The Anatolian Chamois is a very rarely discussed and documented taxon. Lydekker described it for the first time in 1908. Find below a summary of facts and some rare photographs.

If you want to know how an Anatolian Chamois looks like, you have a hard time to find something decent. There are only a few published illustrated accounts on Anatolian Chamois. In the „Handbook of the mammals of the world“ Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) present a drawing of a specimen only in winter pelage. In the „CIC Caprinae Atlas of the world“ Damm and Franco (2014) show a single photo taken at the end of winter under foggy conditions. In „Bovids of the world“ José R. Castelló (2016) leaves a blank in the respective chapter on page 424.

I got in contact with Prof. Ahmet Karataş, who sent me some exceptional photographs showing Anatolian Chamois in summer pelage. I have the honour to present them on caprinae world. Eventually I visited the populations in the Munzur and Kaçkar Mountains myself in 2023.

Names

English: Anatolian Chamois, Turkish Chamois [2, 3], Asia Minor Chamois [2, 16]

French: Chamois d’Anatolie [2, 3]

Georgian: archvi, psiti [3]

German: Anatolische Gämse [2], Türkische Gämse [7], Kleinasien-Gämse [16]

Russian: Анатолийская серна, или турецкая серна [Wikipedia, Russia]

Spanish: Rebeco de Anatolia [2, 3], gamuza turca [2], Rebeco de Asia Menor [16]

Turkish: cengel boynuzlu, dag kecisi, samua

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms:

Rupicapra tragus asiatica [16]

Rupicapra asiatica [16]

Rupicapra asiatica asiatica [2]

Rupicapra asiatica asiatica [2]

Taxonomy

While some authors [3] see the Anatolian Chamois as a subspecies of the Alpine Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra), others like Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) see it – together with the Caucasian Chamois – as a distinct species Rupicapra asiatica.

Groves and Grubb (2011) write: „On geographic grounds, it does seem probable that R. asiatica, the chamois of Turkey and the Caucasus, is distinct from others, but more evidence is needed. [4]

Scala and Lovari (1984) compared the horn biometrics of 13 male adult Turkish Chamois with a sample of 12 adult male Caucasian Chamois. No variable proved significantly different. Thus, horn biometrics do not allow the separation of these taxa in distinct subspecies, supporting Camerano’s and Kumerloeve’s suggestion that caucasica should be grouped with asiatica. [5]

Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica, Lydekker, 1908, Trebizond (modern day Trabzon [Wikipedia]), Asia Minor, Turkey [16]

Diploid chromosome number: 2n = 58 [3, 16]

Distribution

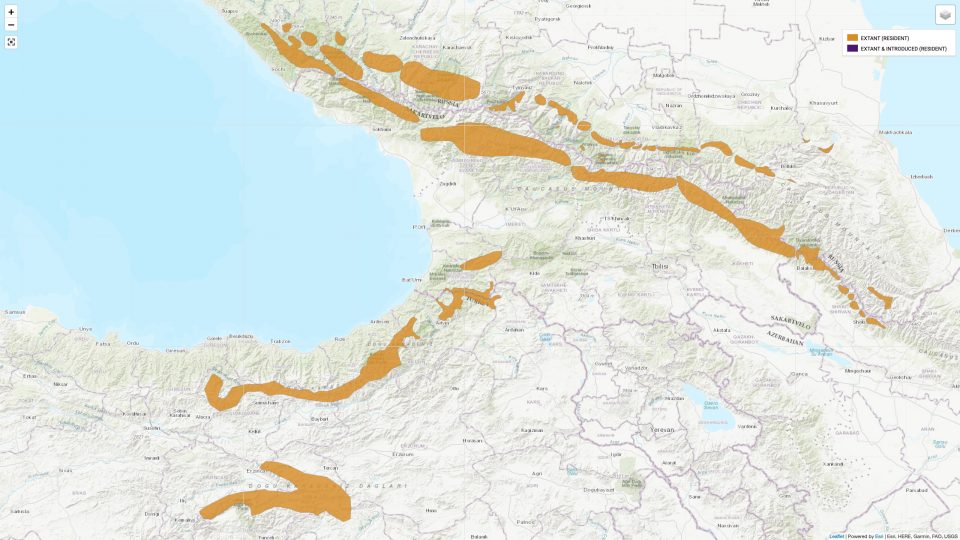

According to IUCN the subspecies R. r. asiatica only occurs in the northeastern mountains of Turkey and the southwestern regions of Georgia in three mostly isolated populations (the IUCN map below shows actually FOUR subpopulations).

