The Pyrenean Ibex is an extinct subspecies of the Iberian Ibex, which died out in 2000. „Pyrenean Ibexes“ found today are introduced (2014) Victoria Ibex.

Names

English: Pyrenean Ibex, bucardo [2]

French: bouquetin des Pyrénées [Wikipedia]

German: Pyrenäen-Steinbock

Portuguese: íbex-dos-pirenéus [Wikipedia]

Spanish: bucardo [Wikipedia]

Taxonomy

Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica, Cabrera 1911 [2]

Other (putative) scientific names and synonyms: none known

The Pyrenean ibex was first described by Heinrich Rudolf Schinz in 1837 on the basis of a young male Ibex in the Museum of Zurich and on the basis of figures from three specimens – an old male, a female and a juvenile male – from the Mainz Museum of Natural History, which were sent to Schinz by the Mainz notary Carl Friedrich Bruch, chairman of the „Rhenish Natural History Society“ (Rheinisch Naturforschenden Gesellschaft) [7]. Photos of all three specimens are depicted in this chapter.

Distribution

The Pyrenean Ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) occured in the Pyrenees, in Spain, Andorra and France. Lastly it was to find only in Ordesa National Park, province of Huesca, Spain (Maas 2011b). [6]

Engländer (1986) describes that Iberian Ibex (C. pyrenaica) occured formerly also in South West France during the ice age (early Upper Pleistocene). It became replaced in the latest Pleistocene by the Alpine Ibex (C. ibex). [3] It is not clear if the original form belonged to the Pyrenean Ibex (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica).

On the other hand it is said that the distribution range of the Portuguese Ibex (Capra pyrenaica lusitanica) extended from Northern Portugal throughout the Spanish provinces of Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria. [6] It is not known where the separation line with the Pyrenean Ibex ran and if the distribution range of the Pyrenean Ibex extended beyond the Pyrenees towards west.

Course of extinction

In the 14th century the subspecies was still common (Cabrera 1914). Until the mid-19th century it disappeared gradually from further areas of its former range. At the beginning of the 20th century only one population consisting of 100 heads lived in the north of Spain (Perez et al. 2002). Not until 1973 it received conservation status. In 1981 only three individuals remained, and at the end of the 1980ies there were between 6 and 14 animals left (Caprinae Species Group 2000). The last birth in the field was documented in 1987 (Perez et al. 2002). 1993 only 10 animals were known. On January 6th 2000 the last specimen, 13-year-old female „Celia“, died under a fallen tree (McCarthy 2000). [6]

The main reasons for the disappearance of the Pyrenean Ibex – and Portuguese Ibex, and the falling numbers of the two other subspecies – is undoubtedly indiscriminate hunting in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the expansion of livestock grazing and agriculture into remote mountain areas. [2]

Other reasons for the extinction have been discussed (Caprinae Species Group 2000) [6 – if not otherwise spedified]:

- inferiority to domestic animals or resident Chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica pyrenaica)

- infections or illnesses, spread through domestic animals,

- poaching

- sterility / low fertility due to plant secondary compounds [5]

- inbreeding

- climatic changes

Conservation through breeding in captivity failed with the death of the last male in 1991. The remaining females should have been interbred with individuals of the subspecies hispanica, which were introduced to the Pyrenees, but again the attempt failed (Perez et al. 2002). [6]

In January 2009 for the first time an extinct animal taxa was brought back through cloning. The cell samples had come from „Celia“, which were implanted into a domestic goat. A female young was born, which died only a few minutes after birth (Brahic 2009, Maas 2011b). [6]

Preserved specimens

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Table 1: Locations of preserved specimens and published photographs of Pyreneen Ibex

| specimen | location | source / remarks |

| bucardo head, harvested in 1959 | National Park Office at Ordesa | [2] |

| Laña/Celia – mounted specimen: last Ibex of the Pyrenees | Centre d’accueil de Torla / Centro De Visitantes Parque Nacional; Torla-Ordesa, province of Huesca, Aragon, Spain. ((editor’s note: same location as above?)) | [12] |

| mounted male and female | Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris | photographed by the author; photos included in this chapter |

| mounted male | Naturhistoriska riksmuseet, Stockhom | photographed by P. Hrabina; photos included in this chapter |

| three mounted specimen (male, female, juvenile) | Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz, Germany | photos included in this chapter |

| type specimen of the Pyrenean Ibex along with another male specimen | collection of the University of Zürich, Switzerland | [12] |

| male specimen | museum in Strasbourg, France | [7]; sent by Carl Friedrich Bruch from the stock of the Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz, Germany |

