the death rate, especially of the yearlings. [6]

Competition between chamois and tur: About half of all plants species eaten by the Caucasian Chamois also serve as food for the turs. Apparently the similarity of the food consumed by the two species acts as one of the principal causes of a certain antagonism between them; they are almost never found together in mountain pastures. In the Caucasian Nature Reserve, the number of chamois in the area is usually inversely proportional to the number of turs in the same places, and in many cases this cannot in any way be explained by the difference in the ecological requirements of the two species. It is extremely remarkable that on some mountain massifs, where many turs and few chamois now live, the ratio of their numbers was reversed 50 to 60 years ago. In areas where many turs occur, the chamois population generally does not experience any noticeable increase (Zarkow 1940, Nasimovic 1941, etc.). [77]

Food and feeding

The Caucasian Nature Reserve provides food consisting of over 100 species of plants. In May, the leaves of the herbaceous plants close to the roots are primarily bitten off in mountain pastures. In June, young shoots and leaves, as well as the unfolding inflorescences, are often eaten. In July, inflorescences and flower buds predominate in the forage, in August inflorescences and ovaries. In September the animals like to eat parts of plants that contain seeds. Thus, throughout the entire growing season, preference is given to the most nutritious parts of the plants (I. V. Zarkov).

In winter, grasses are eaten in large quantities, both dry and green. In the cold season and in early spring, thin branches, shoots and buds of deciduous trees – rowan (Sorbus), willow, beech and some others – also serve as an essential addition. Leaves and shoots of blackberries and mistletoe are often consumed (Nasimovic 1949). In winter, chamois also like to pluck pine and fir needles (Dinik 1910), casually eat the webs of hanging lichen Usnea barbata and sometimes tear moss from tree trunks (Nasimovic 1939). In forest areas they eat falling chestnuts and acorns in autumn (Markov 1938 and others). [77]

Breeding

rutting season: November into mid-December [5]

gestation: 165-175 days [10]

parturition: most kids are born in May-early June. A single offspring is usually born; twinning is rare. [10]

During the lambing season, cold-related setbacks are not uncommon, which is why many young animals die in the first few days of life. According to several years of observations in the Caucasian nature reserve, young make up an average of 17% of the number of all individuals encountered in June, but only 12% towards the end of the summer (Nasimovic 1949). According to Teplov (1938), more than 70% of the females that had young are without them by the end of July [77].

Activity pattern

Probably similar to Alpine Chamois. [10] In the Caucasus, they feed between 5:00 h and 11:00 h followed by a midday rest period. Foraging resumes at about 17 h. [10]

Status / population

The total population estimate for the entire Greater Caucasus is just over 9.000 individuals, and in general, the subspecies is still declining. [1]

The population size is approx. 6.000 mature individuals and there had been a decline by approx. 70 % since the 1960-1970s, which is suspected to continue. The subspecies is therefore assessed as VU C1. [1]

While Anderwald et al. (2021) write, that the outer limits of its distribution in the Greater Caucasus have not changed much during the last 50 years, except for the westernmost part, where it is no longer present [1], “Shackleton already wrote in 1997 that the “range in the Greater Caucasus is beginning to fragment all over.” [9]

In the Sakataly Nature Reserve from 1953-1957, herds over 40 were never seen (I. F. Popkova). In the first decades of the 20th century, however, herds numbering 100-200 were observed here, as in the territory of today’s Lagodekhi Nature Reserve (Markov 1938). [77]

In Russia, the total is ca. 5.500, with ca. 3.500 in the Western Greater Caucasus, up to 1.000 in the central part, and up to 1.000 in Chechnya and Dagestan (Reports on status of nature conservation in respective regions; Lukarevsky 2018; Yarovenko and Yarovenko 2018). Chamois numbers in Chechnya (mainly on the limestone Rocky Ridge; Lukarevsky 2018) probably amount to at least 300 animals, possibly more. Of all animals in Russia, ca. 1.200 occur in the Kavkazsky Biosphere Reserve (Trepet, 2018), 300 in Sochi NP (Semyonov and Voronin, 2018), ca. 200 in the Teberdinsky Biosphere Reserve (J. Tekeev, pers. comm.), and ca. 250 in the North Ossetinsky Nature Reserve, Tseysky Managed Nature Reserve and Alania National Park (Weinberg, 2018). [1]

The population history in Russia is as follows: 9.000 chamois on the northern slope in 1972, almost 6.000 of which inhabited Krasnodar Kray, and 1.200 in the Stavropol region (Ravkin, 1975). The population declined, and by the beginning of the 2000s, there were 1.500 in the Western Greater Caucasus (without Kavkazsky reserve), up to 1.300 in the Central Greater Caucasus, and more than 400 animals in Dagestan (Danilkin, 2005). In addition, there were about 1.000 Chamois in the Kavkazsky Biosphere Reserve (Trepet, 2014). [1]

In Georgia, combined aerial counts and ground censuses conducted during 2012-2014 produced a maximum number of 3.267 animals in the Greater Caucasus and 500-600 Chamois in Adjara in the Lesser Caucasus (Gurielidze 2015). This also represents a decline from an estimated 5.000 animals at the end of the 1980’s (Arabuli 1989). [1]

