The Cyprus Mouflon is endemic to the Mediterranean island of Cyprus and an example of island dwarfism. (9) Shoulder heights measure on average 15 centimeter less than in the Armenian Mouflon. (10) On the other hand the Cyprus Mouflon is the largest wild land mammal on the island. It has become the national animal of the country. (2)

As the national animal, the Cyprus Mouflon is eternalized on different cent coins.

Names

English: Cyprus Mouflon, Cyprian Mouflon

French: Mouflon de Chypre

German: Zypern-Mufflon

Greek: Agriopovato, Kypriakó agrinó

Italian: Muflone di Cipro

Russian: Кипр муфлон

Spanish: Mouflon de Chipre

Turkish: Yaban Kıbrıs

Other Names and Synonyms

Ovis musimon var. orientalis; Brandt and Ratzeburg 1827; Ovis orientalis [gmelini, musimon] ophion, Blyth 1841; Ovis cypris, Blasius 1857; Ovis gemelinii musimon var. ophion (Cyprus), Cugnasse 1994 (1); Ovis aries (5)

Taxonomy

Ovis gmelini ophion (Blyth, 1841)

Type locality: Cyprus

Many authorities state that the Cyprus Mouflon is a feral descendant (5) of semi-domesticated sheep translocated by humans during the Neolithic. Therefore the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (BZN 2003) prescribes the scientific name Ovis aries ophion. (1) However recent findings suggest that the Cyprus Mouflon is strongly diverged from western Mediterranean conspecifics, while Northwest Iran appeared as the most credited geographic region as the source for its ancient introduction to Cyprus. (2) Additionally, a close phylogenetic relationship between the Cyprian and the Anatolian Mouflon was detected. (6) Therefore it is suggested to use the name Ovis gmelini ophion. (2, 6)

The emergence of a dwarf

The Cyprus Mouflon was probably introduced onto the island about 8.000 years ago. Ovis bones were found at the Neolithic village of Khirokitia. Modern and ancient mouflon seem to correlate – except for their size. Modern Cyprus Mouflon are about 18 prozent smaller. (1) It is thought that this diminuation is an example of island dwarfing. Reasons that could lead towards island dwarfism are: poor forage conditions, possible phosphorus shortage, limited living space and the forested mountainous habitat and limited predation. But becoming smaller might be disadvantageous, when predators are around. So it is thought, that island dwarfism of large mammals on islands arises only in the absence of predation.

Distribution

Cyprus. In the Middle Ages, the mouflon was plentiful in nearly all parts of this mediterranean island. (8) Today the home of the Cyprus Mouflon is the mountainous Paphos Forest and adjacend areas including parts of Trodoos National Forest. (2) During the last decade the mouflon has expanded its range eastward. It’s current geographical coverage of the island exceeds 700 km2. (4)

As grazers forests are not a preferred habitat for mouflons. But on Cyprus the only other option for them is agricultural land adjacent to wooded areas.

General discription

total length: no data avaiable

mean shoulder height: 68 cm (males) (1)

tail length: no data avaiable

weight (mean): 36 kg (males); 23,9 kg (females) (3); maximum: 41,5 kg (male), 30 kg (female) (1)

horn length: 50-65 cm (males); ewes are hornless; the longest horn length in Rowland Ward meassures 71,1 cm (1);

life expectancy in the wild: no data avaiable

diploid chromosome number : 54 (1)

Colouration

In general the pelage is reddish-brown. Some parts are or can be white or whitish: underparts, a small portion of the rump, muzzle, throat, the area around the eyes and parts of the legs. Males can show a white saddle patch – indistinct during the summer, prominent during the mating season – growing with age. Some body parts show black markings: in females generally only the front side of the upper front legs and the upper side of the tail. Males can show black markings on lower throat, neck, back, breast, legs, on the upper side of the tale and as black flank stripes. During the mating season the black extends from the back to the sides and enframes the white saddle patch on the front side. Rams become darker with age. The face appears greyish.

The age of females can be estimated based on the size of the face mask. Lambs and yearlings have no face mask. The first sign of which appears on the tip of the nose near the age of two year (12).

