Serows are small to medium-sized, goat- or antilope-like caprinae species. They are the most generalized representatives of the subfamily. Therefore it is thought that all Caprinae species evolved from a serow like ancestor. [1] The serows are four to seven species, living in East-, South- and Southeast Asia.

Names

The name „serow“ comes from the Indian-Mongolian Lepcha word „saro“. The latin word „Capra“ means a she-goat, „cornu“ the horn of an animal, hence „Capricornis“ implies the presence of goat-like horns. [1]

The word „thar“ is used as the scientific species name for the Himalayan Serow (Capricornis thar). However the Idu Mishmi People – from Arunachal Pradesh, far Northeast of India – use the term „thar“ in their language too, to describe the serow (personal conversation with local guide Drama Mekola from Roing, during a trip to the Mishmi Hills in 2017). This leads to confusion since the english term „tahr“ is used to describe the Himalayan Tahr (Hemitragus jemlahicus).

Taxonomy

Heude (1898) described a least 24 supposedly different serow taxa. Later authors have united some and added others. Even today, authors differ strongly on nomenlature and specific/subspecific status of the various types. Not surprisingly, physical descriptions and distributon range maps differ and assessments of serow conservation stats vary, wht little in the way of conclusive scientific evidence. [1]

Schaller (1977) listet one serow species, Capricornis sumatraensis, with 11 subspecies. Other authors recognized two serow species, Capricornis crispus with two subspecies and Capricornis sumatraensis with five subspecies. Differentiation was mainly based on body size, pelage, and mane presence, colour and length. [1]

The Caprinae Action Plan (1997) lists three serow species: C. sumatraensis with five subspecies (C. s. milneedwardsii, C. s. maritimus, C. s. sumatraensis, C. s. rubidus, C. s. thar) and the two island species C. crispus and C. swinhoe. [1]

Wilson and Reeder (2005) recognize six serow species: Himalayan Serow (C. thar), Chinese Serow (C. milneedwardsi) – with the subspecies C. m. maritimus – , Red Serow (C. rubidus), Sumatran Serow (C. sumatraenis), Japanese Serow (C. crispus), Formosan Serow (C. swinhoe). The IUCN Red List (2008) follows the taxonomy of Wilson and Reeder (2005). [1]

Groves and Grubb (2011) devided the species in two formal groups: „C. sumatraensis group“ and „Other Serow“ [3]. The same two groups are also named more self-explanatorily „mainland serows“ and „island serows“. (Editor’s note: The Sumatran Serow was first described from the island of Sumatra, but is widespread on the Southeast Asian mainland. Most authorities therefore label it „mainland“ serow.) [3]

Wilson and Mittermeier (2011) elevated the Indochinese Serow (C. m. maritimus) from subspecies to species level (C. maritimus) to make it seven serow species alltogether. [9]

Mori et al. (2019) revised the taxonomy and phylogeny of the serows, for the first time using the total mitochondrial genome of all taxa. They confirm the existence of four serow species. They recognise Japanese Serow (Capricornis crispus) and Formosan Serow (Capricornis swinhoei) as well as two species of mainland serow: Red Serow (Capricornis rubidus) and Sumatran Serow (Capricornis sumatraensis). [7]

They further showed that the Red Serow (Capricornis rubidus) – as well as the Red Goral (Naemorhedus baileyi) – are the forms that are more closely related to the common Pliocenic, still-unknown ancestor. The Japanese Serow (Capricornis crispus) is sister to all remaining species. The Red Serow (Capricornis rubidus) and Formosan Serow (Capricornis swinhoei) are sister species, probably the remnants of an older radiation of mainland serows. [7]

Prior to Mori et al.’s study the question remained whether the so called Assamese Red Serow from northeastern India is a colour phase of the Himalayan Serow (C. thar). It was also thought to be a distinct (but yet unnamed) species or subspecies. [1] Using a sample from the Assamese Red Serow distribution range Mori et al. (2019) could proof that their specimen is distinct from the Himalayan Serow.

However not having a sample available from the distribution area of the „true“ [1] Red Serow, the question remains whether the „Assamese Red Serow“ is distinct from the „Burmese Red Serow“. The physical description of Damm and Franco (2014) supports this hypothesis: „True rubidus specimens have a black hair base rather than white.“

Therefore it has to be concluded that serow taxonomy remains unresolved.

Serow species / subspecies

Hereinafter I follow Wilson and Reeder (2005) designating six serow species, including the subspecies Indochinese Serow (Capricornis milneedwardsii maritimus), which comes to seven phenotypes.