In Azerbaijan, only 600-800 individuals were left by the end of the 1990s compared to an estimate of 2.000-2.500 animals in the 1950-60s (Guliyev 2000). 341 animals were counted in the Zagatala Nature Reserve in 2015, and 315 in 2018; in Ilisu Nature Reserve, 24 and 18 animals, respectively, in the same years (A. Muradov, pers. comm.). No data are available from Shahdag National Park, the largest protected area in the Azerbaijan part of the Eastern Greater Caucasus. Chamois numbers probably decrease eastwards. [1]

Threats

The main threat for the subspecies is poaching. [1] The fact that the number of chamois in the Caucasus has declined sharply is also due to the species‘ conservative attitude towards its usual habitat. If turs are frequently disturbed by hunters and domestic livestock, they usually migrate to other mountain ranges, but the chamois remain in their traditional places, which ultimately leads to their destruction (Nasimovic 1941, Enukidze 1953). [77]

In some areas, competition with domestic livestock is a problem, and competition with Tur (Capra caucasica and Capra cylindricornis), Red Deer (Cervus elaphus), and Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus) is also possible. [1]

The scale of anthropogenic transformation of the Caucasian chamois population is shown based on the example of a local grouping of chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica, Lydekker 1910) from the Lagonaki Plateau (northwestern Caucasus). It has been established that the theoretical area of the range of the local chamois grouping under study is 58.000 ha and the fodder capacity is 45 individuals/1000 ha. The actual area of the range is currently approximately 20.000 ha, thereby having decreased by 66% over the last 100 years. At the present time, the density of the grouping does not exceed 5 individuals/1000 ha; i.e., it is nine times lower than it’s theoretically possible value. No positive dynamics of the population is observed, despite the nature reserve status of this area over the past 23 years. It has been concluded that the metapopulation structure of chamois is gradually simplified and the prospect of the long-term conservation of the species in the northwestern Caucasus is under threat. [2]

The adverse impact of humans on the chamois population is manifested in the regions with motor roads. The chamois, as compared to the deer, suffers from poachers to a lesser degree because it inhabits inaccessible areas and its trophy value is low. [6]

Conservation

In Azerbaijan R. r. caucasica is listed in the Red Data Book of Azerbaijan as a “species whose numbers declined in the past and are still low” (Guliyev 2013c). [1]

In Georgia it is also listed in the Red List of Georgia as Endangered (EN/A2a) (Decree 2014). In both countries, these listings exclude any extractive use, but do not lead to restrictions on land use or development projects affecting the species and its habitat (S. Michel, pers. comm.). [1]

In the Soviet Union, the chamois was considered rare, but was not included in Red Data Books. Later, it was still not listed in the Red List of the Russian Federation. Now there are plans to include the species in the new version of the Red List of Russia. [1]

Hunting

Hunting is legal in the Russian Federation and Azerbaijan. It is presently not allowed in Georgia. In the Russian Federation, hunting of Caucasian Chamois is permitted in Kabardin-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia and North Ossetia-Alania, but is is largely incidental and usually connected with tur hunts. The season runs from August through November. In other Russian territories this subspecies is listed in the regional Red Data Books. The annual legal harvest in only around 15 individuals (Lomanova 2010). [5]

Ecotourism

Most likely negligible. Only 40 observations are recorded on inaturalist for the entire Greater Caucasus (as of 2024-04-17).

Literature cited

[1] Anderwald, P., Ambarli, H., Avramov, S., Ciach, M., Corlatti, L., Farkas, A., Jovanovic, M., Papaioannou, H., Peters, W., Sarasa, M., Šprem, N., Weinberg, P. & Willisch, C. 2021. Rupicapra rupicapra (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T39255A195863093.https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39255A195863093.en. Accessed on 23 January 2023.

[2] Sthgey A. Trepet, T. G. Eskina, K. V. Bibina, 2017: Anthropogenic Transformation and Prospects for Conservation of the Chamois Population (Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica) in the Northwestern Caucasus. Biology Bulletin 44 (9): 1166-1173

[3] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[4] Couturier, Marcel A. J., 1938: Le Chamois Rupicapra rupicapra (L.). B. Arthaud (editor), Grenoble. En vente chez l’auteur.

[5] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[6] Sthgey A. Trepet and T. G. Eskina, 2013: The influence of environmental factors on the dynamics of the size and spatial structure of the chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica) population on the Caucasian Reserve. Biology Bulletin 40(8)

[7] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[77] Heptner, V. G. and Naumov, N. P. (edit.), 1966: Die Säugetiere der Sovjetunion. VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena

[8] Lovari, S. and Scala, C., 1984: Revision of Rupicapra Genus: IV: Horn biometrics of Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica and its relevance to the taxonomic position of Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica. Z. f. Säugetierkunde, 49 (4): 246-253

[9] Shackleton, D. M (ed.) and the IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 1997: Wild Sheep and Goats and their Relatives. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 390 + vii pp

[10] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.