The four subpopulations of the Anatolian Chamois (four areas below). Because of the complex topography in the region it is difficult to designate the various areas with a single name: The northernmost subpopulation of the Anatolian Chamois is within the Meskheti Range including Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park in Georgia. (Interestingly the IUCN does not mention Borjomi-Kharagauli National Park itself as part of the distribution area, although chamois is there.) To the south follows the Georgia-Turkey border subpopulation in the region of the Karçal Mountains (see also next paragraph). The long spine parallel to the Black Sea is part of the Pontic Mountain system including Kaçkar Mountain. A main part of the southernmost distribution area is the Munzur Mountains.

The Karçal Mountains or Karaçal Mountain (Georgian: კარჩხალი; pronounced „k’archh’ali“) is a mountain range located in the northeastern tip of Turkey, within the borders of Artvin province. Karchal has been changed from Georgian „Karchali“ and Karchali (კარჩხალი) meaning „bare mountain“, „rocky mountain“. These mountains extend to the Georgian border with the Coruh and Berta valleys. The highest point is at 3.428 meters. The Karçal Mountains, where glaciers and glacial lakes are located, are especially popular with hikers. [Turkish Wikipedia]

The Kaçkar Mountains and the transboundary populations between Turkey and Georgia have not been connected since 2000 due to the building of a large dam in the province of Artvin. There is also increasing highway constructions and decreasing population sizes. Therefore the Kaçkar Mountain and the eastern Anatolian populations have become isolated. There is no evidence that they are connected any longer. [1]

Heptner, V. G. and Naumov, N. P. (1966) also name the Taurus Mountains as a distribution area of the Anatolian chamois, in particular the Cilician Taurus, the Antitaurus and the Armenian Taurus, as well as the area southeast of Lake Van [77], areas that don’t show up on the IUCN-chamois distribution map anymore.

Previous distribution maps by Turan (1984) and Lovari and Scala (1984) also show a wide coverage in eastern and northeastern Anatolia including Mount Ağrı and Cilo, but recent studies have indicated that Anatolian Chamois have been disappearing from many of the former habitats (Ambarlı 2014). [1]

Description

The Asian Minor Chamois – including the Anatolian Chamois – is smaller in size than the Alpine Chamois.

Note: There is no subspecies-specific information about the R. r. asiatica population in Georgia. Georgian scientists do not distinguish between asiatica and caucasica. [3]

head-body (males): 125-135 cm [16]; (females): c. 96 cm [16]

shoulder height: 78-86 cm [16]; 75 cm [3 – without citation]

weight: less than 40 kg [3 – without citation]

weight males: 30-50 kg [16]

weight females: 25-42 kg [16]

scull length: On the scull the nasals exhibit a strongly marked lachrymal process and a large and persistent lachrymal fissure. [3 – quoting Lydekker 1913]

tail: c. 8-10 cm [16]

Colouration / pelage

It is similar in body colouration to Alpine Chamois (R. Rupicapra). [16]

general colour in winter: dark brown to black. [3]

summer pelage colour: Damm and Franco (2014) write that it is „brown with a darkish dorsal stripe“. To be more precisely, the colour of the chamois – including the Anatolian Chamois – is „chamois“, which is a yellowish-brown.

neck and legs (winter): blackish-brown, usually darker than in the Alpine race [3]

underparts: pale [3]

rump patch: white [3]

head: throat, lower jaw, and front of face yellowish-white; dark stripes across the eyes to the muzzle [3]. According to Lydekker (1913) the light area of the face is relatively small, with the frontal portion dull chestnut. [3] In Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) the illustrator for plate 48, page 740 depicted an Asian Minor Chamois in winter pelage and did the above description justice by omitting a light-coloured throat patch.

immature animals: According to Damm and Franco (2014) the general colour is light brown, with a narrow and distinct dorsal stripe [3], however in the photo presented below (taken: 2019-08-04) the depicted young is considerably darker than its mother – as is the case in other chamois subspecies.