Sumatran Serow (Capricornis sumatraensis)

Himalayan Serow (Capricornis thar)

Chinese Serow (Capricornis milneedwardsii)

Indochinese Serow (Capricornis milneedwardsii maritimus)

Burmese Red Serow (Capricornis rubidus)

Japanese Serow (Capricornis crispus)

Formosan Serow (Capricornis swinhoei)

Karyotype

only known for:

– Japanese Serow and Formosan Serow: 2n = 50

– Sumatran Serow: 2n = 54

– gorals: 2n = 56

Similar Taxa

The genus that is closest to the serows is Nemorhaedus, the genus of the gorals. The sovereignty of both forms was formerly not clear. Today morphological, ecological and ethological data as well as molecular studies clearly show that Capricornis and Nemorhaedus are distinct genera. Nevertheless some Chinese sources still label serows as Nemorhaedus.

In general serows are bigger, but the larger goral forms can be slightly larger than the small island serows. Hence some of the apparent, but superficial resemblances between some species of serow and gorals relate to similarity in size [1] and colour. For example Formosan Serow and Himalayan Brown Goral look pretty alike.

Some more serow peculiarities: In serows the preorbital glands are larger [8] and deeply invaginated – more in the Himalayan serow; less deep in the Japanese Serow. [3] The foot gland is bigger in gorals, but communicating directly to the outside (said to be more goral-like in Japanese Serow). [3] In serows a lower canine is present, which generally distinguishes the dental formula of serow from goral [1, 8], although canines are occasionally present in Nemorhaedus [8]. It is also said that serows have a straighter facial profile than gorals [8], but exceptions occur. The zygomatic arch continues below the orbit and onto the face as a sharp crest. The nasal bone length is relatively short (Taiwanese Serow have especially short, broad nasal bones). [3]

Find out more about how to make a distinction between goral and serow?

Distribution

Serows occur from Jammu and Kashmir in India along the Himalayas into China, where they cover southern and southeastern parts. They are also occuring in all southeast Asian countries from Myanmar in the West to Vietnam in the East, extending southward into Malaysia and Indonesia, covering Sumatra to the southern tip. The Japanese Serow is restricted to Japan, the Formosan Serow to Taiwan. The Sumatran Serow – unlike its name suggests – is not a pure island form. It occurs also on the Malaysian and Indonesian mainland.

Many serow species range boundaries are still not clear. It appears that the ranges of Himalayan Serow (C. thar), Chinese Serow (C. milneedwardsi), Red Serow (C. rubidus) and of a yet unnamed reddish serow known as Assamese Red Serow, may meet or even overlap in the border regions between India (Arunachal Pradesh), western and northern Myanmar and China. The unnamed reddish serow reportedly mainly occurs in the border regions of India and Myanmar and was formerly described as a reddish color morph of the Himalayan Serow.

At least one distribution range boundary in the area is distinct: the boundary of the Sumatran Serow (C. sumatraensis) and the Indochinese Serow (C. m. maritimus). The two species are clearly seperated by the Isthmus of Kra [1] - the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula, in southern Thailand and Myanmar – with the Sumatran Serow occuring south of the isthmus.

General description

Himalayan Serow from Bhutan. In general serows are said to have a straight facial profile. This is true for the mainland forms, but less so for island forms. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Pelage colour is either variable (greyish, blackish, brownish or whitish (Japanese Serow) or reddish (Burmese Red Serow, Assamese Red Serow, Taiwan Serow) or blackish (all other mainland serows). Colour variations in „blackish serows“ occur with grey, whitish or rufous areas mainly regarding limbs, manes, dorsal crests, chin, muzzle and throat. The most conspicuous species is said to be the Chinese Serow (Capricornis milneedwardsi) with rufous limbs, whitish throat patch and muzzle and a long (longest of all serow species?), shaggy, silvery or white mane. It is therefore also called „White-maned Serow“. However other mainland serow species can also show long, white manes.