Horns

The Cyprian Mouflon ram has sickle-shaped, yellowish-brown horns curved in one plane. These horns either curve back behind the head toward the neck, with tips directed at the sides of the neck (cervical) or above the neck (supracervical). In older males the horn tips often terminate only a few centimeters apart. Horns show three sides with a good fronto-nuchal edge and the fronto-orbital edge almost completely rounded off. (1) All females are hornless. (Hadjisterkotis 2016, pers. comm.)

Horns of Cyprus Mouflon show three sides: orbital surface (white), frontal surface (red), nuchal surface (green). The fronto-nuchal edge (where red and green merges) is sharp. The fronto-orbital edge (where white and red merges) is almost completely rounded off.

Quartet of four moufloniforms: Cyprus Mouflon (Ovis gmelini ophion) – up left; introduced European Mouflon (Ovis aries musimon) – up right.; Armenian Mouflon (Ovis gmelini gmelinii) – bottom left; Bukhara Urial (Ovis vignei bocharensis) – bottom right. Traditionally Cyprus and „European“ Mouflon were believed to be closely related. Latest findings see Cyprus and Armenian Mouflon as one species. Furthermore the Bukhara Urial is a different species again, but can show the supracervical horns like Cyprus and Armenian Mouflons. Photo of Cyprus Mouflon: E. Hadjisterkotis; others: R. Bürglin

Habitat

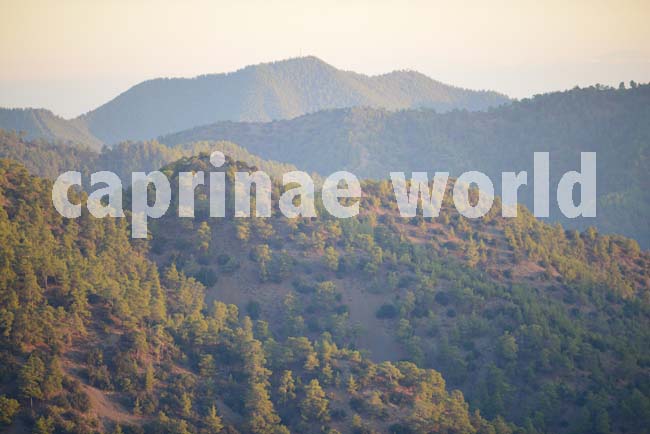

The mouflon habitat in present times lies within mountainous, wooded terrain. Some parts border on agricultural land. (3) The forested part is covered with pine (Pinus brutia), Golden oak (Quercus alnifolia), further with Cyprus Cedar (Cedrus brevifolia), Greek Strawberry Tree (Arbutus andrachne) and Plane trees (Platanus orientalis). (1)

Predominating trees species of the Paphos Forest are pine (Pinus brutia) and Golden Oak (Quercus alnifolia) (11)

Mortality

disease-related: 30 %; predators: 25 %; poaching: 16 %; collisions with vehicles: 13 %; the rest being accidents, snake-bites and unknown. (4) The highest mortality is during the rut. Due to the stress of the rutting season, poor nutrition in late summer and autumn, old age, diseases, and cold weather, many rams do not recover from nutritional deficiences and die. Mouflon have a wide range of diseases and bone lesions. The most important defect being spondylosis. (3)

Predators

Feral dogs and foxes. (4) Although foxes are the major scavenger of dead mouflon, there are no direct observations of foxes killing adult mouflon. There are observations of foxes following mouflon from safe distance, as well as a report of a ram fatally injuring a fox. There is two cases reported where foxes were observed killing juvenile mouflon away from cliffs. More direct killings are reported by stray dogs than foxes. (7)

The Cyprus Fox (Vulpes vulpes indutus) is probably not a significant predator, though preying on lambs is documented.

Food and feeding

The main item in the diet consists of forbs and grasses with a greater variety of woody browse and fruit in the diet of forest dwelling animals (compared to animals which live at the edge of the forest, which supplement their diet with agricultural plants). (3, 11) Cyprus Mouflon feed on more forbs and grasses than Euopean Mouflon. (11)

During the summer grass in the forest is gone. The animals may start to starve. The abundant Golden Oak (Quercus alnifolia) doesn’t provide a remedy …

… their leaves are basically deadly for mouflons. The ingredients destroy the bacteria in the rumen, on which they depend.