Horns

According to Lydekker (1913) the horns are relatively short and thin, of little extension and generally not as heavy and long as in some of the other chamois subspecies. [3]

Lovari and Scala (1984) compared the horn biometrics of 13 male and 10 female adult Turkish Chamois to assess sexual dimorphism. Out of 9 different measures, only the transverse and antero-posterior diametres at horn base proved significantly greater in males, the males bearing stouter horns than females. On the whole, R. r. asiatica shows shorter horns than all other chamois subspecies, but for parva, pyrenaica and caucasica. [5]

horn length max.: 27,0 cm (male; n=13); 21,5 cm (female; n=10) [5]; horns over 25,4 cm do occur, but are rare [3];

horn length mean: 22,9 cm (n=67; from SCI and RW listings) [3]

horn length males mean: 22,346 cm (n=13) [5]; 19,7 (n=3) [4]

horn length females mean: 19,01 (n=10) [5]; 18,0 (n=1) [4]

horn basal circumference mean: 8,9 cm (n=67; from SCI and RW listings) [3]

antero-posterior diameter at base male mean: 2,731 cm (n=13) [5]

transverse diameter at base male mean: 2,454 cm (n=13) [5]

antero-posterior diameter at base female mean: 2,34 cm (n=10) [5]

transverse diameter at base female mean: 1,98 cm (n=10) [5]

distance between tips, males mean: 7,208 cm (n=13) [5]; 5,95 cm (n=2) [4]

distance between tips, females mean: 7,85 cm (n=10) [5]; 7,5 cm (n=1) [4]

minimum distance between horn bases male mean: 1,162 cm (n=13) [5]

minimum distance between horn bases female mean: 1,08 cm (n=10) [5]

Trophy hunters in Turkey are said to sometimes be more interested in killing females “due to their longer horns compared to males”. [1] For the Anatolian Chamois it seems conceivable that overhunting has wiped out most of the older males, leaving only younger males or those with smaller horns.

Horn length measurements for Alpine Chamois presented by Damm and Franco (2014) indicate an interesting pattern, that could be principally true for other subspecies of chamois as well and should also be considered in the Anatolian Chamois: While the mean length is 1 cm longer in males (26 cm : 25 cm in females), the mean height is 1 cm longer in females (18 cm : 17 cm in males). [11]

Habitat

Asia Minor Chamois occur at elevations of 200-2850 metres [16]. (The highest peak within the distribution area is Kaçkar Dağı at an elevation of 3.937 metres.)

Predators / Mortality

Wolves (Canis lupus) and Eurasian Lynx (Lynx lynx) are major predators. Domestic dogs can be major predators in some areas. [16] At Kaçkar Dağı the leopard is known to occur.

Food and feeding

feeds principally on forbs and graminoids during summer and on browse during winter. [16]

Breeding

rutting season (Asia Minor Chamois): late October to early December [16]

gestation: 165-175 days [16]

parturition: late April to mid-June; most kids are born in May-early June. A single offspring is usually born; twinning is rare. [16]

Activity pattern

probably similar to Alpine Chamois [16]

Status / population

About 600 Anatolian chamois inhabit the mountainous areas of north-eastern Turkey, and another 200 are estimated to live in Georgia. [17]

Others estimate the total population size between 500 and 750, with a total extent of occurrence (EOO) over 9.000 km2, but a very low area of occupancy (AOO). Group sizes in the Kaçkar Mountains have decreased significantly from 40 to 50 individuals in the 1990s to a maximum of 25 individuals (but mostly only 3 to 7) between 2006 and 2012 during mating time observations (Ambarlı 2014). Along with the disappearance from former habitats and increasing habitat fragmentation, the population size of Anatolian Chamois has decreased sharply in the last three decades (by ca. 60-70 per cent, with the greatest reductions in population, AOO and EOO probably occurring between 1980 and 2000; Ambarlı 2014). [1]

Recent data suggest that the subspecies has experienced catastrophic declines in population size in the last several decades due to intensive human impact. The overall population is less than 2.500 mature individuals (estimated between 500 and 750 individuals). There is an observed and projected decline by more than 20 per cent in two generations based on recent, ongoing and planned development projects (roads and hydro-power plants in montane areas) affecting habitat and connectivity, and causing an increase in pressure by illegal hunting. Therefore, the subspecies asiatica should be listed as Endangered (EN) C1+2a(i). [1]