| male specimen | museum in Vienna, Austria | |

| male specimen | museum in St. Petersburg, Russia | |

| a head | Musée de Bagnères in Luchon, France | [12] |

| skull | Nantes Museum, France (= Natural History Museum, Nantes?) | [12] |

| mounted skin of the last female | collection of taxidermist Julián Causapié in Zaragoza, Aragón, Spain. | [12, 13] |

| skulls and horns of the last two females | Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología (CSIC) in Jaca, Aragón, Spain | [12] |

|

scull fragment, specimen USNM 174944; collector: W. Schluter, Spain (no exact location given), unknown date scull; specimen USNM 200162; collector: K. Rehder, Spain (no exact location given), 1915-08-23 |

collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (Washington/USA) | [2] |

| one of the last photographs taken of a live bucardo male | in de Camps-Galobart’s book „Conversaciones sobre el Macho montés“ (2009:49) ((editor’s note: book is not listet in Bibliography of [2] and could also not be found anywhere else)) | [2] |

| scull | Basel, Switzerland | [13] |

| mounted head, male | Museo Muncipal de Bagneres de Luchon, France | [13] |

| mounted male | Natural History Museum Bordeaux, France | [13] |

| stuffed male | Natural History Museum Toulouse, France | [13] |

| scull, young male | Cercle anglais en Pau, France | [13] |

| male scull | Natural History Museum Dublin, Ireland | [13] |

Description

Editor’s note: In general it has to be noted that many of the descriptions presented here are based on one or few specimens or by „looking at photographs“, which does not meet scientific standards.

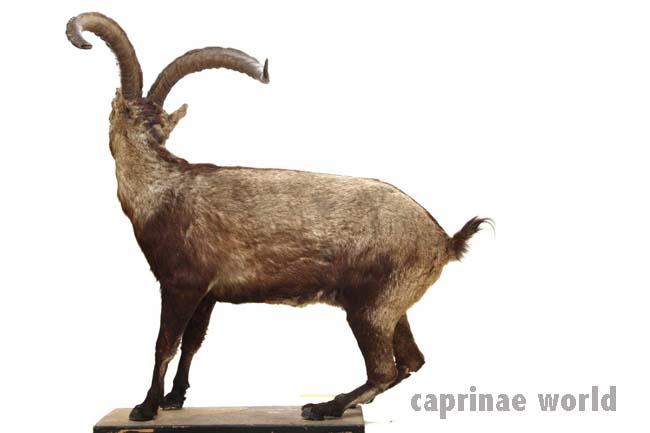

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz; right side [2] with fire damages (orangy spots?; see text); about eight to ten years old. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

The Pyrenees ibex from the mammal collection of the Rheinisch Naturforschenden Gesellschaft is one of the few specimens that survived the bombing of the Natural History Museum on February 27, 1945. Unfortunately it shows minor fire damages on the right hand side. [7]

length of one specimen seen by Cabrera (1914): 148 cm [6]

shoulder height: 75 cm [6] – (n=?)

The „bucardo“ is reported to have been physically larger and stouter than the extant races (Alados in Camps-Galobart 2009:87). [2]

ears: 12,6 cm [6] – (n=?)

tail: 13 cm [6]

Colouration / Pelage

According to Matschei (2012) the pelage of the Pyrenean Ibex is rather contrasty [6] – see also text below

pelage of males during summer: greyish-brown [6]

sides and chest up to the front neck in males: black [6]

dorsal line: black; broadening to a big spot between the shoulders [6]

head: brown; with black forehead [6]

goatee: short, dark [6] – only in males

forelegs and front of hind legs: black [6]

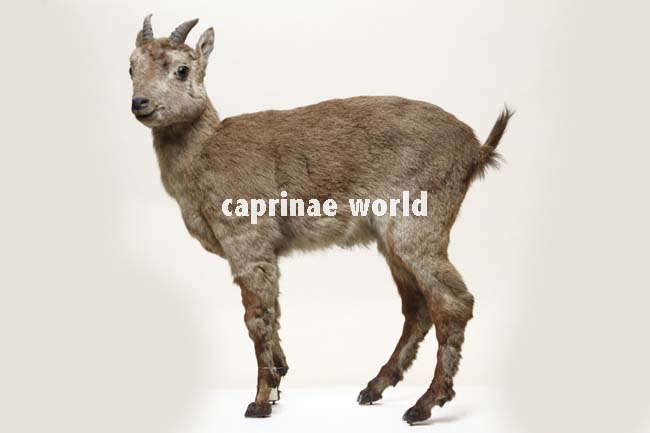

pelage of ewes during summer: fawn, without dark flanks and dorsal line

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), left side, at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), right side / front, at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

The male from the Natural History Museum Mainz is about eight to ten years old and shows the typical colour pattern of mature males, which in contrast to the red-brown of females, tends more to gray-brown, with expanding black fur on legs, flanks and neck. [7]