In a study eighty-five forage species were determined. Usually by June all grasses are dry, and forage is reduced in quantity and quality. As pasture forage matures, the protein content declines, fibre increases, and both forage intake and digestibility decline. In fact the quality of grass, which is the most important item in the diet of the Cyprus Mouflon, declines drastically in the course of the seasons. By late summer and early fall respectively the quality falls below the minimum requirements for maintenance. As a consequence the animals starve. Depending on the rains fresh grass might not appear before November or December. (3) In fall and winter mouflon feed on fruit, which can be a considerable item. In spring a larger quantity of tree leaves are eaten, particularly in April when the are just sprouting. (11)

Breeding

Sexual maturity reached: In a study no yearlings were observed giving birth or being followed by a lamb. Other populations of wild sheep are known to mature sexually earlier than free-ranging Cyprus Mouflon. This is for example the case for Corsican Mouflon, where a small percentage conceives as yearlings. (12)

Mating: end of october to early november (14)

Gestation: about 5 month (10)

Parturition: middle of April (10); from end of march to the end of may, with the majority of births taking place in the first 20 days of April. The lambing season is considered short characteristic of animals living in a harsh environment. (12)

Young per birth: 1-2 (3)

Movements, home range

There is a tendency for rams to separate during lambing from the ewes and their young. The sexes rejoin in one unstable group during autumn for mating. (12)

During spring females move to areas with sharp cliffs (e.g. Limnitis valley) which provide refuge for lambing. Lack of water combined with lack of forage is driving mouflon outside the forest. (14)

Social organisation

Herd social structure is similar to other wild sheep species where same-gender groups are seperated all year except from the rut. Cyprus Mouflon exhibit smaller group size (mean = 2.9 individuals) compared to other species inhabiting more open habitats. (4)

Conservation: threats /measures

IUCN does not classifiy the Cyprus Mouflon as a wild species. Hence the species is not further mentioned in the red list. (5)

During its history the Cyprus Mouflon has repeatedly been reduced to very small numbers. (9) Uncontrolled hunting and habitat destruction almost drove this endemic Cyprian mammal to extinction. At the beginning of the 20th century, the population had been reduced to a few dozen.

Conservation efforts in recent years have saved it and there is now over 3.000 individuals (4), mainly in the Paphos Forest area.

Today poaching, habitat degradation and loss (also through forest fires), road building and livestock intrusion (risk of pathogen infection; increased presence of feral dogs) represent the main threatening factors. (2,4) In 1997 it was shown that small game hunting has a negative effect on mouflon through disturbance (increased energy demand during times of poor nourishment conditions; movement to less suitable habitat) and increased opportunity for poaching. (13) Furthermore lack of water because of climate change and draining springs for irrigation was also found as threatening factor. The illegal introduction of wild boar through hunters implies competition for the mouflon. (14)

Fall counts are carried out each year since 1997. (4)

It was shown recently that forensic wildlife investigations help to tackle illegal mouflon killing. Police and ‚Game and Fauna Service‘ had confiscated samples (meat, hairs, bloodstains). Through mitochondrial and DNA markers the species-specific affiliation could be determined. (2)

Trophy hunting

In the Middle Ages, the mouflon was plentiful in nearly all parts of Cyprus and was hunted by the aristocracy using hounds and coursing them with cheetahs. (8) No offical hunting takes place today.

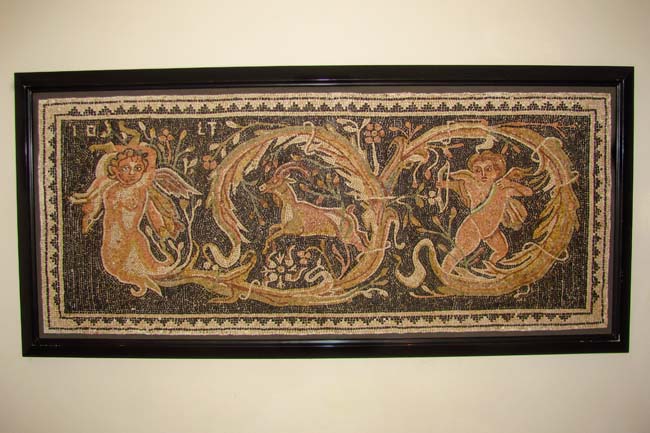

Mosaic of a hunting scene at Kykkos monastery. Presumably depicting a moufflon, 4th to 5th century AD.

