The Himalayan Serow’s most prominent feature is its trichromatism, being reminiscent of the old Berlin flag: black-red-white – overall blackish above; turning to rusty red on flanks, hindquarters, and upper legs; whitish on lower legs.

Himalayan Serow – presumably female. Pelage color is striking. Memory hook: like the old Berlin flag – black-red-white. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Names

Assamese: Deo sagoli (5)

Bengali: Jongli chagol (5)

Bothia (Sherpa language): Gya (5)

Dzongkha (Bhutanese language): Jha – pronounced as [d͡ʒʱə] or [d͡ʒʱ] (pers. comm. Sangay Dorji – Bhutanese guide)

English: Himalayan Serow, Nepalese Serow, Western Serow (3)

French: Serow de l‘ Himalaya (3), Saro du Himalaya (3),

German: Himalaya Serau (1), Nepal Serau (3)

Hindi: Sarao (5)

Kashmiri: Halj

Mizo (Tibeto-Burman language): Saza (5)

Naga (Sino-Tibetan language): Tellu (5)

Spanish: Sirao del Himalaya (3)

Taxonomy

Capricornis thar Hodgson, 1831

Type locality: Nepal, Himalayas (4)

monotypic, but Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) believe the light-red serow from the Garo, Mishmi, and Naga Hills (Northeastern India) „has been mistaken for the Red Serow (C. rubidus) but is actually much closer to the Himalayan Serow (C. thar).“ (3) If this was the case, this red form should get subspecies rank. Furthermore: If you compared the pattern of Himalayan Serow forms with the many subspecies of chamois in Europe, it seems to be appertain to reconsider the former subspecies splits of the Himalayan Serow (see below).

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms

Antilope thar Hodgson, Nepal, Himalayas, 1831 (4)

Antilope bubalina Hodgson, Nepal, 1832 (4)

Capricornis thar bubalina Hodgson, 1832 (1)

Nemorhaedus (Kemas) proclivus Hodgson. Alternative for Antilope thar, 1842 (4)

Capricornis thar proclivus Hodgson, 1842 (1)

Capricornis sumatraensis humei Pocock, Kashmir, 1908 (4)

Capricornis thar humei Pocock, 1908 (1)

Capricornis sumatraensis jamrachi Pocock, Kalimpong near Darjeeling, 1908 (4)

Capricornis thar jamrachi Pocock, 1908 (1)

Capricornis sumatraensis rodoni Pocock, Chamba, Punjab 1908 (4)

Capricornis thar rodoni Pocock, 1908 (1)

The taxonomic validity of this species, and its relationship to other species in the genus Capricornis needs to be assessed. (2)

Distribution

This species is known to occur in the Himalayas (Northern India – from Jammu and Kashmir to the Mishmi Hills in Arunachal Pradesh -, Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet), as well as further south in Northeast India, probably Western Myanmar and East and Southeast Bangladesh. (2) However specimens from Northeast India, Western Myanmar and Bangladesh clearly differ from the Himalaya forms in that they feature a red pelage. Accordingly specimens from these more southerly areas might be a different taxon (be it a different subspecies or species – yet undescribed). Read more in the Red Serow chapter.

In China (Tibet), only two places are mentioned. Both are on the southern slopes of the Himalayas: the narrow area on the south slope of Qomolangma on the border with Nepal. The second population is found in the narrow area east of the Big Bend of Yarlung Zangbo River (Feng et al., 1986). (2)

General description

Himalayan Serow from Bhutan – presumably female. Note the overall bolder pelage colours . Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Himalayan Serow from Nainital, about 1000 km west of Bhutan. Note the overall less colorful pelage. Photo: Nainital Zoo, Uttarakhand, India

length / head-body: 140-170 cm (3);

shoulder height: 90-100 cm (3); old rams: 100-120 cm (1)

weight: 85-140 kg (3); old rams: over 90 kg (1)

pelage: jet-black (4), dark black, coarse hair (3), with straw or white hair bases that show through. Black tips ot the hair becoming redder lower down the flanks, but sometimes acquiring a buffy tone as the black tips wear off. (4)

Damm and Franco (2014) write that „body coloration varies considerably throughout its range“. (1) This seems to apply mainly if the light-red form from Northeastern India, Myanmar and Bangladesh is seen as a subspecies of the Himalayan Serow. On the other hand my overall impression (not statistically veryfied) is that there is a spreading of color patterns comparable to the Himalayan gorals with lighter, paler forms in the west, becoming gradually darker as you move eastwards.

underparts: sharply cream-buff (4), paler (3); inner surfaces of the thighs creamy, continuous with the light underside (4). Both specimen shown here – from Nainital (western part of the range) and Bhutan (more easterly) – feature reddish-white hair. The animal from Bhutan has a distinct white breast spot.

