The Golden Takin has the most spectacular pelage colour of all four Takin subspecies. It is the neighbour of the Sichuan Takin to the east.

Names

Chinese: líng niú shăn xī yà zhŏng [2]

English: Golden Takin, Shaanxi Takin [2]

French: Takin doré [16], Takin d‘ Or [2]

German: Gold-Takin [2], Goldtakin [16]

Spanish: Takin dorado [2, 16]

Tibetan: Ri-ka, Ye-more [2]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

none known [2]

Taxonomy

Budorcas taxicolor bedfordi Thomas, 1911, Tai-pei Shan, South Shaanxi, China

Some authors see the Golden Takin as a full species (Budorcas bedfordi) [1, 4, 16], others prefer to separate it as a subspecies (Budorcas taxicolor bedfordi) [2, 6, 10, 13]. Distinctions of the four phenotypes are mainly based on different coat colours and distribution ranges.

diploid chromosome number: 52 [2]

Similar subspecies

The Golden Takin has a brighter pelage colour compared to the Sichuan Takin. [1] Descriptions of the body sizes are not consistent: Damm and Franco (2014) state that Golden and Bhutan are smaller than the Sichuan Takin. Matschei (2012) writes that Golden and Sichuan Takin are bigger than the Mishmi Takin. Castelló (2016) notes that the Golden Takin is slightly smaller than the Sichuan Takin. Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) do not see any differences in body sizes.

Distribution

by country / state: China / Shaanxi (south) [16].

The Golden Takin is confined to the Qinling Mountains (Qin Mountains [2]) in southern Shaanxi, Central China [6], which extend from west to east for 300 kilometres. [2]

Damm and Franco (2014) quote Lydekker (1913), who mentions that the distribution range also reaches Gansu province. The westernmost tip of the Qinling Mountains just lies within that province. It is not clear if the Golden Takin still occurs there today.

The current distribution region in Shaanxi covers 18 counties: Foping, Yangxian, Ningqiang, Liuba, Mianxian, Chenggu, Ningshan, Shiquan, Fengxian, Zashui, Zhen’an, Danfeng, Taibai, Meixian, Zhouzhi, Liantian, Chang’an, and Huxian (Forestry Bureau of Shaanxi Province, 2001). [6]

Three centres of relatively high population density occur in Taibai, Ningshan and Zhouzhi, where they are restricted to the upper catchments areas of several rivers (Wu et al. 1987). [12]

Description

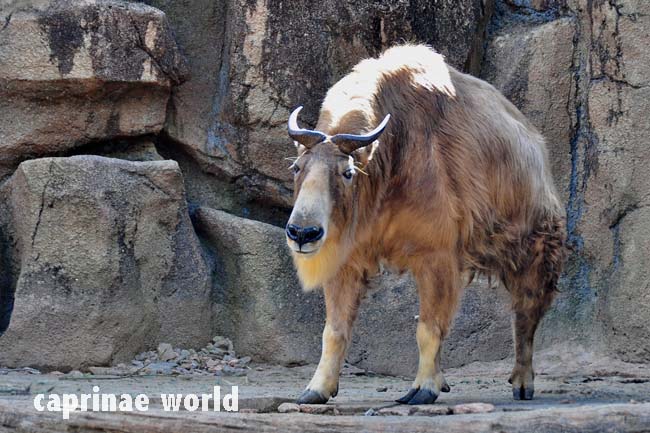

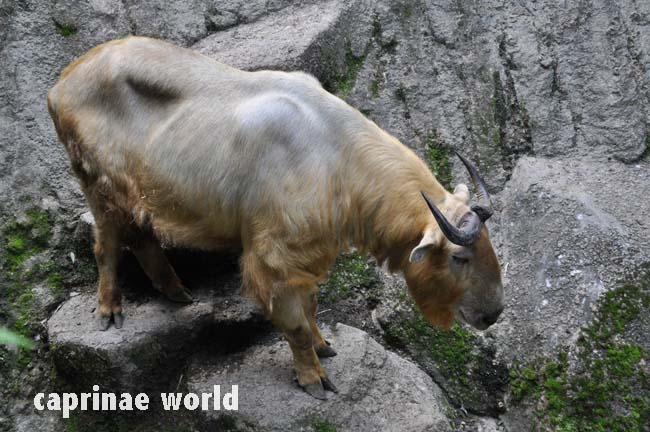

Takins in general have large, bovine-like bodies, a shaggy coat including long hair on the side and under the jaws, stout legs, prominent dew claws, and are taller at the shoulder than the hip. [16]