Ecotourism

The mouflon enclosure at Pavros tis Psokas has some touristic significance. But there are no wildlife-watching-companies offering tours to watch wild Cyprus Mouflon. There are also no trip reports available in the internet of people, who have actively searched for wild Cyprus Mouflon (such trip reports could be seen as an indicator for the importance of the species as an antractor). In birdwatching trip reports the species is mentioned occasionally. Given the vast number of nature lovers coming to Cyprus (98 birding trip reports at avibase – 2016/09) and given the relativ openess of the habitat, which makes wildlife watching relatively easy, it is astonishing that the mouflon does not draw more attention. My own report you find here.

Literature Cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Coucil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Guerrini, M.; Forcina, G.; Panayides, P.; Anayiotos, P.; Kassinis, N., Garel, M.; Lorenzini, R.; Hadjigerou, P.; Barbanera, F.: Population genetics and forensic DNA for conservation management of the Cypriot Mouflon (Ovis orientalis ophion). In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) pages 34-35, Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(3) Hadjisterkotis, Eleftherios: Population, Ecology and Food Habits of the Cyprus Mouflon. In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) page 37, Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(4) Kassinis, N.; Ioannou, I., Panagides, P.; Mammides, C.; Nicolaou, K.: Current Status, Population Dynamics and Causes of Mortality in Cyprus Mouflon. In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) pages 41. Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(5) Valdez, R. 2008. Ovis orientalis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15739A5076068. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15739A5076068.en. Downloaded on 21 September 2016.

(6) Mereu, P.; Pirastru, M.; Barbato, M.; Hadjisterkotis, E.; Leoni, GG.; Naitana, S.; Masala, B.; Manca, L.: The entire mtDNA Sequence of the Cyprus Mouflon (Ovis gmelini ophion) – a new Method for the Study of Mouflon and Domestic Sheep Evolution. In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) pages 48-49, Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(7) Constantinou, G.; Hadjisterkotis, E.: Fox Predation on Cyprian Mouflon and Marine Turtles on Cyprus. In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) pages 68-69, Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(8) Nicolaou, H.; Hadjisterkotis, E.; Papasavvas, K.: Past and Present Distribution and Abundance of the Cyprus Mouflon. In: E. Hadjisterkotis (ed.) page 90, Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus

(9) Hoefs, M. and Hadjisterkotis, E.: Horn Characteristics of the Cyprus Mouflon. In: Abstracts – 6th World Congress on Mountain Ungulates and 5th International Symposium on Mouflon. August 29th-September 1st, 2016, Nicosia, Cyprus

(10) file:///Users/ralf/Documents/Eigene%20Dateien/Buch-:Artikel-Projekte/Cervidae%20:%20Caprinae/Caprinae/Infos%20zu%20Caprinae-Arten/Ovis/Zypern-Muflon/Zypern-Mufflon.webarchive

(11) Hadjisterkotis, E., 1996: Ernährungsgewohnheiten des Zyprischen Mufflons Ovis gmelini ophion. Z. Jagdwiss. 42 (1996), 256-263

(12) Hadjisterkotis, E. and Bider, J. R., 1993: Reproduction of Cyprus Mouflon (Ovis gemelini ophion) in captivity and in the wild. Int. Zoo Yb. (1993) 32: 125-131 – The Zoological Society of London.

(13) Hadjisterkotis, E. and van Haaften, J. L., 1997: Die Niederwildjagd im Wald von Pathos und ihre Auswirkungen auf das gefährdete zyprische Mufflon Ovis gemelini ophion. Z. Jagdwiss. 43 (1997), 279-282

(14) Hadjisterkotis, E., 2001: The Cyprus mouflon, a threatened species in a biodiversity „hotspot“ area. Pages 71-81, In Nahlik A. and Walter Uloth (eds.), Proceedings of the International Mouflon Symposium, Sopron, Hungary.