Himalayan Serow showing its underparts, which are cream-buff . Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

dorsal stripe: sometimes visible, but not usually marked so (4); specimen from Nainital shown here with very distinct dorsal stripe

mane: long, mixed black and white (3, 4), varying, but never with the white predominating (4); black in specimens from Nepal and Bhutan (1)

Himalayan Serow. Note the mane which is overall black. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

tail: black (1). Both specimen shown here – from Nainital and Bhutan – feature black, red and white hair.

Hindquarters of a Himalayan Serow. Note the black tail stripe merging into the dorsal stripe. Photo: Nainital Zoo, Uttarakhand, India

legs: black hair tips on the legs becoming red lower down, and pure white hairs increasingly intermix, with the legs thus becoming creamy white shortly below the „knees“ and the hocks, sometimes with a buffy line down the front. (4)

head / face: comparatively large (1); forehead flatter than in Sumatran or Burmese Serow (4); preorbital gland present (3); head sometimes lighter than the body (4); prevailing black coloration in specimens from Chumbi/Sikkim, Nepal and Bhutan; brownish black in specimens from Chamba/India – central part of the range; pale chocolate brown in specimens from Kashmir (1). White areas: broadly white over the nose, or only on the lip margins; white extending along the jaw lines, backward in a V, or the interramal region (area between the lower mandibles) completely white, or occasionally nearly absent. (4)

Portrait of a Himalayan Serow. Note the white on nose, lips, inner ear and on the nasal ridge. Photo: Nainital Zoo, Uttarakhand, India

Himalayan Serow. Note the protuberant preorbital gland. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Himalayan Serow. Note the straight facial profile. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Himalayan Serow. Note the white on the edge of the mouth and a rust-red throat patch, that seems to be not typical. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

ears: prominent long (3); almost donkey-like, inside whithish (1)

horns: male’s 16-34 cm; male horn girth 10-15 cm; female horns have thinner horn girth (3)

Horns

Male horns measure 16-34 cm. Horn girth in males is 10-15 cm; female horns have thinner horn girth (3) Horn color is black. (5) (The largest trophy was collected in the Sironchock Mountains in Nepal in 1982, when hunting of serow was still legal. The horns of this trophy reached 34 cm in length and had a base circumference of 14,9 cm. The mean figures are: horn length 24,4; circumference 13,2 cm and tip-to-tip spread 10,2 cm

Himalayan Serow. Horns of this specimen seem to have a granular surface. Photo: Nainital Zoo, Uttarakhand, India

Similar species

The Himalayan Serow is bigger than the Sumatran Serow. (5) The Sumatran Serow is overall black, the Red Serow red. The Chinese Serow does not show the white lower legs. Himalayan Gorals are smaller, are either grey or brown and to not feature the typical trichromatism of the Himalayan Serow.

Habitat

The Himalayan serow is widespread but sparsely distributed throughout the forested southern slopes of the Himalaya between 300 and 3.000 m. (2) In general the Himalayan Serow is found in densely vegetated habitats including temperate broadleaf, coniferous, and subalpine forests, bamboo thickets, and thickly forested gorges. Tall vegetation provides forage and thermal cover. (3)