Otherwise descriptions of relative body sizes are rather contradicting (see „Similar subspecies“)

The following measurements of Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) probably refer to Takins in general [16]:

body length: 170-220 cm – males are significantly larger than females [13, 16]

shoulder height: 107-140 cm [13, 16]; 130-140 cm [2]

weight: 150-350 kg [16], 250-600 kg [13]; in adult males it may exceed 350 kg, adult females weigh around 250 kg. [2]

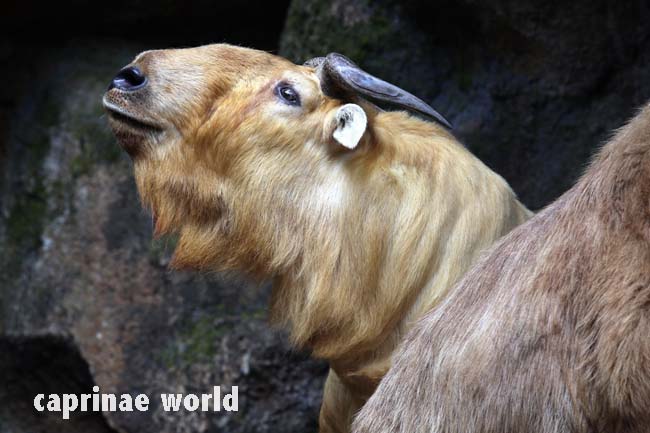

Colouration / pelage

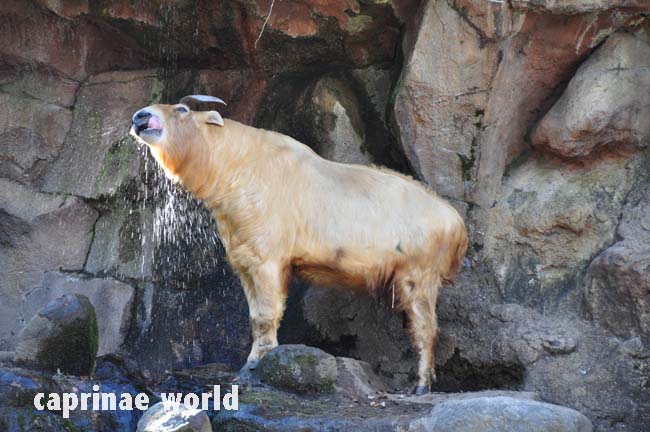

Like sizes general descriptions of pelages are not consistent. Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) write that adult male body pelage is creamy white to golden yellow with distinctly golden hair on the neck and chest of adult males. They also write that Golden Takins usually have black hairs on muzzle, knees, hock, and tail. [16] Damm and Franco (2014) state the general pelage colouration is a golden buff, tending to ocherish in males and creamy in females, with the face being similar in colour and black hair only at the tip of the muzzle. In old males the colouration may deepen to a reddish-yellow with golden hairs on the neck and fore-chest. [2] The authors do not distinguish between summer and winter coat or breeding season and non breeding season respectively.

Animals from Gansu province are said to be more brownish-orange (Lydekker 1913) [2]

summer coat: rich golden yellow [2, 13]

Golden Takin couple in June (female in the back). Pelage colour of the female is a golden brown. Photo: Yasuki Ichishima, Tama, 2017-06-03

Golden Takin male in September (after breeding season). Note in this specimen the hair on the back has turned to grey. Photo: Kaoru Kusunoki, Tama, 2017-09-09

winter coat: no descriptions found

Golden Takin female in February. Overall pelage colour is brownish without the golden tone – except for the beard and lower limbs. Photo: Kaoru Kusunoki, Tama, 2017-02-25

face: never becoming dark [13]

tail: bushy, occasionally with isolated dark hairs [2]

Golden Takin male in February. In this specimen the pelage doesn’t show any black except for the tip of the nose. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Chumotov

dorsal line: not darkend; present in juveniles, fades away by 6 months of age [2]

young: born dark, but the hair lightens to a grey tinged with yellow [2]; light golden-brown, with dark zones only on the haunches; face wooly light toned [4]

Rumours concerning the Golden Fleece

Fritz Rudolf Walther (Grzimek, 1988) quotes H. S. Wallace, who observed Golden Takins in the Qinling Mountains in 1913, saying: more than anything else we were surprised by its colour. It was the reincarnation of the Golden Fleece … [5] Speculations probably started here that the Golden Takin could have something to do with the tale of the Golden Fleece of a ram named Chrysomallos (Greek mythology). But it is not known if the Takin was known to the antique Greeks. [7] Howsoever a depiction on an Apulian calyx krater from the Louvre, Paris, shows a head that quite clearly resembles a ram and not a Takin.