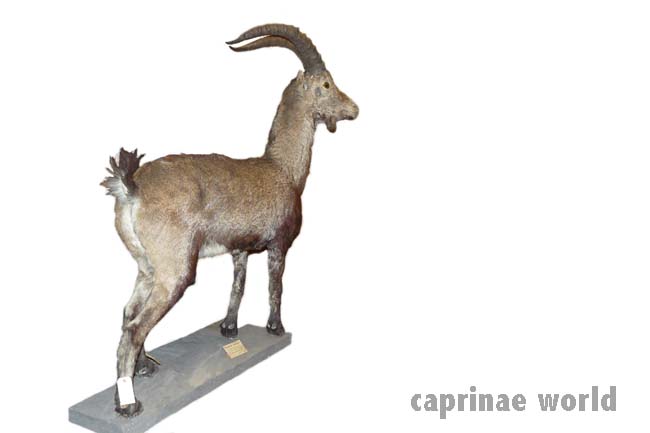

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), about 7 years old, at Naturhistoriska riksmuseet, Stockholm. Note that the black marking in the posterolateral area – in contrast to the general description – is not very pronounced. Photo: Petr Hrabina / image editing: Ralf Bürglin

Pyrenean Ibex female (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Pyrenean Ibex female (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz / N. T. Back

Pyrenean Ibex male juvenile (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz / N. T. Back

Groves and Grubb (2011) assume a „cline in colour, the northern Ibexes being darker, with a more strongly expressed pattern of dark markings; although in the Sierra des Gredos, in Central Spain, the dark markings may be often so strong that in summer they seem almost black. “ [3]

Matschei (2012) sees two clines in pelage contrast, one increasing from south to north, and one increasing from west to north. Therefore he sees the Pyrenean Ibex as the most conspicuous subspecies and the Hispanic and Portuguese forms as the most unremarkable. [6]

Horns

Groves and Grubb (2011) mention the horn peculiarities of a Pyrenean male specimen from the British Museum (the only one they have seen from this population): „At the base, the horns are broader anteroposteriorly than in any other specimen, with prominent round knots along an anteromedian ridge (but not extending across the front of the horns, as in C. ibex). If enough localized material becomes available, another look at infraspecific variation would be advisable.“ [3]

Having looked at two historic photographs (Rodriguez de la Zubia 1969:28, plate 7) Damm and Franco (2014) confirm that the horns of the bucardo were „considerably shorter and stouter than the horns of the Victoria and Hispanic Ibex and „very thick at the base, holding the mass at least throughout the first and second quarter.“ Apparently the configuration of the bucardo horns was more open, with a pronounced backward curve, and a less obvious keel than the Victoria phenotype (Rodriguez de la Zubia 1969:28; Almendral 1979:136; Camps-Galobart 2009:27) [2]

horns of males: thick and massive. [6]

horn length (outer line), male (of one specimen): 80 cm [6]

largest recorded bucardo horns: horn length of 87,6 cm; from a 16-year-old male, taken in the early 1900s in Ordesa (Camps-Galobart 2009:40). [2]

male horn tip to tip spread (of one specimen): 42 cm [6]

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), portrait right side, at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), portrait left side, at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), posterior view, at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz

Pyrenean Ibex male (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), about 7 years old, at Naturhistoriska riksmuseet, Stockholm. Photo: Petr Hrabina / image editing: Ralf Bürglin

female horn length: 26 cm [6]- (n=?)

female horn tip to tip spread: 18,7 cm [6]- (n=?)

Pyrenean Ibex female (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz; collected 1836 at Maladette Pass, on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz / N. T. Back

Pyrenean Ibex male juvenile (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) at Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz; collected 1836 at Maladette Pass, on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees. Photo: Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz / Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz / N. T. Back

Literature cited

[2] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC InternationalCouncil for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa

[3] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate Taxonomy. The John Hopkins University Press

[5] Herrero, J. & Pérez, J.M. 2008. Capra pyrenaica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species2008: e.T3798A10085397. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3798A10085397.en. Downloaded on 21 May 2019.

[6] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine & Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[7] Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz, Landessammlung für Naturkunde Rheinland-Pfalz: Pyrenäen-Steinbock – Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica (Bock), 2017-04-29. https://rlp.museum-digital.de/index.php?t=objekt&suinin=13&suinsa=89&oges=2697&cachesLoaded=true. Date of retrieval: 2019-06-05

[12] Maas, Peter: Pyrenean Ibex – Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica – The Sixth Extinction. URL: https://petermaas.nl/extinct-archive/speciesinfo/pyreneanibex.htm. Date of retrieval: 2019-05-29

[13] Woutersen, Kees: El Bucardo (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica). URL: http://www.bucardo.es/. Date of retrieval: 2019-06-06