Himalayan Serow from Bhutan. All mainland serows show white pelage patches of some sort, which can be used to determine species. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Sumatran Serow with a very pronounced mane, which is usually said to be typical for Chinese Serow. Photo: Johannes Pfleiderer

Horns: In general the horns of serows are relativly short and of conical shape, rising more or less in the plane of the face with a distinct outward divergence [1], narrowing gradually and evenly along their length, closely ribbed with flat rings to more than halfway along. [3]

Measured serow horns are few, but it can probably be said that average horn length of mature serow rams appears to be around 24,5 cm and the median base circumference rarely exceeds 14,0 cm. The heads with the longest horns were collected in Nepal (34 cm), Myanmar and northeastern India (33 cm). As is expected the island forms from Japan and Taiwan have the shortest horns. For comparison: The longest goral horns do not significantly exceed 20 cm. [1]

The horns of females, which are somewhat shorter [1] and less worn [8] than those of males, show a peculiarity: According to Matschei (2012) in ewes horn growth correlates with births given. Horn growth is reduced after the third year – the horns showing irregular increments. The number of such reduced increments corresponds with the number of gestations. [6] Matschei quotes Miura (1987), who worked with Japanese Serow. Since the Japanese Serow occurs at least partially in the temperate zone with distinct seasons, the horns show grooves of annual rings, which are said to be more distinct in females. [8] This poses the question of how „gestation grooves“ and „annual grooves“ merge or interfere.

glands: serows lack the skin glands of the posterior horn area of the head that are present in chamois. However there are large scent glands below the eyes. [1] Foot glands between the 3rd and 4th claws are also present. These interdigital glands presumably also serve to mark the territory. [6]

General biology

The serow’s senses of smell, vision, and hearing are acute. The alarm call is a snort or hiss. Serow are not as quick and agile as goral, nevertheless they are sure-footed, clambering easily along well defined trails on mountain slopes, even climbing cliff growing trees. They are also good swimmers. [6] Serow, expecially males, are usually solitary, but sometimes found in pairs or small family groups [1] – up to seven [6]. Serows are also known to frequent selected places for defecating. In mixed groups both sexes visit these places. [6]

Compared with Mountain Goat (Oreamnos americanus), chamois (Rupicapra rupicapa and R. pyrenaica) and goral (Nemorhaedus sp.) serow species exhibit fewer behavior patterns. The genus is considered to be behaviorally primitive. [8]

Fresh Dung of a Chinese Serow (identified by local guide – not confirmed, but plausible). Photo taken at Foping Nature Reserve, China. Diameter of ring: 2 cm. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

Serow reach sexual maturity at about three years. Rams [1] and females [6] mark their territories by rubbing a strong-smelling secretion from their prominent preorbital glands on rocks [1], branches and plants. [6] Agonistic behaviour is sometimes seen among territorial males. Since fights are often damaging, serow try to avoid direct confrontation through territory marking and the presentation of their bodies. [6]

The behavioral repertoire – which is said to be primitive – includes: head butt, butt (other than head), chase, head down (static), head up, hook, hop, horning of vegetation, kick, lip-curl, low stretch, marking, naso-genital and naso-nasal contact. [1]

Female „Assamese Red Serow“ presumably controlling a scent mark. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Guwahati Zoo, Assam

mating season: because of their huge distribution range the period for mating is not consistend. Mating season in Myanmar is in September and October, in Thailand it is October and November. In the tropics serow presumably mate year-round. [6]

gestation period: 200-230 days [1]

number of kids born: 1 [1]; rarely twins [6]

feeding: selective browsing; eating grasses, herbs, leaves, shoots, twigs of trees and shrubs [1]; forage plant species are determined by habitat. For the Japanese Serow around 100 plant species are known. [6]

„Assamese Red Serow“ being fed with banana at Guwahati Zoo, Assam, India. Most likely fruits are also an integral component of the serow’s diet. Photo: Ralf Bürglin

most active: at dawn and dusk [1, 6]

life expectancy: Matschei (2012) guesses 12-15 years in the wild; he mentions a record age of a Japanese Serow in the Zoo of Nagoya, Japan, which died with the age of 27 years, 7 month and 25 days. [6]

Habitat

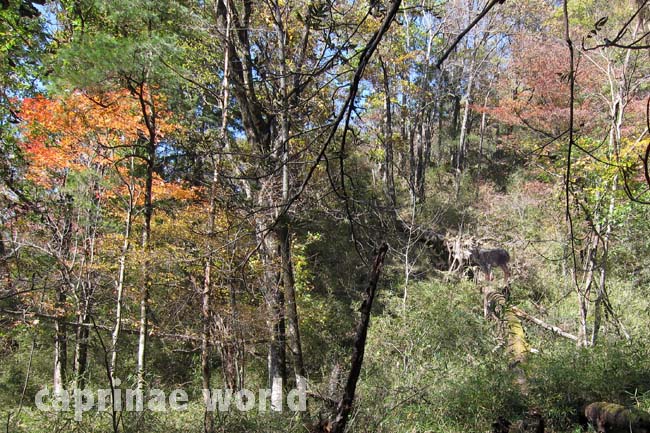

Serows prefer to roam precipitous thickly-forested slopes. [1] According to their vast distribution area, the serows habitat is diverse. Tropical species like the Sumatran Serow inhabit rocky areas within the rainforest, whereas species of more northerly areas prefer southerly exposed, grassy slopes close to Rhododendron- and Oak forests. [6] They are rarely seen in open areas. During the heat of the day, they shelter among rocks, in caves or in dense underbrush. [1] For resting serows also seek elevated places. [6]