Threats

The main threats are poaching, trophy hunting (see chapter “hunting”), habitat degradation and isolation due to the construction of new roads to alpine habitats for mass tourism (Ambarlı 2014). [1]

Additional threats include the construction of hydro-electric power plants above 2000 meters, increasing tourism activities, heli-skiing causing avalanches and disturbing the animals during pregnancy, and chasing individuals by using unmanned aerial vehicles in refuge areas. [1]

Alpine tourism and new road constructions in the Kaçkar Mountains for the “Green Belt Roads“ Project by the Ministry of Tourism has caused catastrophic destruction of the prime habitats of Anatolian chamois. Additionally, interspecific competition with wild goats and livestock has probably pushed chamois up to higher altitudes and restricted the subspecies’ range in the alpine zone to mostly above 2.000 m. [1]

Conservation

The Anatolian Chamois has so far been the only subspecies categorized as DD (data deficient). [1] HoweverAmbarli (2015) suggests to change to EN (endangered). [18] There is only a limited number of studies about the species in Turkey. [1]

To protect chamois and stop the population decline in the 1990s, five wildlife reserves were established, but they have no viable populations any longer. Both the number of game wardens and conservation efforts in high mountain areas are inadequate, and limited resources are allocated to monitoring efforts and law enforcement. [1]

Hunting

The Anatolian Chamois has been fully protected by the Land Hunting Law 4915 since 2003 (Official Gazette of Turkish Republic 2003). However, there has been constant trophy hunting since 1989. The illegal hunting fee is about 5.000 Euro. [18] Also poaching still continues mainly on the population of the northeastern Black Sea Region and transboundary populations. [1]

Hunting regulations were changed in 2010, and the ban on killing females during trophy hunting was lifted because hunters had complained about difficulties in correctly sexing individuals from a distance. Moreover, trophy hunters are sometimes more interested in killing females due to their longer horns compared to males. As a result of the new hunting regulations, and because trophy hunting mostly takes place during the rut and birth seasons, both reproductive success and birth rates have likely also decreased. Additionally, the number of quotas is not determined based on robust scientific data. Instead, most are given out over the desk or by relying on hunters’ observations without knowledge of actual population sizes in wildlife reserves. [1]

To stop further decline it is suggested to stop trophy hunting until reliable population censuses are made. Furthermore the killing of females during trophy hunts must be stopped. [18]

Ecotourism

most likely negligible; only one report available on mammalwatching.com (as of 2023-01)

Literature cited

[18] Ambarli, Hüseyin, 2015: Status and Management of Anatolian Chamois (Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica): Implications for Conservation. In: Antonucci A. & Di Domenico (eds.). 2015. Chamois international Congress Proceedings. 17-19 June 2014, Lama dei Peligni, Majella National Park, Italy, 272 pages.

[1] Anderwald, P., Ambarli, H., Avramov, S., Ciach, M., Corlatti, L., Farkas, A., Jovanovic, M., Papaioannou, H., Peters, W., Sarasa, M., Šprem, N., Weinberg, P. & Willisch, C. 2021.Rupicapra rupicapra (amended version of 2020 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T39255A195863093.https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39255A195863093.en. Downloaded on 11 October 2021.

[2] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[17] Corlatti, Luca and Zachos, Frank (Editors), 2021: Northern chamois Rupicapra rupicapra (Linnaeus, 1758) and Southern chamois Rupicapra pyrenaica Bonaparte, 1845. In: Handbook of the Mammals of Europe – Terrestrial Cetartiodactyla. Publisher: Springer Nature.

[3] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[77] Heptner, V. G. and Naumov, N. P. (edit.), 1966: Die Säugetiere der Sovjetunion. VEB Gustav Fischer Verlag, Jena

[5] Lovari, S. and Scala, C., 1984: Revision of Rupicapra Genus: IV: Horn biometrics of Rupicapra rupicapra asiatica and its relevance to the taxonomic position of Rupicapra rupicapra caucasica. Z. f. Säugetierkunde, 49 (4): 246-253

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[11] Salm, Urs Peter und Schnidrig-Petrig, Reinhard: Die Gemse – Biologie und Jagd, 2009. Salm Verlag, Bern

[12] Shackleton, D. M (ed.) and the IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 1997: Wild Sheep and Goats and their Relatives. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 390 + vii pp

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.