Jason returns with the Golden Fleece – shown on an Apulian calyx krater (340-330 BC). The animal depicted is rather a ram and not a Takin. Photo: Wikipedia, puplic domain

Horns

As in all Takins horns grow slightly upward, and then turn outward and backward with the horn tips upward. Males have larger horns than females. [16]

Golden Takin male – presumably younger than the male on the photo above (bases of horns seem to be less pronounced). Photo: Jun Tendo, Tama, 2013-06-03

horn length, males: ranging between 45 and 58 cm [2]; up to 64 cm [16]

horn basal girth, males: up to 38 cm [16]

tip-to-tip spread (recorded for 6 specimens): 22,2 to 36,2 cm [2]

Rowland Ward has only 6 entries for Golden Takin.

Table 1: The two biggest Golden Takin trophies listet at Rowland Ward [2]

| number | year | horn legth | circumference |

| 1 | 1913 | 57,8 cm | 26,7 cm |

| 2 | 1999 | 52,4 cm | 29,5 cm |

Safari Club International (SCI) lists 11 trophies taken between 1994 and 2005. The length of both horns across the boss varies between 95,9 cm and 56,5 cm and the width of the boss (measured over the base of one horn) is between 18,7 cm and 30,8 cm. [2]

Habitat

Distribution records of its occurrence have been collected between 1.500 to 3.600 metres [6] and 1.300 to 2.800 metres respectively. [16] Golden Takins use different plant communities.

Table 2: Plant communities used by Golden Takins [16]

| deciduous forest and mixed coniferous broadleaf | 1.000 to 2.200 m |

| subalpine coniferous zone | 2.200 to 2.900 m |

| subalpine meadows | above ca. 2.750 m |

Golden Takin male crossing a creek at a valley bottom in Foping Nature Reserve in November. After noting the photographer the Takin took shelter in the bamboo thickets. Photo: French Connection/Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China

Entrance to a Takin Cave. Golden Takins at Foping Nature Reserve are known to enter caves, most likely to find protection from adverse weather conditions. Photo: Ralf Bürglin/Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China

Inside the Takin Cave. The floor is covered with Takin pellets. Photo: Ralf Bürglin/Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China

Food and feeding

A study shows: Golden Takins feed on 163 plant species and are primarily browsers, with twigs, shoots, stems, leaves, and bark being important dietary components. [16] They also eat grasses, bamboo shoots, forbs, and leaves of shrubs and trees. [6]

Salt licks influence the movement patterns of Golden Takin and the location and size of their home ranges. [16]

Mortality / predators

Predation is not a major mortality factor. [16]

Breeding

sexual maturity: females at 4,5 years; males at 5,5 years [6, 16]

rutting season: June to August [16]; early June to the end of July, with a peak from mid-June to mid-July [6]

gestation: 220 days [16]

lambing season: February to March [6, 16]

birth sites: in deciduous broadleaf or mixed coniferous and broadleaf forests, high on south-facing slopes (2.000 to 2.400 metres) with less than 5 per cent snow cover, or in thick bamboo communities or against a steep slope. Females give birth in female herds and do not segregate newborns. Calves are able to follow their mothers soon after birth. [16]

Newborn Golden Takins. Note their darker pelage. From this it can be derived that the Golden Takin originates from a darker Takin form. Photo: Ralf Bürglin/Liberec

Newborn Golden Takins. Note the raised, dark dorsal line in the young to the left. The dorsal line fades away by 6 months of age [2]. Photo: Ralf Bürglin/Liberec

Activity pattern

During spring and summer, Golden Takins are most active feeding, standing, and walking at about 6:00 to 8:00 h, 10:00 to 12:00 h, and 18:00 and 20:00 h. There is one active peak at night at 0:00 to 1:00 h. They most actively feed at 6:00 to 7:00 h and 18:30 to 19:30 h. [16]

Movements, home ranges and social organisation

The Golden Takin is gregarious [2]. Elevational movements occur four times a year.