A Chinese Serow at Foping Nature Reserve at its resting place on a fallen tree. The serow was known to use the site repeatedly. Photo-collage: Ralf Bürglin

Threats

Habitat loss and poaching for meat and medicinal use threaten almost all serow species. The unresolved serow taxonomy and an apparent lack of knowledge in phenoype distribution ranges and current population numbers, seriously impedes a more focused conservation action. [1]

A purely protectionist approach to conserving serow in the few protected areas, with law enforcement indequate to the task of preventing poaching has failed so far (in many places), and continuation of this policy will further reduce serow numbers and range. [1]

Serows and culture

Warrior’s Victory Basket (Konyak tribe, Nagaland, India) with three monkey sculls and two serow horn sheaths. Photo: Ralf Bürglin, Nagaland State Museum, Kohima, India

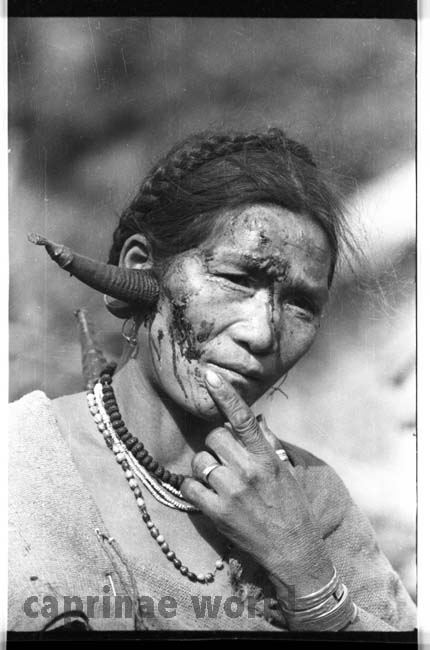

Blood-letting by means of serow horns

When the Austrian anthropologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf visited the Kiyi River valley, Arunachal Pradesh, India in 1945, he was stopped en route at the settlement of Kirum and asked for medicine by two women from the Nyishi tribe. One woman with inflamed eyes had her face covered in congealed blood; on one cheek and the back of her neck serow-horns were affixed by suctions and through these her blood had been let after incisions had been made in the skin.

Nyishi woman letting blood by means of two serow-horns – one infront of right ear, the other one on the back. Source: Digital SOAS

Trophy Hunting

Serow have not been much hunted by sport hunters, mostly because the species are little known in international hunting circles. Interest disappeared completely after serow and goral hunting was closed in Nepal and China. The few serows listed in record books appear to have been harvested as incidental quarry, or were entered onto the lists by travel-explorer hunters of bygone years. [1] Damm and Franco (2014) believe that involving the interest of rural residents in conservation through a pragmatic conservation approach, which includes hunting, will bring tangible economic benefits to the communities and their members, which will prevent them from poaching serow.

Literature cited

[1] Damm, Gerhard R. and Franco, Nicolás, 2014: The CIC Caprinae Atlas of the World – CIC International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation, Budakeszi, Hungary in cooperation with Rowland Ward Publications RSA (Pty) Ltd., Johannesburg, South Africa.

[3] Groves, Colin and Grubb, Peter, 2011: Ungulate taxonomy. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

[5] Duckworth, J.W., Steinmetz, R. & MacKinnon, J. 2008. Capricornis sumatraensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T3812A10099434. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T3812A10099434.en. Downloaded on 20 March 2017.

[6] Matschei, Christian, 2012: Böcke, Takine und Moschusochsen. Filander Verlag

[7] Mori, Emiliano; Nerva, Luca; Lovari, Sandro, 2019: Reclassification of the serows and gorals: the end of a neverending story? Mammal Review ISSN 0305-1838.

[8] Jass, Christopher N. and Mead, Jim I., 2004: Capricornis crispus. Mammalian Species, No. 750, pp. 1–10, American Society of Mammalogists

[9] Wilson, D. E. and Mittermeier, R. A. [eds], 2011: Handbook of the mammals of the world. Vol. 2. Hoofed mammals. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.