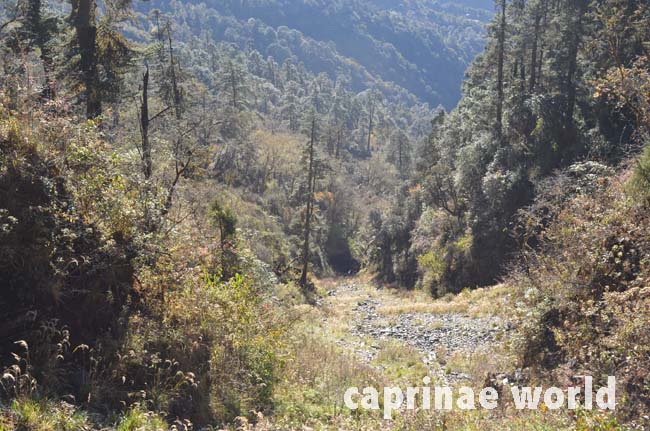

Roadside Serow habitat near Pelela-Pass, Bhutan at 3270 m. Old growth coniferous forest with dense undergrowth make observations of the species extremely difficult.

In Assam they may come down to 100 m in winter. It occurs from tropical rainforest and deciduous forest in Assam to subtropical and temperate forest, both conifers and broadleaf, in Arunachal Pradesh. (4)

It inhabits rugged steep hills and rocky places, especially limestone regions, but also gentler terrain. In the Western Himalaya Serow habitat is generally at higher elevations than the areas of intensive agriculture. Serow requires denser habitat than goral. (2)

Habitat by countries: In Bhutan it is known to occur in subtropical and temperate zones, and has been recorded in Royal Manas and Black Mountain National Parks (NCS, 1995). In Nepal it is probably also widespread throughout the forested mountain slopes (2); it has been recorded at 2500-3500 m on slopes with a 20-40 % gradient; it is not observed above 4000 m. (3) In the few places in China (Tibet), it occurs only on southern slopes in the forest belt between 2.000 and 3.000 m. (2)

Mortality / Predators

In winters with heavy snowfalls, avalanches can cause considerable mortality. (2) Main predators: leopard, dhole, eagles (5)

Food and feeding

Principally a browser (3)

Breeding

mating: October-November (3)

gestation: 210 days (3)

birth period: May-June (3)

young per birth: typically single young (3)

Himalayan Serow. The squatting position while staling suggests a female. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Activity patterns

usually diurnal. (3)

Movements, home range and social organisation

No estimates of population size are available in India, but density in good habitat within Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (Uttaranchal) has been estimated at 1.6 serow/km² (Green, 1987a). (2) In Nepal, densitiy is 1,2 ind/km2 (3) In Bangladesh numbers are believed to be very low, as are densities. Population in China are also believed to be small (Feng et al., 1986). (2)

Within some protected areas, serow populations may approach maximum densities of 2 animals/km². However, its apparent preferred habitat of steep, thickly vegetated slopes, is so patchily distributed that overall densities are low and serow is relatively rare throughout its range. (2)

Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) state that Himalayan Serows are „usually observed in small groups of less than ten“. (3) This figure is rather doubtful since all other serow species are in gerneral solitary animals. Furthermore the above mentioned maximum densities of 2 animals/km² would not match. (I assume that the observer (source not clear) mixed up serows with gorals.)

When Himalayan Serows are alarmed, they bounds away with a hissing snort or a whistling scream. (5)

Threats

The Himalayan Serow is listed as „Near Threatened“ on the IUCN Red List.

Habitat destruction and hunting for food and traditional medicine are mentioned as threats. (2) Furthermore agricultural activities, uncontrolled tree cutting, and livestock competition (especially Domestic goats feeding in rugged terrain, degrading habitats in areas not accessible to other livestock) are other major causes of declining serow populations. (3) Since serows require denser habitat it is likely to be more susceptible to deforestation and removal of understory vegetation. (2)

In India habitat destruction, especially loss of forest understory due to clearing for agriculture and to collection of fuelwood, is probably the main threat to serow (Green, 1987b). Where cultivation is less extensive, especially in the Eastern Himalayas, hunting for meat and trophies is the most important influence on serow populations.

In China and Nepal the main threat is probably hunting / poaching.