Table 3: Elevations used by Golden Takin according to season [16]

| summer | (June to August) | at 2.200 to 2.800 m |

| winter | (December to March) | at 1.900 to 2.400 m |

| spring | (April to May) | at 1.400 to 1.900 m |

| autumn | (September to November) | at 1.400 to 1.900 m |

Major factors that instigate these seasonal movements are solar radiation and vegetation phenology. [16]

Mean seasonal home ranges of four takins were 19,5 km² in summer, 22 km² in autumn, and 11 km² in winter. [16]

Within a nature reserve, mean group size of herds was 10,8 takins, with a maximum herd size of 59. 50 per cent of the animals were in herds larger than 15, and 53 per cent of groups had more than one adult female. Mean group size of herds formed by adults with subadults or calves was 14,8, and 63,3 per cent of herds had more than one subadult or calf. Only one all-male herd was recorded. [16]

The adult sex ratio was 49 males:100 females. The population consisted of: 17,3 per cent males, 35,4 per cent females, 35 per cent subadults, 12,2 per cent calves [16]

In another study, mixed group composition was unstable because subadults moved between herds. Home ranges of subadult females were larger than those of adult females. [16]

Solitary individuals / males were common, especially during the mating season. [16, 6] Most solitary, old males were seen during winter at lower elevations. [6]

Densities were 1,29 to 1,56 ind/km² in a high-density population within a protected area, but the range of densities in the Qinling Mountains was 0,14 to 0,22 ind/km². [16]

Status

IUCN classifies the subspecies Budorcas taxicolor bedfordi as „vulnerable“. Date assessed: 30 June 2008 [6]

The total population size in Shaanxi was estimated at 5.069 individuals (range: 4.418-5.720; Forestry Bureau of Shaanxi Province 2001). Earlier Ge (1990) indicated 21.200 individuals.

In 1974, a field survey of five areas gave the following numbers of takin: Foping: 104; Taibai: 191; Yangxian: 225; Zhouzhi: 587; and Ningshan: 135 – Total: 1.242 (Wu et al., 1987)

A census by counting individuals in Foping Nature Reserve from April to July 1996, there were 435-527 individuals there with a ratio of adult females: subadults: calves of 1:0.99: 0.35 (Zeng et al. 1998). [6]

Threats

Human encroachment and disturbance due to roads and poaching are concerns, as well as habitat loss and fragmentation even within nature reserves. [16]

Conservation

The subspecies is currently protected by legal statute (the National Wildlife Protection Law of 1988) and nature reserves in Shaanxi. Both distribution and number seem to have increased in recent years. As of 2003, fourteen nature reserves, occupying about 3.250 km² have been established for the protection of Takins and their habitat. Logging bans established in the late 1990s greatly improved the habitat conditions and security for the Golden Takin. [6]

Recreational Hunting

not taking place

Ecotourism

Mammal watchers have reported sightings from Foping Nature Reserve, but the reserve is – as of 2019-02 – not open to the puplic any more. Christoper R. Scharf, a contributor to this chapter, has taken photos of Golden Takin in Changqing Nature Reserve, near Huayang Village, Qin Mountains, Shaanxi province.

Literature cited

[1] Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princeton University Press

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[4] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[5] Grzimek, Bernhard (Hrsg.), 1988: Grzimeks Enzyklopädie, Säugetiere, Band 5. Kindler Verlag, München

[6] Song, Y.-L., Smith, A.T. & MacKinnon, J. 2008. Budorcas taxicolor. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3160A9643719. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3160A9643719.en. Downloaded on 25 February 2019.

[7] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[10] Schaller, George B., 1977: Mountain Monarchs – wild sheep and goats of the Himalaya. The University of Chicago Press

[12] Shackleton, D. M (ed.) and the IUCN/SSC Caprinae Specialist Group, 1997: Wild Sheep and Goats and their Relatives. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan for Caprinae. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. 390 + vii pp

[13] Smith, Andrew T. and Xie, Yan, 2008: A guide to the mammals of China. Princeton University Press

[16] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Photo gallery

Golden Takin male in September. Colour on the back has turned to whitish-grey. Photo: Kaoru Kusunoki, Tama, 2017-09-09

Golden Takin male in February. Saddle of this specimen is only rudimentally greyish. Photo: Kaoru Kusunoki, Tama, 2017-02-04

Fresh Takin droppings in November. Diameter of ring: 2 cm. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China

Takin droppings in November. Diameter of ring: 2 cm. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China

Takin tracks. Diameter of ring: 2 cm. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Foping Nature Reserve, Qinling Mountains, China