In Bangladesh habitat disturbance and poaching are the greatest threats to its survival, both related to slash and burn (jhoom) cultivation (Khan, 1985). (2)

Conservation Status / Action

In India the Himalayan Serow is totally protected – listed in Schedule I (revised March 1987) of the Wildlife (Protection) Act (1972). This status has been accepted by all Indian states except Nagaland. (2)

Within India, the Himalayan Serow occurs in a number of protected areas in Himachal Pradesh, Uttaranchal, and Sikkim, as well as a few protected areas in Manipur, Meghalaya, and Mizoram (Kathayat and Mathur (2002). In total, it is present in over 50 Indian protected areas, ranging in size from 4 km² to 1,800 km², and totaling about 17,000 km². However, many of these areas include substantial habitat unsuitable for serow and it is has been suggested that only some 6,000 to 8,000 km² of ca. 19,000 km² of good serow habitat in India, lies within protected areas (Johnsingh, 1991; Johnsingh et al., in prep. H). (2)

Himalayan Serow occur in the following protected areas in India (Fox et al., 1986; Green, 1987b; Kumar and Rao, 1985; Lamba, 1987; S. Pandey, 2002; Singh et al., 1990): Jammu and Kashmir – Dachigam National Park and Overa-Aru Wildlife Sanctuary; Himachal Pradesh – Great Himalayan National Park and the Daranghati, Gamgul Siya-Behi, Kalatop, Kanawar, Khokhan, Kugti, Manali, Naina Devi, Rupi Bhaba, Sechu Tuan Nala, Tirthan (possibly) and Tundah Wildlife Sanctuaries; Uttar Pradesh -Nanda Devi National Park, Govind Pashu Vihar and Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuaries; Sikkim – Khangchendzonga National Park; Arunachal Pradesh – Namdapha National Park; Meghalaya – Balphakram National Park. However, the species is considered to be locally threatened even within some of these protected areas (e.g. Great Himalayan National Park and Daranghati, Manali, Tirthan and Tundah Wildlife Sanctuaries). (2)

Conservation measures proposed for India: 1) Establish the proposed Srikhand National Park, Himachal Pradesh. 2) Develop a management program for maintaining serow habitat and sustaining hunting outside protected areas. Habitat alteration and hunting will continue to negatively affect serow populations throughout northern India, and because serow is apparently dependent on patches of dense vegetation associated with rugged terrain, the alteration or elimination of such vegetation will be highly detrimental to the species. Management to control habitat alteration, prevention of overhunting outside protected areas, and effective protection in parks and sanctuaries, will be required to maintain viable populations in the future. (2)

In China, it is a Class II nationally protected species. There are two reserves in Xiaca and Muotuo. And there is the Qomolangma Nature Reserve, on the Sino-Nepal border, an international protected area. Conservation measures proposed for China: Undertake censuses to determine population status and distribution, including surveys in the Chun-pi valley. (2)

In Bhutan, it is listed in Schedule I of Bhutan’s Forest and Nature Conservation Act, 1995. Himalayan serow is reported in Royal Manas National Park on the southern border with Assam (Jackson 1981). It also lives in the vast Jigme Dorji National Park (Blower, 1989; Wollenhaupt, 1988d), and in Black Mountains National Park (Blower, 1989). Conservation measures proposed for Bhutan: Surveys to determine numbers and distribution. (2)

In Nepal, it occurs in the following National Parks: Royal Chitwan, Lake Rara, Langtang, Sagarmatha, Makalu-Barun (and Conservation Area), Khaptad, and Shey-Phoksundo. It is also found within the Annapurna Conservation Area, and in Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve. The species probably occurs in Parsa Wildlife Reserve, and possibly also in Royal Bardia National Park, but these locations need to be confirmed. Conservation measures proposed for Nepal: 1) Conduct censuses and 2) studies of population demographics, to 3) develop specific conservation plans. (2)

Trophy Hunting

not a factor

Ecotourism

negligible

Mammal watchers do mention Himalayan Serows, when they encounter them, but usually don’t actively search for them. Usually their habitat is too confusing. Photo taken at: Motithang wildlife reserve, Thimphu, Bhutan

Literature cited

(1) Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

(2) Duckworth, J.W. & MacKinnon, J. 2008. Capricornis thar. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3816A10096556. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3816A10096556.en. Downloaded on 03 May 2017.

(3) Wilson, D.E. and Mittermeier, R.A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. Hoofed Mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

(4) Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press.

(5) Castelló, José R., 2016: Bovids of the World – Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives. Princton University Press.